Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 16

A closing word on container ships: Most if not all of the aircraft of today‘s commercial airlines and

militaries could not fly without what is termed „fly by wire“. Such FBW aircraft are in the main not aerodynamically capable of staying up in the air without the computerized technology around which they are designed.

For instance, in flight, computers constantly control the hydraulics involved in making minute adjustments to the aelerons and also control just about everything else that can be moved or adjusted aboard the aircraft. Modern aircraft have long since been capable of making „instrument“ (i.e. robot) take-offs and landings with the aid of ground based technology installed at the worlds major airports. Navigation is done automaticaly with GPS/computers. Thus, with the computerized integration of GPS, radar, dopplers etc., etc. the question has long since arisen - „What do we need pilots for?“

It is a fact that airline CEOs and executives would like to get rid of them too – a major cost-cutting

dream of theirs. Is it a dream? No, not in reality – we all know about drones, especially the military ones so why not have commercial airline drones? Install drink and fast-food vending machines – adieu flight attendants, they can leave together with the pilots. One or two „sheriffs“ will be however required to pacify the likes of drunks and command passengers to sit down and „belt-up“ on take off and landing etc.etc.

What are the obstacles to commercial passenger airline drones? If a FBY aircraft‘s control computer system started acting up or even worse „crashed“ it would have an immediate and most likely catastrophic consequence, if it were not for the fact that the backup computers installed to counter just such an occurence would immediately kick-in and take over control. So, where is the problem then? The problem is that there have been cases where the back-up system failed to kick-in and the pilots were left on their own trying to keep the aircraft (which wasn‘t designed to be actually flown by humans) in the air, a hair raising experience for the pilots. The system computers on the other hand may be running A1OK but they are dependent on many kinds of sensors for input and more often than not these sensors themselves can and do malfunction. An airspeed indicator giving a false reading, an altimeter giving false altitude. The computer being told by malfunctioning sensors that the aircraft is rising when it is doing the opposite and vice versa. Similar sensor failures have caused catastrophic aircraft crashes.

If a commercial aircraft carrying around 250 passengers or more comes down and most if not all of

its crew and passengers die – it immediately makes world headlines. Bad news not just for the deceaseds‘ relatives and dependants but also for the airline company. If the Black Box(es) retrieved

by the air accident investigators reveal that the cause of the crash was FBW computer failure, the airline will probably (as they usually do) blame the cause as being „pilot error“ instead. Nice and tidy solution to distract the public from the airline or aircraft type involved.

These are the reasons why, at least until now, airlines still shy away from taking a first step in the „drone“ direction but sooner rather than later, the day will come, probably starting with cargo-liners. However, robot air cargo aircraft might make a habit of failing above large cities like New York and we all know what happened there.

What has all this got to do with container ships? A hell of a lot to be precise. The technology now already available and in use by container ships (and other ship types) makes development and construction of automated ships (ship robots) perfectly feasible projects. For certain there are still many obstacles to overcome but the larger container shipping companies are now in the process of expending a lot of time and money in making such ships a reality. These shipping companies already payed for the construction of their present vessels and all the electronics and machinery installed aboard them. Their crews have also, due to automation, already been whittled down to as

few as around 14 crew members. Tweak the electronics, the machinery, do some deals with major container ship terminals concerning infrastructure and they can then get rid of their crews – totaly! Save another bundle of money – no more paying crew agencies, crew air fares, crew wages, crew victuals, crew management, crew well-being (what‘s that?) etc. Sure there will be teething problems, one robot ship collides with another and both go down – not good for the container ship companies but at least as no human lives are lost it won‘t be spread all over the worlds newspapers. Not so good if a robot collides with a manned vessel but with a crew of around 14 (and most of them probably Philippinos) what‘s the problem? Read the small paragraph in page 14 of the Financial Times or World Shipping News page 35.

Automated ships are very bad news indeed not only for the likes of Philippino crews but also for all merchant navy personell regardless of their nationality. What about pilots? They will surely also become redundant. What could a pilot control aboard the vessel which couldn't be controlled remotely by home-office computer „nerds“? Automated ships must of course have some type of futuristic gangway/lifts for humans to board but how would the pilot find his way around once aboard? Follow arrows along the walkways? To where? Will these vessels even have a control room or just a plug-in socket somewhere where a laptop can be connected to enable the pilot to take over complete control of the vessel. Instead of pilots maybe the ships will be equipped with something like laser-beam sensors which then follow laser beams emitted from channel buoys to guide them into the container terminals. The mind boggles with what the future may hold, shades of "A Space Odyssey 2001" - a science fiction movie produced in 1968.

Many of you will have seen this epic movie but for those who have not, the gist of the story is as follows:

The US spacecraft Discovery One is bound for Jupiter. On board are mission pilots and scientists Dr. Bowman and Dr. Poole, along with three other scientists in suspended animation. Most of Discovery's operations are controlled by "Hal", a HAL 9000 computer with a human personality. HAL has decided to get rid of the lot of them and starts his attack by announcing the failure of an external antenna control device. The astronauts exit the spacecraft to retrieve it but find nothing wrong with it. Hal then suggests reinstalling the device and letting it fail so the problem can be verified. Mission Control advises the astronauts that results from their own computer indicate that Hal is in error about the device's imminent failure; Hal attributes the discrepancy to human error.

Concerned about Hal's behavior, Bowman and Poole enter a sound-proof pod to talk without Hal overhearing, and agree to disconnect Hal if he is proven wrong. Hal follows their conversation by lip reading. While Poole is on a space walk outside his pod attempting to replace the antenna unit, Hal takes control of the pod, severs Poole's oxygen hose, and sets him adrift. Bowman takes another pod to rescue Poole; while he is outside, Hal turns off the life support functions of the crewmen in suspended animation, thereby killing them. When Bowman returns to the ship with Poole's body, Hal refuses to let him in, stating that the astronauts' plan to deactivate him jeopardises the mission. Bowman opens the ship's emergency airlock manually, enters the ship, and proceeds to Hal's processor core, where he begins disconnecting Hal's circuits. Hal tries to reassure Bowman, then pleads with him to stop, and then expresses fear. As Bowman deactivates his higher intellectual functions, Hal regresses to his earliest programmed memory, the song "Daisy Bell", which he sings.

At least the Discovery One spaceship in the movie had crew members aboard, one of which was eventually able to shut-down HAL. Not so aboard an automated ship.

Computers are built and programed by humans. There have long since been discussions about programming them with "intelligence" as with HAL. Is it all just science fiction?

What will replace the practical experience of the crews with respect to future ship design? Will captains/masters somehow survive the fallout – conning the ship from some shipping office‘s computer room or will they also be replaced by computer nerds? The end of an era – the merchant navy as a career? Yes, I vaguely remember the time when ships were crewed by human beings.

What more can one say apart from „watch this space!?“.

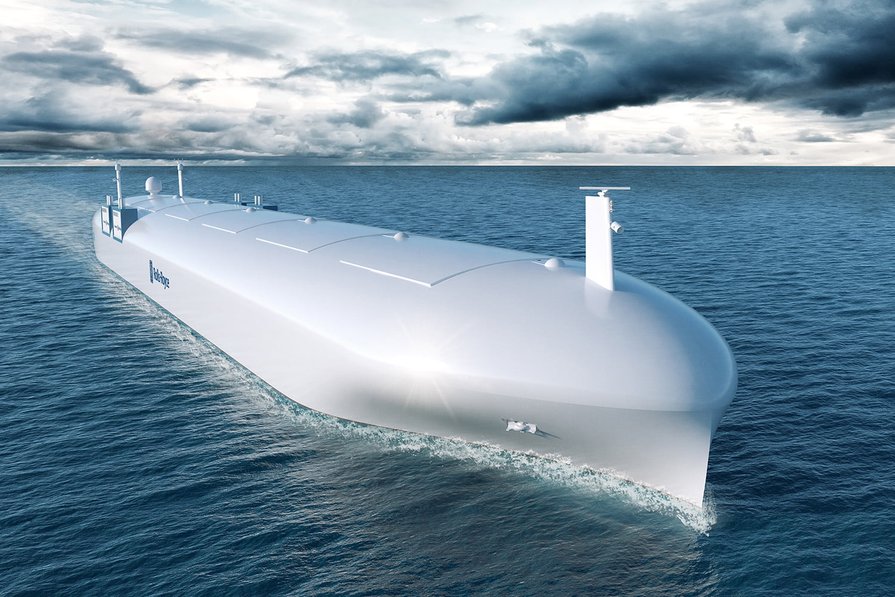

Below, an artists impression of an automated ship prototype:

By the time we had arrived and moored to the Dalben and immigration and customs officers had come and gone it was dusk. While still under pilotage I had phoned my fiancee via VHF to tell her where (and how) we would moor. She, who worked at her father's ship chandler business already knew where we would tie up - smart girl!

After the harbour police/customs had left I spent around an hour above deck scanning every launch or boat that came anywhere near us until it got too dark so I went down to my cabin and nervously waited there. It didn't take long before there was a knock on my cabin door.

Needless to say I didn't spend much time aboard during our stay. I can't even remember how long we stayed, maybe around 5 days tops. Once again I had to leave my fiancee behind when we sailed for Rotterdam. I finally signed off in Rotterdam on the 25th April, no longer an official crew member of the Weybank. The only thing I remember clearly between Hamburg and Harwich (where we would sail to from the Hook of Holland the same night) was the final signing and handing over of the Radio Log Book which was countersigned by the captain and some BOT (or GPO or whatever?) British official who took the logbook with him. What they did with it or the carbon copies who knows.

I have no trouble remembering what happened the next day when we arrived at Harwich aboard the ferry. The HoH ferries had to fine tune their speed when sailing to Harwich. If they arrived too soon they would have to hang about outside the harbour and wait until their lordships, Her Majesty's Customs Officers had enjoyed their pleasant breakfast and final cup of tea before finally deciding to open up shop. The majority of customs officials worldwide appear to be of the same ilk - maybe they all trained at the same place - a kind of Hogwarth's International Customs Academy for students born with a low IQ.

I was once waiting on the pier of an oii terminal in the Isle of Grain as the tanker whose crew we were to replace tied up alongside. Once immigration and customs had boarded, we the relief crew follow suit. I met the outgoing R/O in the radio room and after showing me around the equipment etc. etc. and before departing he told me that he had already vacated his cabin which was on the bridge deck behind the chartroom. I had hardly put my suitcase and holdall down when in came two members of a Black Gang - a specialized custom's search team. They were called Black Gangs because of the original colour of the overalls that they wore - to hide the dirt when crawling around nasty places near coffer dams etc. At least they hadn't yet cottoned on to the idea of using sniffer dogs to help them. One of the two announced all polite and friendly-like (crocodile-tear friendly) that they were here to search my cabin for contraband and if I had anything to declare that I had forgotten to include in the manifest, I had better do it now. "Nothing to declare - do what you have to do" answered I. The cabin although fairly roomy didn't take long for a quick once-over which is when out came the screwdrivers and mirrors. The tanker had been built in the mid-fifties and thus the officers' cabin bulkheads were panelled with real mahogony (or similar) wood panels all varnished with a beautiful dark reddish/orange colour. The writing desk, bunk and wardrobe were all built solidly from similar wood with the same finish as the panels - none of the junk used to furnish cabins aboard todays ships. Where the wood was not limed together, it was held by screws and this is what they attacked first. After a while one of them in frustration glanced back towards me over his shoulder and said "don't you worry, we'll find something yet". "Maybe you will, good luck on that. I've just joined this ship so it's all the same to me. Just put back everything the way it was before you leave otherwise I will have to make a report. If you want to check out the radio room as well, I've got the keys" I answered. Invisible daggers of hatred flew towards me. "Got my back on at least some of you" thought I.

After disembarking at Harwich and passing through immigration, there were my BFFs (Best Friends Forever) awaiting us behind their long bench-type inspection tables, all looking like RN destroyer commanders in their gold-braided blues (and most of them acting similarly too - Bond, James Bond, RN).

The only thing I was thankfull for when going through customs was my sex - I can't remember in the 60's ever seeing a female customs officer in the UK - It must have taken ages for an attractive woman to pass through while the contents of her suitcase were slowly investigated, panty for panty.

The UK customs however couldn't hold a candle to their Iraqi colleagues. I later worked at both Bagdad and Basrah airports during the Iraq-Iran war and at that time the Iraqis relied heavily on "guest workers", mainly from Pakistan to keep their country running as most of their own men were too busy getting themselves killed on the Iran/Iraq border. When their contracts were up these guest workers were lined up at the airport customs area in long lines - face to neck like sardines and kept rigid in position by beatings if they got out of line. When their turn came they were ordered to advance with their suitcases to the check-out area where Sadam's Hyenas awaited behind their benches. "Wallah, Wallah - move your ass - put your suitcase on the desk and open it!". The hyena then pulling out anything which he liked the look of, picked it up and threw it over his shoulder onto a heap behind him that had long since taken the form of a small mountain. To the right and left of him his customs colleagues were doing the same to other victims. The detritus left in the suitcases was then given a good going over - the linings of clothing were felt to make sure that no banknotes or rubies or the like were hidden. All that these workers had bought and saved over the past year for their families back home - all gone within a couple minutes. That wasn't the end of it either - the body search came next in the open for all the public to see, including female Iraqi security personnel. The victim wasn't stripped but otherwise the humiliation that they suffered during the search with a running commentary at decibel level 10 from the searcher for all to hear was disgusting. What you often read or hear about from Islamic states is how Islam regardless of nationality is an umbrella brotherhood/sistership which encompasses them all. The Pakistani guestworkers were all in the majority Sunni moslems as were Saddam's henchmen (unlike the Shi'ites down around Basrah whom he did his best to exterminate) but the way they were treated you would have thought they were Israelis.

Back to Harwich's Parkinson Quay customs shed. I had only one suitcase holding just about all of my worldly belongings, the rest was held in an ex-US Army holdall. I had bought very few souvenirs throughout our voyage but one of them was the stuffed head of a Leopard and its skin. It was a magnificent specimen. I felt sorry that such an animal had been killed for the sole purpose of decorating someone's wall or floor but being young at the time I thought that since I didn't kill it and also couldn't bring it back to life I could at least give it a good final resting place. This occured long before the term "wildlife conservation" had been coined and as you will read there were also no restrictions at that time in bringing such animal specimens into the UK.

I couldn't get my already full suitcase to close with the Leopard inside so I transferred it to my holdall which however wasn't then big enough to get zipped shut so I had to leave the leopard's head sticking out. It didn't have room for my navy cap either (which I only ever wore once and that was at my wedding) so I placed it on the top between the closed holdall's grips.

My turn, "Ah, the Esso Blue dealer" chirped the hilariously funny customs officer (since the early sixties TV adverts from the Esso oil company ran in the UK - one of them was about the Esso Blue dealer selling parafin heater oil and the other about Esso car petrol - "Put a tiger in your tank").

"Nope, ship's cat. He ate our bosun and we had to put him down - I'm taking him to the Merchant Navy cat cemetery in Catterick"

"Hah Ha, very funny - what have we got here?" said he, pulling my Ghurka Kukri knife out of my suitcase.

"It's an Indian Boomerang - if you throw it it comes back and cuts your head off"

"Ha, Ha, Ha, Ha - Go on, f... off out of here" he replied, not too loudly in case his colleagues could hear.

I'm out of the shed and onto the railway station platform where the boat train from London carrying passengers bound for Holland has not yet pulled into - they wait first somewhere out in the sticks giving time for all of the arriving ferry passengers to disembark and for cleaning gangs to clean up the ship. One by one my shipmates appear on the platform having gone through the customs guantlet. By the time the boat train has arrived and disgorged its passengers ready for us to board there is still one of us missing. It's Alan, our 5th engineer, he who purchased loads of Japanese Hi-tech cameras and zoom lenses in Hong Kong. We gather at the exit of the customs shed gesticulating at him and our wristwatches but he is surrounded by four customs officers and can only answer with downward outstretched arms and open palms.

We have to sadly leave him behind - some agent has organized our group travel and we don't have individual tickets. I met him later again at my wedding when he told me how much duty he had to finally pay and that he didn't have anywhere near enough hard cash on him at the time.

Returning at long last to the subject of the Weybank again, after leaving the Cape Verde islands behind us it took only around two and a half days to reach the Spanish Canary Islands. I could once again listen to Portuguese Fado music from Madeira (which is only a relatively short distance north of the Canaries) and from the Portuguese mainland. At night I could also clearly receive BBC programs which were broadcast on long wave (200 kHz) from Droitwich.

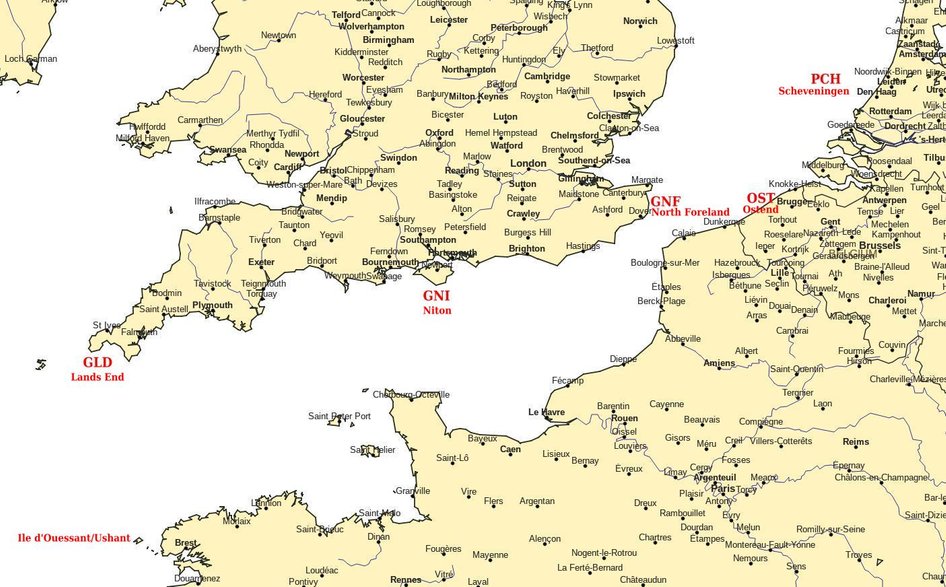

On the chart below our approximate course from the Canaries to the Ile d'Ouessant (Isle of Sheep) is shown in red and it takes us just about three and a half days to reach it from the Canaries. Ouessant (Ushant in English) marks the southern entrance to the western English Channel and is definitely a place we don't want to get too close to due to dangerous currents in its proximity. The photo below the chart depicts why. Ouessant also marks the most western point of France.

The only subject of any interest on our way to Ushant was when we reached the Bay of Biscay. For some reason when "homeward" bound I always passed through it at night and this time was no different. As usual there must have been around a hundred or so fishing boats ahead of us with their navigation and fishing lights dotting the horizon like christmas tree lights. These boats both Spanish and French fish with lines and/or nets and have the right of way meaning that according to international maritime law we are obliged to change course and circle around them, which our captain commanded to do so.

On a previous ship that I had served aboard we had also entered the Bay of Biscay at night and also on a heading for Ushant. I was on watch in the radio room when I heard the radar's rotary converter in the room next door start up. A few minutes later the hatch between the radio room and wheelhouse slid open and the 3rd mate's face appeared. "Hey Sparks, come and look at this" said he, sliding the hatch door shut again. I went into the wheelhouse but couldn't see much of anything of what he was pointing at because of night vision but I had a look at the radar screen and saw the pin points that the radar's beam had lit up. Like looking at the Cop end of Liverpool football ground during a Champions League match. At this moment the captain suddenly appeared in the wheelhouse - "Mr. xxxxx, are you f-----g blind or what?" (Mr.xxxxx being the 3rd. mate). "I was just about to call and inform you, Sir- permission to go around?" stammered the poor 3rd. "Go around? You are f.....g mad! He then ordered him to darken the ship i.e. extinguish all lights including the navigation lights and then without a change in course we proceeded to plough our way right through the middle of them. If it had been a full moon that night the captain might not have risked it. He was one of the real bad apples. The crew including the officers had long since learnt to despise him - some even had a hatred of him bordering on the insane.

Time is money at sea and anything that can slow us down is to be avoided if possible. Ship captains start getting nervous when closing in on the English Channel and I don't blame them because it is the most dangerous place in the world for a ship to be as far as traffic is concerned. Any serious mishap (e.g. collision, running aground etc.) can be a captain's career stopper whether or not he is directly to blame - he is responsible for the safety of his ship and crew – it comes with the job.

We "turned the corner" at Ushant into the English Channel under perfect weather conditions. It was the start of April and the high pressure weather system causing it remained almost stationary over the length of the channel, Belgium, Holland and Northern Germany and was still in place when I eventually signed off a few weeks later. However, for us aboard not being used to the colder climes it was chilly and it was time to change into our uniform "blues" (the actual colour of which is almost black with just a tint of blue).

Having not worn this (our "dress") uniform for well over a year I felt a bit of self-consciousness - who were we going to impress wearing it aboard such an unobtrusive cargo ship as ours? It was uncomfortable to wear as the material it was made from was heavy wool, the weight of the trousers required you to really tighten your belt to the point of strangulation. Wearing a tie again was another pain in the ass. If I remember correctly the name given to the uniform's material was Doeskin. Where they got this name from heaven knows - it conjures up images of supple, thin deerskin. The jacket however with the gold braid on the sleeves looked very snazzy but left a lot of empty space to balance out. The captain and my chief electrician pal Pat had both served with the MN during WWII and thus wore on their uniform left breast rows of what looked like miniature coloured flags but which were medal ribbons - very impressive!

The peculiar thing about MN officers concerning their uniforms is that they hardly ever went ashore wearing one, almost as if they were ashamed of it. Indeed, many a MN officer wouldn't be seen dead wearing one ashore. On the other hand there were the ones who took pride in wearing it. Sixty-five years ago, a member of the Marine Engineers’ Association (MEA) – a Nautilus predecessor union – wrote to the MEA’s magazine to lament the sartorial standards of his fellow seafarers. He urged them to wear their uniforms while ashore to 'remind the rest of the population that there is still a Merchant Navy'. His colleagues, he claimed, regarded the uniform 'as a badge of servitude to be worn by postmen, bus conductors and others, who show their contempt for the garb by making it look incongruous with coloured shirts and gaudy ties'. Quite what the writer would have made of today's boiler suits and baseball caps is a matter for speculation – but one thing is for sure, concerns about the smartness of seafarers are nothing new.

"Women love a man in uniform", or so it is said. Apparently this is a true statement if one takes passenger or cruise liners as examples. Aboard such vessels passengers also vie for the status of a seat at the captain's table, at least once per voyage. Some such passengers repeatedly return for a cruise on the same ship, strengthening their status - "How wonderfull to see you again" says the captain while thinking "God, the old bat's back again".

Aboard some passenger liners, P&O being one of them, certain of their officers were expected (ordered) to mingle with the passengers even to the extent of drinking with them in the ship's bars. They were paid an extra allowance for this "service". I can imagine the envy of male passengers seeing how some of the ship's officers in their uniforms attracted women to them like moths to a flame. On the other hand officers had to contend with the likes of things such as those explained below.

John Arton, an officer aboard the Empress of Canada wrote the following:

"Got rollocked by the Captain on the Empress of Canada for appearing in a photo with a tourist and not having my cap one. This occurred during a First Class bridge tour when the passenger in question was having her turn to get photographed steering the ship, grabbed hold of me, put my cap on her head and told the photographer to take the photo. All photos used to be posted up the next day in the foyer by the shops and the Captain used to examine them daily. The day after my photo sans hat had been taken I was on my way to post up the noon position and put up the miles steamed in the last 24 hours for the passengers raffle, when I saw the captain examining the photos from the previous day. He suddenly straightened up and stared closely at one photo, looking around he spotted me and beckoned me over, pointed at one picture that had a rather startled looking deck officer {me} with a females arm around my neck and her sporting my cap. He wanted to know why I had no cap on but when I explained that the lady in question, a dame of the British empire, had just grabbed my hat and put it on her head, he was somewhat pacified. After that we had to keep a spare cap on the bridge for passengers use only.

That particular bridge tour was memorable. The usual procedure for the 1st class bridge tour was for me to go to the 1st class lounge where the passengers would be sitting reading or writing up their journals whilst listening to the pianist tinkle the ivories and the bored 1st class barman polished glasses with no customers. The barman would announce to the room that anyone wishing to have a tour of the ships bridge should follow me. Most of the time I would only have one or two interested with most of them just looking at me as if I was an alien from outer space. This time though as I approached the lounge I could hear raucous chatter and laughter coming from the lounge and on entering was greeted by the sight of a very harried barman trying to keep up supplying a large group of passengers, led by a very smartly dressed, well spoken middle aged lady {who turned out to be a Dame} whilst the poor pianist tried vainly to make his tinkling of the ivories heard. On my presence been announced this whole gang fell off their bar stools and demanded pitchers of cocktails off the barman for them to imbibe whilst they were on said bridge tour. I led this gang of them, along with all their drinks, up to the bridge all the time wondering what I let myself in for and what the Captain would say if he witnessed it all, probably nothing as they were 1st class.

Once I had them all on the bridge they were more akin to a bunch of school kids on a days outing. Trying to maintain any sort of order was nigh on impossible, they were just wandering around drinking and attempting to play with any and all the gear. I just managed to stop one of them from ringing full astern on the telegraph's, he had asked me what they were for and I explained that they controlled the engines {could not be bothered to explain steam turbines to him} and thus the ships speed. He had his hands on them and was about to ring them astern when I got to him before he could actually move them.

Trying to keep a bunch of half nizzed 1st class passengers in line on a bridge tour was one of the most exhausting experience I ever had whilst I was on the Canada".

Having worn our Calcutta tailor-made jungle green uniforms for now over half a year, they had been beaten almost to death by our Dhobi Wallah and the time had come for Pat and I to give them a ceremonial burial at sea.

The English Channel is approximately 300 nautical miles (nm) in length, 130 nm breadth at its widest and only 18 nm at its narrowest at the Strait of Dover.

If we could maintain our 15 knot speed (not taking into account any currents which may be running against us or making collision avoidance detours) it would take us 20 hours to traverse. It was already daylight when we entered by Ushant so we would cover only just over half the distance before the sun went down.

In the chart above I have marked the positions of the main coast stations that I monitored along the way. The radio traffic on the 500 kHz calling frequency was overwhelming - I had not heard such cacophony since we had left the channel the year before. I could judge our progress through the channel by the signal strength of the coast stations which would rise until we were abreast of them and then slowly decrease the further we advanced. Sailing through the channel I listened especially to the general calls from Lands End, Niton and North Foreland. These stations not only transmitted scheduled weather reports but also navigational and safety warnings on their working frequencies - as did also French coast stations. Sadly, these and all the other similar coast stations were relegated around twenty years ago into history's bin. Some ex-R/Os managed to save tape recordings of morse traffic on 500 kHz and have posted some of them on YouTube - "those were the days my friend, we thought they'd never end".

In 1969 when sailing through the channel it was a case of "everyman for himself". Only two years later, following an accident in January 1971 and a series of disastrous collisions with wreckage in February, the world's first radar-controlled traffic separation scheme came into operation. The scheme mandates that vessels travelling north must use the French side, travelling south the English side. There is a separation zone between the two lanes.

The closer one got to the Dover Strait the more dangerous the situation became not only because it forms a bottle-neck for incoming and outgoing ship traffic but because of cross-channel ferries. The major ferry ports on the Continent are Calais, Boulogne, and Dunkirk in France and Ostend in Belgium (longer routes are from Cherbourg, Normandy and Brittany). Ferries from these ports sail mainly to either Dover or Folkstone.

Adding to the ship ferries, in 1959 the first Hovercraft crossing occured taking just over two hours between Dover and Calais. Hovercraft entered commercial service in August 1968, initially between Dover and Boulogne but later also between Ramsgate and Calais. The journey time Dover to Boulogne was roughly 35 minutes, with six trips per day at peak times. The fastest crossing of the English Channel by a commercial car-carrying hovercraft was 22 minutes, recorded by the Princess Anne on 14 September 1995. When crossing through the Dover Strait I often saw these hovercraft however if the wind increased above around Beaufort 4 or 5 and thus the wave height, they had to suspend crossings otherwise the wave motion would cause the air cushion on which they lifted to collapse.

Cross-channel ferry traffic also increased due to "Booze Cruise" - tax duties on alcohol and tobacco on the continent were generally lower than in the UK - a bottle of beer would cost less than half of what one would pay for it in the UK and thus the ferry operators increased the number of their daily crossings accordingly to meet the demand.

Today a Dover to Calais ferry will take 90 minutes to cross the English Channel. One ferry operator alone offers 9 different Cross Channel routes, with up to 744 ferries sailing a week across the Channel. Its most popular route, the ferry from Dover to Calais has up to 35 sailings a day.

Even with the control and monitoring technology in use today it is still a mystery to me why there are so few "accidents", to put it mildly.

We managed to escape the channel unscathed and now headed up the Dutch coast where to pass the time a bit I would listen to one of my favourite coast stations - Scheveningen Radio PCH. Their VHF and HF telephony channels were mainly "manned" by girls who all were friendly and had an enticing lilt to their English - conjuring up visions of sweet blonde Dutch "Meisjes". When terminating crew members' radio telephone calls via PCH I was often on the verge of asking "How about a date?" but managed, in the knowledge that these were open radio channels and half the MN world was listening in, to reluctantly restrain myself.

Below is a link to a video of Scheveningen Radio PCH made around the 70's/80's:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HnAj-xcD8gc

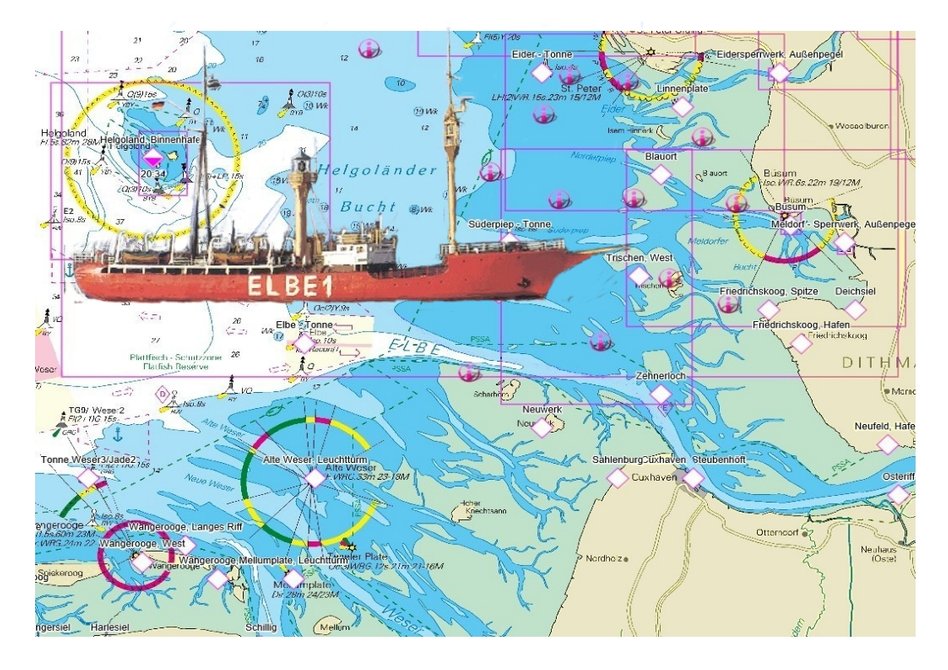

Leaving the coastal chain of the Dutch West Friesian islands behind we now headed eastwards along the chain of the German East Friesian isles until the day arrived when in the early morning hours just after the sun had risen - there she was - the Lightship "Elbe 1". For a German seaman seeing her once again it is a sight to see - "home again at last".

On the 09. November 1949 the lightship Elbe 1 went into service in position 54° 00' 00"N, 08° 06' 35"E. Within the next 39 years she would survive many near-collisions and a number of severe actual collisions requiring her often to be removed from station to undergo shipyard repairs. On the 22. April 1988 she was finally removed from service and replaced by an unmanned automatic light-buoy named the Elbe Tonne - shown at the mouth of the Elbe in the same 58°N 08°E position in the chart above. The Elbe 1 lightship however avoided the breakers yard. She is now a museum ship but is still afloat and seaworthy.

A total of six almost identical pilot vessels (built between 1958 and 1964) patrolled the mouths of the Elbe, Weser and Ems rivers. Three of them were stationed at the Elbe, two of them at the Weser and one at the Ems. The pilot ships took up position near the Elbe 1, Weser/Jade and Borkumriff lightships respectively. Normally only one vessel at a time patrolled its respective lightship area.

The pilot vessels crew quarters were forward, up to 44 pilots had their messroom on the main deck and their sleeping quarters on the tween deck aft.

The ships were twin screwed with diesel-electric propulsion giving them a speed of 13 knots, had a length of 55.10 m, breadth of 9.50 m and a displacement of 767 BRT. The last of them to be replaced by modern vessels was the Kapitaen Koenig which served until 2015.

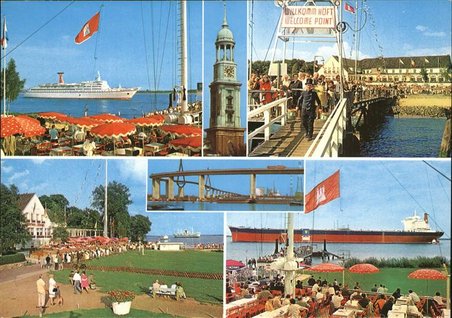

On our arrival at Elbe 1 it didn't take long before a cutter from the pilot vessel came alongside. The Sea Pilot boarded - he would con us as far as Brunsbuettel whereafter the River Pilot would board to take us the rest of the way to Hamburg. The weather remained beautiful as we commenced our journey up the river. The pilotage to Hamburg is long and it was only by mid-afternoon that we came abreast of the Willkommhoeft ship-greeting station/ restaurant (see Chapter 1) at Wedel/Schulau on our port side. Two 1960's postcards of this station are shown below.

Hier doppelklicken, um Ihren eigenen Text hinzuzufügen.

We could hear a German commentator announcing our ship's name and further details to the guests over a loudspeaker system. Our national anthem was played and they raised the Union Jack (it might have even been the Red Duster - they were that organized - I can't remember). We saluted them with blasts from our fog horn as we cruised by. It was here that I noticed a launch leaving the pier at Schulau and then speeding towards us. Our gangway was already lowered when she came alongside and two people jumped aboard. They were shown up to the bridge where we discovered it was our German ship's agent together with his girlfriend whom he had taken along for an outing. She was an all-in-one German version of Bridget Bardot, Ursula Andress and Dolly Parton - a real head-turner and she knew it too. She was also pretty smart and could give as good as she got - all eyes were glued on her including the pilot's and its a wonder that we didn't run aground on one of the sandbanks. I had asked the pilot where we were going to berth and he told me the name of the wharf but that we would not be going alongside, instead we would be moored to Dalben.

The name Dalben is derived from the Dutch language. It is a column of wood like a very thick telephone pole or a bundle of them called Duckdalben which are rammed into the harbour ground and serve to either moor ships to or as in the case of the Kiel Canal to guide ships along to the lock gate entrances.

Below is an old photograph of part of Hamburg Port showing clearly the Dalben and how the ships were moored to them. These types of Dalben were still in use in the 1960's and we tied up to them in the exact same way. The wood used in Hamburg Port in the 60's was a hardwood called Basralocus which is highly resistant to salt or fresh water. The longest Dalben were almost 18 meters in length and weighed over 5000 kg!

In the last few years the remaining of these Dalben were also finally removed from the Hbg. Port and replaced with modern substitutes with material other than wood. A German company specializes in making furniture from these discarded Dalben - the wood has retained all of its good properties.