Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 2

Above is a global view giving an idea of the distance between Hamburg, our last port of call and the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands - our next destination. The map below shows the relative proximity of Cape Verde's "nextdoor neighbors".

The weather had warmed up considerably to say the least by the time we reached the Cape Verde islands. The only reason that we stopped there as far as I can remember was so that the Captain could replenish his favourite "plonk" which was, guess what? Yes, the famous Vino Verde wine (which would have cost a fortune in the UK and probably still does).

I remember we dropped anchor early on a sunny afternoon. It didn't take long for a launch to approach from which case upon case of the wine was carried up the gangway by our Lascar crew to dissappear forever from our sight. We lifted the anchor and continued on our way as the sun went down in a glorious blaze behind the islands.

Below is a photo of Cabo Verde's Sao Vicente Beach as it is today . The island that we dropped anchor at was covered in jungle and looked nothing like this .

Next stop? Durban, South Africa.

If you have been wondering why , since we were sailing to Karachi in West Pakistan (as it was at the time called) we didn't take the direct route through the Suez Canal, it is simply that we couldn't - it was blocked!

The year before in 1967 I was aboard an oil tanker underway to the Persian Gulf. We were in the Mediterranean only two days from Suez - it was night time and I was on watch in the radio room when the 3rd Mate (who had the 0800 - 1200 watch) came crashing in a panic into the room. He was shouting something like "come quick, they're flashing at us too fast" and then ran back into the wheelhouse. I got up and followed him onto the bridge . He had the Aldis signalling lamp in his hand and was pointing astern shouting "Sparks, what are they saying?". I looked astern but couldn't see anything much because from coming out of the brightly lit radio room into the dark I had lost my night vision and it would take about five minutes before I regained it. The 3rd Mate was still dancing around agitated and by the time I could start to see it was too late. The American 6th fleet had come up behind us (and had been signalling us to get the f... out of their way) and now we were right in the middle of it. I remember staring up at the dark shadow of a massive aircraft carrier pounding its way past us - all of the fleet's ships were "blacked out" not even showing navigation lights.

The "6 Day" Arab-Israeli war had just broken out and the US fleet was galloping as fast as it could to get as close as it could. We heard the first news bulletin about it the next day on the radio.

We were by now all thinking "what are we going to do now?". We sent a radio telegram to our tanker company asking the same question but continued on our way. The day before we would have reached Suez I got a reply which told us to turn around and head back the way we came and await further orders. A few days later when we were almost passing Gibralter we got orders to proceed to Lisbon, Portugal.

What heaven, what bliss! Instead of the dreaded Persian Gulf, the lovely Lisbon instead. We tied up at a very small oil wharf just diagonally across the Tigris River from the heart of Lisbon and stayed there seven days. This was before mass tourism could ruin a country. It was here that I fell in love with Fado (not Fido!) music, amongst other things.

All good things come to an end as we then got orders to proceed to Bonny, Nigeria and believe me there was nothing bonny about the place (when we got there the civil war between the Nigerian Govnmt. and the Ibo's was in full swing and I spent days on end with little sleep transmitting messages concerning Shell Oil assets and their workers and other European/US refugees) but that's another story.

The days pass by filled with shipboard routine - my watches were "two hours on, two hours off" and many a time if I was too busy in the "on watch" period I would just continue work into the next. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the crew were apart from the Officers all "Lascars" - Indian seamen. There were at least 50 of them aboard and they all had their quarters in the aft of the vessel (aboard the last two vessels I had sailed on the crew were also Lascar). Although the Weybank was registered in Glasgow, which was painted below "Weybank" on the stern - for the next year we could have had Glasgow painted over with Calcutta (or Kolkata as it is now called) instead as it became practically our home port. To understand the conditions in which they lived and worked aboard it is neccessary here to include a short "history":

A Lascar was originally a sailor or militiaman from South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Arab world, and other territories located to the east of the Cape of Good Hope, who were employed on European ships from the 16th century until the middle of the 20th century.

The word (also spelled lashkar, Alaskar) derives from al-askar, the Arabic word for a guard or soldier. The Portuguese adapted this term to "lascarim", meaning an Asian militiamen or seamen, specifically from any area East of the Cape of Good Hope. This means that Indian, Malay, Chinese and Japanese crewmen were covered by the Portuguese definition. The British of the East India Company initially described Indian lascars as 'Black Portuguese' or 'Topazes', but later adopted the Portuguese name, calling them 'Lascar'. Lascars served on British ships under "lascar agreements." These agreements allowed shipowners more control than was the case in ordinary articles of agreement. The sailors could be transferred from one ship to another and retained in service for up to three years at one time. The name Lascar was also used to refer to Indian servants, typically engaged by British military officers.

At the beginning of World War I, there were 51,616 Lascars working on British merchant ships in and around the British Empire.

In World War II thousands of Lascars served in the war and died on vessels throughout the World, especially those of the British India Steam Navigation Company, P&O and other British shipping companies. The term “Lascar” is not in use today, but as a period term it identified men who were engaged at ports in India under the special terms of a running Agreement. The Lascar Agreement replaced the standard foreign-going Agreement (Eng 1) for seafarers of Indian, African and Middle-Eastern origin. Its intention was that men on voyages between ports in the Indian Ocean and ports in the UK or near-continental Europe would return to Bombay (Mumbai) or Calcutta (Kolkata) or another Asian port where they could again be recruited as shipboard labour. The terms to which they agreed differentiated them from European seafarers, often working aboard the same vessels.

A diet of rice, flour, dhall, ghee, curry stuffs, dried fish, vegetables, and a little meat deferred to Lascar cultural preferences and religious practices. These comestibles were cheaper for the shipowner to provide than the standard seafaring fare. Less space aboard was allotted to Lascar crew, though the most important saving on Lascars recruited to trans-oceanic vessels came from lower wages. The Indian Government’s Merchant Shipping Act of 1880 authorized pay amounting to half that for British seafarers. The rate was justified by the lower remuneration to workers in India.

Native “bosses” known as serangs and tindals, took the place of bo’sns (boatswains) in organizing Lascar teams for shipboard work and in-port labour. Lascars continued to work after their vessels arrived in port. Officers had even less to do with Lascars. Their customary authority was buttressed by the advantages they drew from being white men aboard the ships of an empire whose non-white subjects had rights but of a kind that were ambiguous and debated.

Among the companies making extensive use of Lascar labour were the Peninsular and Oriental [P&O] operating from London, and the British India Steam Navigation [BISN], that made Glasgow its base. The separate Agreement for Indian seafarers predated the formation of these enterprises by many years. Its origins are with the East India Company, which operated under a charter granted by the state until its monopoly on Indian trade was revoked in the first half of the nineteenth century. The employment of Lascars accelerated once the Suez Canal (1869) shortened the voyage to the East and gave merchants to reconsider the merits of shipping by steam or sail since steamships alone could use the canal. P&O led in the renewal of its fleet. It commissioned ships with compound steam engines and screw propellers and put more Lascars into the stokeholds of these vessels.

The companies involved provided justification for the increased use of Lascars. They argued that Europeans were not suited to work in hot climates: the temperatures in the stokeholds of a steam vessel could exceed 100°F (38°C). In addition, they parried criticism that cheapness was the reason for the use of Asian labour. Businesses and their representatives said the cheaper costs of the Lascar seafarer to his employer were evened out because two Lascars were needed in place of every European.

In the middle of the nineteenth century the laws were repealed that had been passed in previous centuries with the intention that crews on British vessels should be constituted by a majority of British or Colonial born seafarers. The status of Lascars was left ambiguous under both British and Colonial laws, though it might truer to say that as Lascar numbers increased some commentators began to assert that Lascars had never been British seamen, and thus they could not benefit from the protection that British mercantile marine law routinely provided its subjects (Merchant Shipping Act 1850). In 1903 a polemicist, Captain W.H. Hood, took an optimistically xenophobic view of the matter: “The conditions of life in our service were much better than any other service in the world. As a consequence, foreigners were always glad to join our ships”.

Imperialists in both conservative and liberal political camps were on dicey ground when perceptions of developmental differences between east and west left the Lascar looking only half a man as compared with a European. What might happen to shipping services to the East should military service take European officers, members of the Royal Naval Reserves, away from their regular duties? Hood was one of the authors who, after the Boer war, went into print to defend the fortitude and moral courage of Lascars. Another factor played into the hands of these new defenders of the Lascar. Over the previous decade strikes at British ports showed the strengthening of support for a neophyte trade union (Marsh 1989). Hood characterized the new mood of seafarer militancy in a telling way: he called it “The Blight of Insubordination”. The National Seamen’s and Firemen’s Union could not overlook the existence of British-registered vessels putting in to British ports that were manned by seafarers who worked for lower pay and in inferior conditions.

In 1940, in the period of decolonization, Labour minister Ernest Bevin protested the term with passion [he], “would not allow them to be called Lascars any more. They are Indian seamen, and when you get rid of the term Lascar, you will rid of the conception that they are cheap human fodder.” It was 1953, however, before sensitivities to the differentiation of “Indian seamen” by race prevailed and they became “Seaman Class I and Class II”.

Lascar Glossary

Serang - Boatswain

Ghat Serang - Lascar agent for the supply of labour

Tindal - Boatswain’s mate

Seacunny - Quartermaster

Topass - Ordinary-seaman

Bhandary - Forecastle cook

Fireman’s Serang - Donkeyman

Paniwalla - Greaser

Lampman - Storekeeper and lamps

Fireman - Fireman

Trimmer - Trimmer

Dhobiwalla - Laundryman

Above is a glossary of Lascar ranks but it is no means complete. During my time aboard I myself had little contact with most of them. One reason for this was that being the R/O I was in the unique position of working mainly by myself and I was not employed by Andrew Weir - The Bank Line, but by Marconi Marine who "hired out" their R/O's and radio equipment to the shipping companies.

The crew of a vessel works either for the Deck dept., The Engineering dept., or the Radio Dept. and in some cases the Stewards Dept.

Aboard the Weybank the Deck Officers are the 1st Mate, 2nd Mate and 3rd Mate and two Officer Cadets called Apprentices.

The Engineering Officers are the Chief Engineer, 2nd Eng., 3rd Eng., 4th Eng., 5th Eng and 6th Eng. The 1st and 2nd Electricians were also under the command of the Chief Engineer. There was also a Chief Steward and the Radio Officer (R/O) (myself).

Aboard any ship there is a kind of hierarchy (in the minds of many a deck officer) which stems from the age of sail according to the motto "We got along just fine without an engine or radio/radar and also we were here first!". For this reason good-natured

"slagging" as the Irish would say takes place between the Deck and Engine departments - "You couldn't get anywhere without us - you are just glorified bus conducters" reply the engineers.

In some cases the banter was not so friendly - I was once sitting in the Officers Mess (or Dayroom/Saloon) with some other officers when the 1st Mate came in in a bad mood. He started an argument with us in which his pressure cooker was starting to steam when he suddenly shouted "I am the Chief Officer!", probably in the hope of asserting some kind of authority. I replied that this could not be as I, being the only officer aboard must surely deserve the title of "Chief".

This was true because when signing the articles when joining a British ship the captain signs on as Master, the deck "officers" as 1st Mate, 2nd Mate etc., and the engineering "officers" as Chief Eng., 2nd Eng. etc.

The other hierarchical issues which affected me were for instance that since the Radio dept. was an autonomous dept. as were the Deck & Engineering depts., I was entitled to sit at the Captain's Table at meal times with the 1st Mate and Chief Engineer. If the captain didn't like me then I was entitled to have a table to myself in the Dining Saloon. I also shared the Captain's Steward who looked after only the Captain's and my own cabin. The Lascar rank for this position was "Captain's Boy".

The greatest thing for me was that I was answerable only to the Captain - no one else could order me around.

Returning to the Lascars aboard ( I use the term with respect for these seamen - instead of saying "Indian seamen" all the time) another reason for the little contact with them was the language barrier - they spoke Urdu or Hindi or one of the many other Indian languages but very little or no English. They were told what to do by their own bosses - the Serangs and Tindals and when not on duty lived in their own world at the stern of the vessel .

I had a great pity for most of the Lascars - they joined the ship in Calcutta but to get signed-on in the first place they had to pay "Baksheesh" to the Ghat Serang - the Lascars Labour Agent. The first time I myself realised what real poverty meant was when, only 8 years old, I was in Bombay (or Mumbai as it is now called). Calcutta in my opinion was even worse - the port teeming with the destitute - horrible poverty. That was probably why the Lascars were happy to be aboard.

Amongst them aboard, the Indian Caste system also played a role. Every morning at sea a frail old man, bare footed and wearing a shirt and short trousers that were almost rags knocked timidly on the radio room door. Although each time I shouted "Come In" he never did unless I got up from my seat and opened the door myself. He always, bowing low and repeatedly uttering "Sahib" timidly entered the radio room with his brush and dust-pan and started to sweep the floor but like a frightened bird trying to escape his cage. Due to the language barrier I could not converse with him but each time before he left I gave him a packet of cigarettes or some Rupees if I had any left . He was always almost too scared to take it, his outstreched arm and hand shaking like an Aspen leaf in a storm. In the three months in which he was aboard before the crew was once again changed in Calcutta, this scene repeated itself without change day by day.

Returning to our voyage, we are approaching the southern tip of Africa.

The basic map shown above was drawn in the "Mercator Projection" but does not show any lines of latitude (apart from the Equator) or longitude. The dashed line drawn acoss it just below the middle represents the Equator (which is 0° latitude). This kind of map makes sense to us all - we know through education that Japan is for instance a long way from the United Kingdom and looking at the map confirms our knowledge but If someone showed me this same map and asked "how far is it from where it is written "South Africa" to where it is written "France", I wouldn't have a clue - unless the lines of latitude had been drawn across the map!!

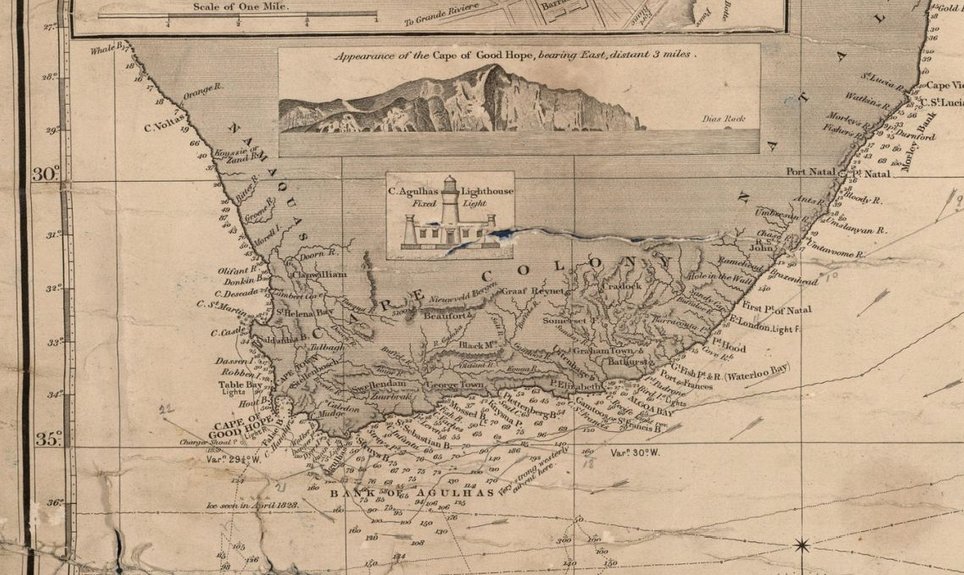

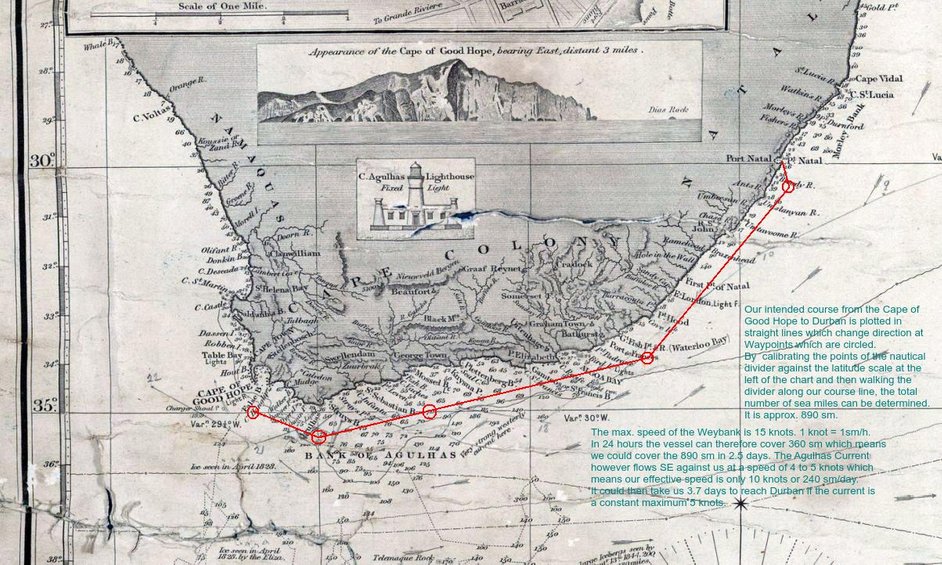

Below is an excerpt from an Ocean Chart from 1870 which is to date 146 years old!

In the 146 years since the chart was made many things have of course changed but these are basically name changes of towns, cities and states. The coast lines have not changed significantly and the sea itself only invisibly - pollution and ocean warming - fish mercilessly trawled by huge fishing fleets accompanied by fish-factory processing vessels - sharks "culled" for their fins, often thrown back alive in the sea.

Viewing this 1870's chart is also a history lesson. 146 years may sound like a millenium to a youngster but to me it is only just over twice my age. Capetown on the chart is still Capetown today. Port Elizabeth likewise. Port Natal however is now called Durban,

Namaquas is now Namibia etc.

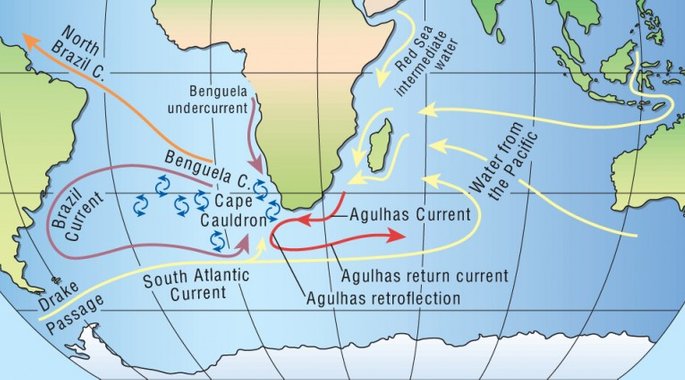

The elongated arrows on the chart represent the direction of current flow. The Agulhas Current is the strongest western boundary current in the world’s oceans. It flows along the eastern side of southern Africa, and when it reaches the tip of Africa, it is “retroflected” to flow east, parallel to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. It has an average speed of 4-5 knots (nautical miles per hour). You can see the arrows on the chart running down the length of the coast.

You often read or hear of "wind-jammers" - clipper ships or three or four-masted barques rounding the Cape (the Cape of Good Hope)

but if they really did this they would end up in False Bay and soon run aground. The lowest point in the African continent is Agulhas (after which the current is named). From Agulhas, if you now continue to sail along the coast, you are sailing northwards.

At the time the 1870 chart was drawn there was a lighthouse sited at Agulhas which emitted a continuous (fixed) white light and a picture of this lighthouse is drawn on the chart - so important was it for navigators who could take visual bearings of it during daytime and at night from its light. The Cape of Good Hope had only in comparison a red light at the time. Today the Cape has a lighthouse and Agulhas a beacon.

The chart was compiled purely from the cumulative observations made by seamen and land cartographers through the past decades and centuries . It was drawn without the aid of photography from aircraft (aircraft didn't exist at the time) and you know yourselves when the Sputnik was launched. It is amazing how accurate such charts were.

Not only has satellite technology enabled precise contoured modern sea charts to be drawn , it has also produced GPS - the Global Positioning System which enables a navigator to pinpoint his ship's position. There are all kinds of electronic chart plotting "state of the art" equipment carried aboard merchant vessels these days, all in one way or another linked with GPS whose consoles display charts with all the "bells & whistles". However, there is nothing to beat using also a conventional sea chart and as far as I know on British ships it is still compulsory to carry them aboard and keep them updated.

The chart above is a Mercator projection which includes a grid calibrated in lines of latitude and longitude which basically means that we can use it as a kind of "street map" to find our way about. ("Google" for instance uses the same Mercator projection method with a few technological "perks" added but without Lat. & Long. calibration displayed).

If you look to the left you will see a scale calibrated in degrees. At the point marked 30°, a horizontal line runs right across the chart . This is called a line of latitude (the lines running verticaly are lines of longitude). Further below at 35° runs another horizontal latitude line. Between these two lines the scale is calibrated in major steps of one degree, i.e. 30°, 31°, 32°, 33° 34°, 35°.

Each degree in latitude represents a distance of 60 Nautical Miles (nm) therefore the distance between 30° and 35° latitude on the chart is 300 Nautical Miles.

5° = 300 Nautical Miles = 555.6 Km.

1° = 60 Nautical Miles = 111.12 Km.

One single degree consists of 60 "Minutes" of latitude.

One "Minute" represents a distance of one Nautical Mile (1 nm).

1 nm = 6000 ft. (or 6076 ft. by international treaties).

1 nm = 2000 yards (or 1760 yards/Statute Mile)

1 nm = 1852 meters)

The vertical scale on the left side of the chart, calibrated in degrees, pertains to the horizontal lines of latitude and it is this scale which is used by a navigator to determine distance on the chart. A sea chart has a horizontal scale at the top of the chart also calibrated in degrees but pertains to the vertical longitudinal lines running down the chart and is NOT used to determine distance.

How can one put this knowledge into practical use? With the aid of a simple instrument called a "divider", the function of which is explained below.

Chart Divider

How to use dividers

Using dividers and the latitude scale on your nautical chart, you are able to measure distance in nautical miles. (Remember, do not use longitudes to measure distance. Longitude lines converge at the poles and the distance between them changes relative to your position on the earth.)

One minute equals one nautical mile; one degree equals 60 nautical miles. Examine the scale of your chart. In these examples, our chart is in degrees and minutes.

Place one point of the dividers at position A and the other point at at position B. Then, maintaining the spread, measure the distance using the latitude scale. In this case, the distance is 15 minutes or 15 nautical miles. Always use the latitude scale located in the same horizontal region that you are measuring.

Walking the dividers enables you to measure distances greater than the span of your divider.

You can either draw the line or use a straight edge to guide the dividers.

To measure, set the dividers to a whole number on the latitude scale, in this case we use 12 (=12 minutes), and then from the starting position walk the dividers along the line. Because 1 Minute also equals 1 sea mile and we set the divider's span to 12, with three "steps" we have measured 36 nm. We have however still not measured the complete line to its end point but you will soon see how to accomplish this.

The distance between the two buoys below is 24 nautical miles (two steps of 12 miles each). But it seldom works out so evenly.

In an other and final example below between two different buoys we adjust the last step of the dividers, measure the distance, and add it to the cumulative total of previous steps. We only had one previous step in this example so the distance measured is 12 plus 7.75=19.75 sea miles.

We can now put this knowledge to practical use using the same 1870's chart:

If you look at the bottom of the chart above you can see the Agulhas Current arrows pointing in an easterly direction.

Also note the text concerning the Agulhas westerly flow near the coast "Very strong westerly current here" and also the comments concerning ice and icebergs which have floated up from the Antarctic. The position of "Ice seen in April 1828" is only about 120 sm south of the Cape of Good Hope!.

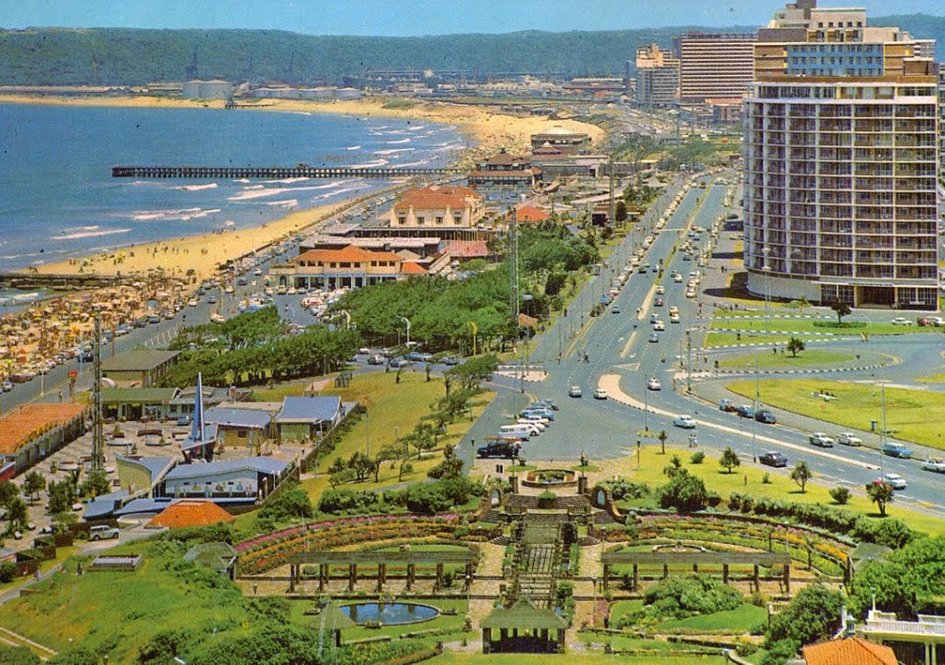

We finally arrived at Durban in the evening but none of us could go ashore as we were only bunkering (navy-speak for refuelling pit-stop) at some remote bunker station and continued on our way to Karachi as the sun went up. However , we would return in the future to Durban frequently to charge/discharge cargo and so at this point I will show you what you are missing!

The photo above, taken in 1968, shows just some of the Durban beaches .

A view of a Durban beach in 2016

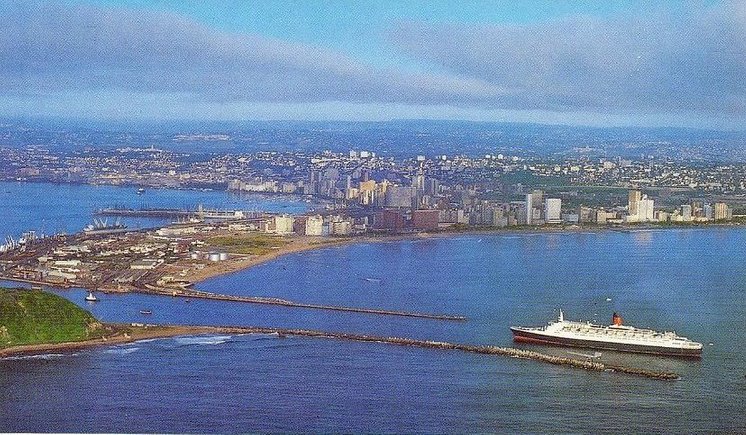

The Cunard liner QE2 entering Durban harbour through the breakwater channel.

Durban (Zulu, meaning "bay/lagoon") is the largest city in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal and is the third largest city in South Africa after Johannesburg and Cape Town. It is also the busiest port in SA. It is also a "tourist trap" because of its subtropical climate and extensive beaches.

The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, who sailed parallel to the KwaZulu-Natal coast at Christmastide in 1497 while searching for a route from Europe to India, named the area "Natal", which means Christmas in Portuguese and also explains such names as Agulhas.

Like all things in life there is a "Ying and Jang" , a positive and negative side and unfortunately this also applies to the beautiful beaches - "all that glitters is not gold", for example:

Black December refers to at least nine shark attacks on humans causing six deaths that occurred along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, from December 18, 1957 to April 5, 1958.

In December 1957 several key factors occurred simultaneously to attract sharks to the Durban area, including: whaling ships operating in the area; rivers had flooded and washed livestock into the Indian Ocean and made the river deltas murky; and recent resort development had increased the number of tourists swimming off the beaches. Adding to the confusion was the lack of adequate shark research and the knowledge to prevent shark attacks in 1957.

Tourists fled the Durban area during Black December causing a devastating impact on the local economy. The local authorities desperately made attempts to protect swimmers and surfers from sharks. These attempts included enclosures built from wooden poles and netting; however, both were ineffective and were destroyed by the surf. A South African Navy frigate dropped depth charges causing few shark fatalities and attracted many more sharks into the area that feasted on the dead fish.

As a result of Black December the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board (previously the Natal Sharks Board and Natal Anti-Shark Measures Board) was formed in 1962. The organizations mandate is to maintain shark nets and drum lines at 38 places, along 320 km of coastline off the KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, to protect bathers and surfers from shark attacks.

Today in 2016, there is controversy surrounding the KwaZulu Natal Sharks Board i.e., protecting swimmers or culling sharks?

Just in case you've never seen one, here is what a Great White Shark looks like up close:

Durban is home to another species of shark which is not the Great White or Hammerhead - I would (more than) happily swim over the shark net to plunge amongst them:

Cheerleaders of the Durban Sharks rugby team.

Farewell you beautiful sharks, alas we must depart - destiny is calling. King Solomon's Mines, Rudyard Kipling, Omar Khayyam and seductively lounging Indian princesses have long since fired our imaginations. Karachi beckons, we cannot resist (even if we wanted to).