Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 5

Tanganyika Territory - German East Africa - Tanganyika - Tanzania

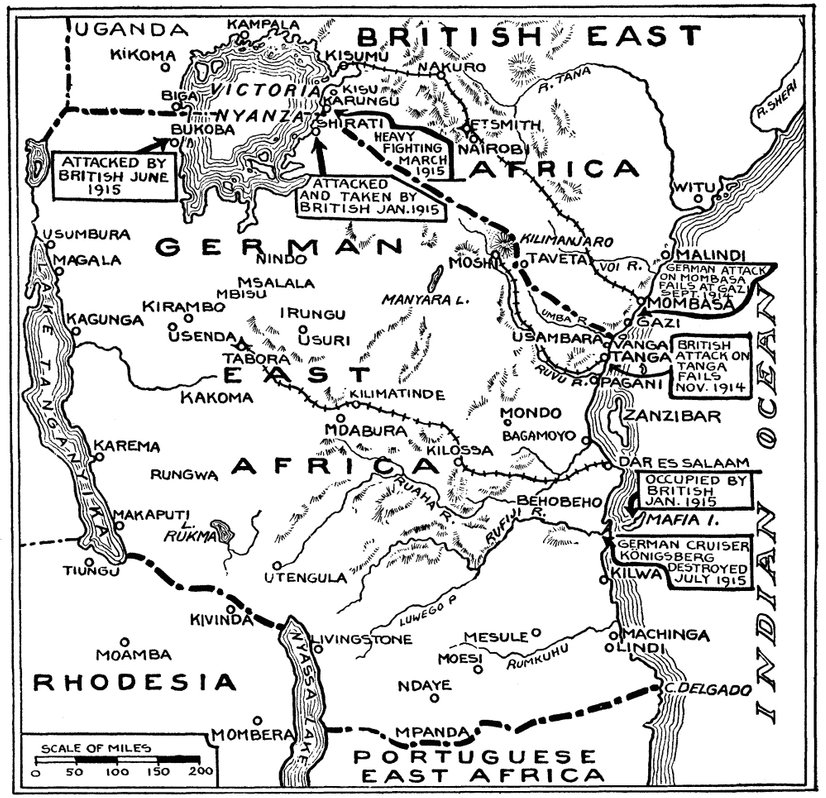

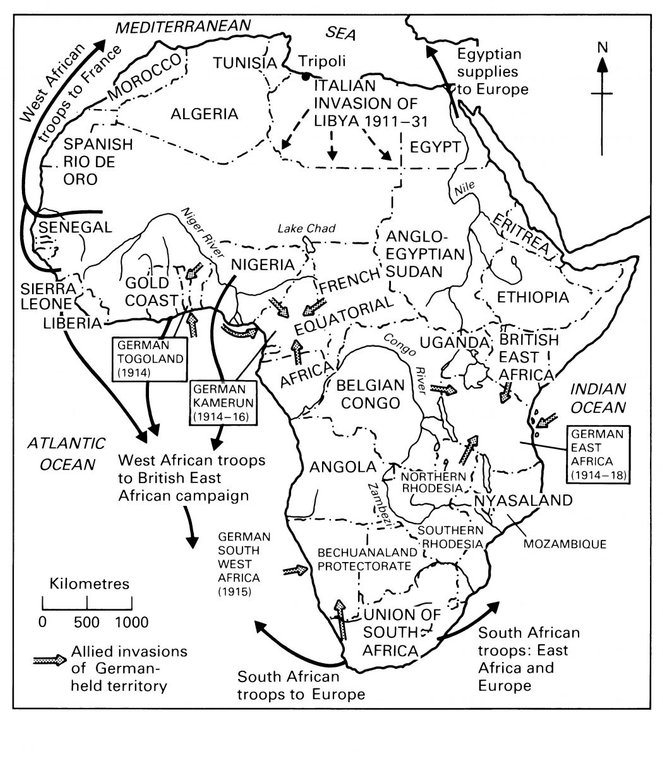

Tanga, Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar are all ports in Tanzania we often called at. Before describing some of these visits I will give a brief history of Tanzania with the aid of the maps above which will be of aid in finding place names and understanding circumstances:

Tanganyika Land's recorded history dates back to the days of Portuguese traders, who established a trading post in Tanga during the 16th century and controlled the region for the next 200 years.

The Sultanate of Oman battled the Portuguese and gained control of the region by mid 1700 along with Mombasa, Pemba Island and Kilwa Kisiwani.Tanga continued to act as a trading port for ivory and slaves under the sultan's rule until 1873 when the European powers abolished the slave trade.

In the nineteenth century in a coastal strip under the jurisdiction of the Sultan of Zanzibar the principal port was Bagamoya, an open roadstead port a few miles north of Dar-es-Salaam. At that time Bagamoya was also a port of embarkation for the slaves brought down from upcountry by Arab slavers.

In 1857 the Sultan decided to turn the sheltered landlocked harbour of Dar-es-Salaam into a port and trading centre. The popular myth is that he left his chief wife in charge in Zanzibar and took his favourite concubine with him, calling his new port Dar-es-Salaam or Haven of Peace. In fact, although he built a grand palace and other buildings the project did not prosper, the vested interests in Bagamoya and the narrow winding entrance channel with it's strong tidal currents which proved difficult for the Arab dhows and other sailing ships to navigate caused the scheme to be abandoned.

Nothing further was done until the advent of the German East Africa Company towards the end of the century (1891) to whom the Sultan granted (for about the equivalent of £200,000) the right to develop ports and raise custom dues. By now the advent of steam ships, which had no difficulty in navigating the entrance channel, made the sheltered harbour of Dar-es-Salaam much preferable to the open roadstead of Bagamoya as a port. This was amply demonstrated in 1892 when several large units of the German navy entered the inner harbour.

The start of the construction of the Railway from Dar-es-Salaam to Lake Tanganyika made port improvements imperative. Dar-es-Salaam quickly became a large and thriving port and an Administrative capital. The port facilities were improved by the provision of wharves, dockyards and a floating dry dock. The Secretariat and other large Government buildings were built and are still used for similar purposes by the present Administration today.

Tanga became the first German establishment in East Africa (Tanganyika Land) and also the centre for the German colonial administration before the establishment of Dar es Salaam. In Tanga the Germans built a tram line to facilitate domestic transport and also built a port to facilitate exports. The Usumbara Railway began in 1896 and was later extended to Moshi by 1912. They also brought in sisal which, combined with a functioning infrastructure, saw the economy of Tanga expanding to be next to none in German East Africa. As the coastal town closest to British East Africa (Kenya), Tanga was on the front line at the outset of World War I. A British landing was thrown back on 4 November 1914 in the Battle of Tanga, and the town was not taken until 7 July 1916.

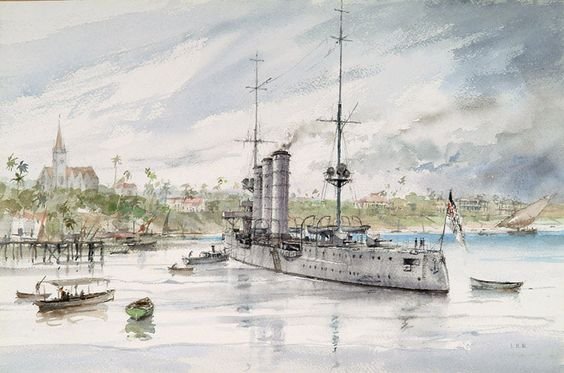

With the advent of WWI, the German light cruiser S.M.S. Koenigsberg (launched in 1905) arrived in Dar-es-Salaam in June 1914 where she created quite a sensation. With three funnels she was known to the Africans as the "manowari wa tomba tatu" (the warship with three funnels) and was thought to be all powerful, a reputation that the fate of H.M.S. Pegasus (only two funnels) amply demonstrated. They were not to know that the simile would come full circle when the Koenigsberg herself was soon to be destroyed by a naval force which included H.M.S. Chatham with four funnels. In January 1915, the British occupied the island of Mafia and Dar es Salaam was shelled by British warships - the Germans unsuccessfuly sunk a floating drydock at the harbour mouth in an attempt to block the harbour mouth.

The Koenigsberg, after sinking H.M.S. Pegasus at Zanzibar on the 20th. September 1914 took refuge from the pursuing British Naval forces in the delta of the Rufiji River where she was eventually trapped and put out of action in July 1915 by naval gunfire. The Germans scuttled the ship but not before removing and landing heavy guns and anything else of use ashore. The crew then managed to join up with German land forces in East Africa under the command of Lt. Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck who, after defeating the British in the Battle of Tanga, succeeded, with the aid of Koenigsberg's guns, in leading the British forces on a wild goose chase around East Africa until after the Armistice was signed in 1918.

In 1919, under the League of Nations, Tanganyika became a British mandate with Dar es Salaam remaining the administrative and commercial centre. The name "Tanganyika" is derived from the Swahili words tanga ("sail") and nyika ("uninhabited plain", "wilderness"), creating the phrase "sail in the wilderness".

Above - an excellent watercolour painting (probably painted in 1914) of S.M.S. Koenigsberg at anchor in Dar es Salaam harbour with St. Josephs Catholic Cathedral prominent in the background.

Below - the Koenigsberg lays scuttled in the Rufiji River.

In 1947, Tanganyika became a United Nations Trust Territory under British administration, a status it kept until its independence in 1961.

British rule (which lasted 42 years) came to an end on December 9, 1961, but for the first year of independence, Tanganyika had a governor general who represented the British monarch. On 9 December 1962, Tanganyika became a democratic republic.

After a revolution overthrew the Arab dynasty in neighbouring Zanzibar, which had become independent in 1963 (since 1890 it had been a British Protectorate), the archipelago merged with mainland Tanganyika on 26 April 1964. On 29 October of the same year, the country was renamed the United Republic of Tanzania ("Tan" comes from Tanganyika and "Zan" from Zanzibar).The name of Zanzibar comes from "zenji", the name for a local people (said to mean "black"), and the Arabic word "barr", which means coast or shore.

In 1967, Tanzania took a turn to the left commiting to socialism as well-as Pan-Africanism. Banks and many large industries were nationalised. Traditional trade links with Portuguese Mocambique became things of the past as Tanzania supported Frelimo and other Mocambigue "freedom fighter" groups permitting them to open training/build-up/R&R sanctuaries within the country. East German "peace corps" brigades appeared in Zanzibar and started implementing building and other aid projects.

Chou en Lai paid a visit to Tanzania soon after (when the "Cultural" revolution in China was in full frenzy) and it didn't take long before it appeared as if they were managing the whole country. They financed and with hordes of Chinese "imported" for the job, built a 1,860-kilometre-long railway from Dar es Salaam to Zambia which took 5 years until completed in 1975.

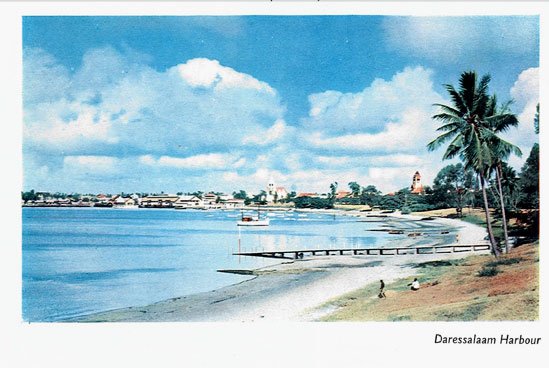

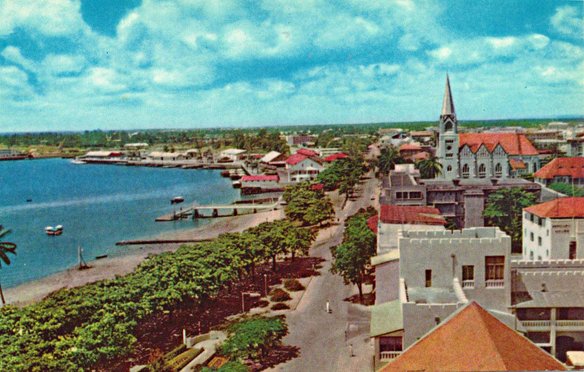

Dar es Salaam

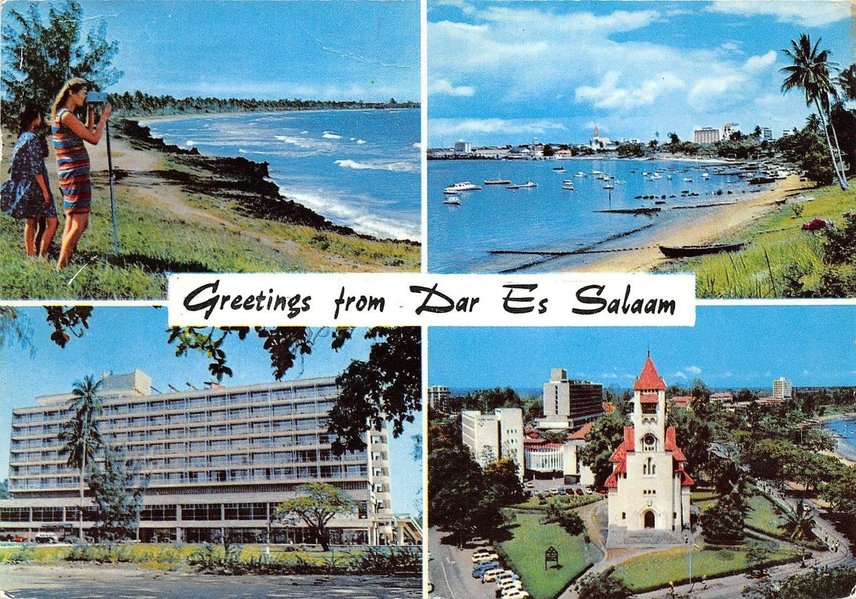

Dar es Salaam ("Haven of Peace" in Arabic) in 1968 indeed lived up to its name as it was a very beautiful looking little town when viewed from the waterfront with the only prominent features being the spire of St. Joseph's catholic cathedral and the tower of the protestant evangelical church. It had nothing to offer a seaman in the way of nightlife such as the bars of Mombasa, Beira, Lourenco Marques or South African ports did and it was thus sometimes called "Sleepy Hollow".

Above a photo taken in the 1950's - St.Josephs's in the centre and the evangelical church tower to the right

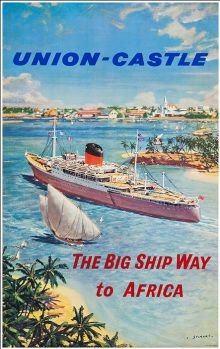

Above left - DeS waterfront in 1970; Above right - 1960's poster of UC ship entering DeS harbour

Postcard from the early 1970's - ugly high-risers already ruining "Sleepy Hollow"

We frequently called at DeS but never tied up at a pier, instead always dropping anchor in the harbour bay and loading or discharging cargo into lighters or dhows that tied up alongside.

To pay a visit ashore we had to use one of our lifeboats and arrange for a pick-up time for the return trip. DeS had many imposing buildings that had been built by the Germans including the cathedral and church mentioned above and were well worth visiting and there were lovely beaches in the vicinity as well such as Oyster Bay.

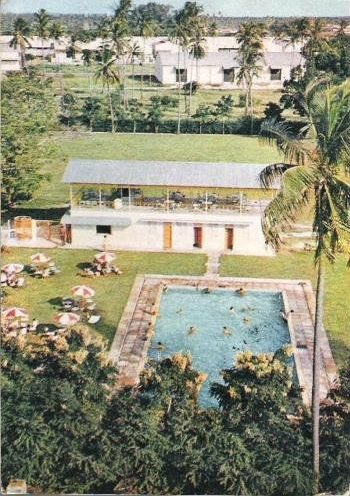

After having "seen the sights", most of our other visits ashore (and at later calls to the port) were to play football matches organized by the Flying Angel Seaman's Mission or to swim and have a drink at the mission's swimming pool.

Also, since Tanzania had turned socialist/communist just a year before in 1967 and was being wooed by the Russians and Chinese, we Brits were not exactly on their hit list.

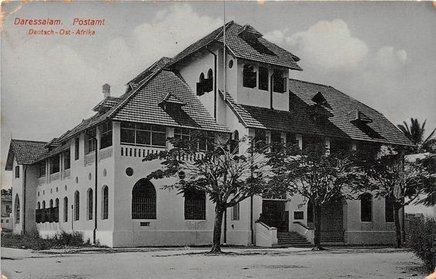

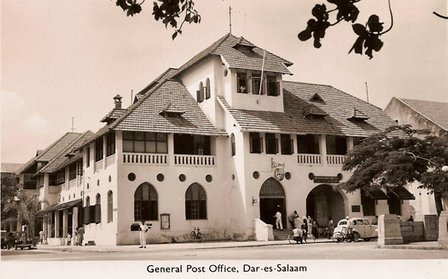

Above, top left, German photo of the Post Office as built by them.

Above, top right, British postcard of the same building but taken many years later (this building ist still standing today in the middle of DeS)

Above, bottom, the Flying Angel swimming pool.

Tanga

If Dar es Salaam was "Sleepy Hollow" then Tanga was "Suspended Animation"!

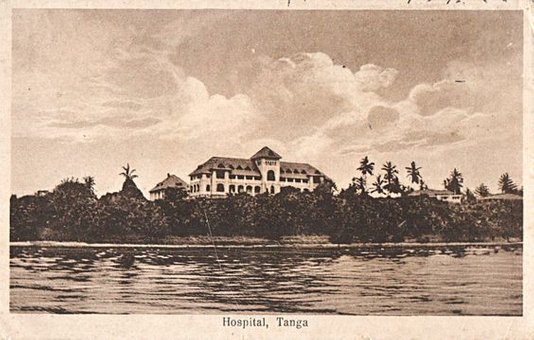

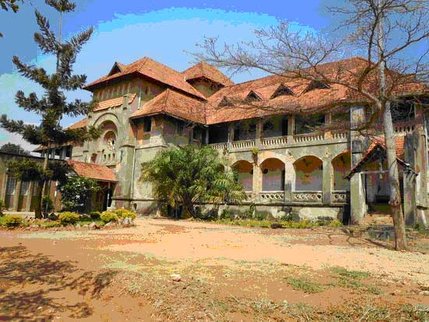

Tanga was like DeS but in a much smaller scale, a picturesque bay with a harbour town. Again the architecture of the superb buildings the Germans had built (and throughout German East Africa) were the main (only?) attractions left in Tanga apart from the seafront gardens.

As in DeS we were always at anchorage but our stays were very short, a day perhaps - two at the most.

Sadly most of the buildings the German's built have been neglected and are falling to ruin although it is probably fair to say that Tanzania itself just doesn't have the money to be able to restore them. However, since international aid has enabled the restoration of

for instance the Anglican Cathedral in Zanzibar, there may still be hope.

Above - the German built Bomba Hospital in Tanga - a b/w British photo taken after WWI. The colour photos underneath show the abandoned delapidated state of this magnificent building today.

Above left - a German East Africa b/w photograph of Independence Avenue (as it is now called).

Above right - the same avenue in colour shot in 2012 - the view is of the same street side but shot from just left of centre of the b/w photo.

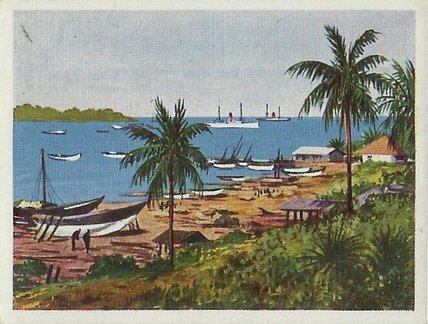

Nostalgia - on the lhs a German East African artist's depiction of Tanga Bay; on the rhs Tanga waterfront in 2012

Zanzibar

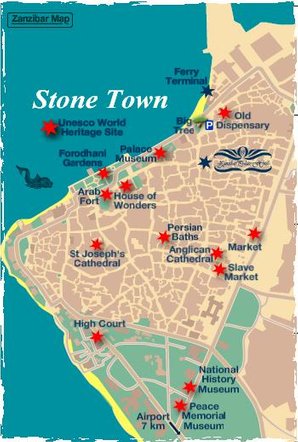

Zanzibar is an island that lies just to the NE of Dar es Salaam. The town which is the capital of the island is also named Zanzibar but is generally called Stone Town which avoids confusion.

The Weybank only called in once, anchoring off Stone Town. Viewing the waterfront alone of Stone Town you could clearly see most of the main attractions. When we went ashore the only places we could gain entry to were the Anglican Cathedral and the Arab Fort - all the other buildings in the list below were being used as government offices at the time. Otherwise, the town was interesting to say the least with narrow passageways between the buildings, many of which were built in Arabic style.

There was only one "Seaman's Bar" in the town which was a dead loss and Zanzibar, belonging to Tanzania had also gone down the socialist/communist path. In fact I think Zanzibar got a jump start because after the revolution which threw out the sultan, Zanzibar was the first non-socialist country to recognize the German Democratic Republic (East Germany)- this shortly before Zanzibar merged with Tanganyika to form Tanzania.

Below are two contemporary photos of Stone Town and a map showing the location of the main attractions.

The first is a panoramic view of the waterfront- in it to the right you can see a church spire (St.Joseph's Cathedral) and to the left of the spire a white tower which is part of the House of Wonders. Between the HoW and the church spire lies the Arab Fort (hidden by trees). To the left of the HoW lies the Sultan's Palace (white buildings with arches and red roofs) and further to the left is "The Big Tree".

The second photo gives an aerial view in which you can clearly see the Arab Fort to the right of the HoW.

Slave Market

Mid-19th century Zanzibar’s streets were teeming with slaves, some on transit to other destinations and others brought to work on the Island’s clove plantations.

Slaves brought to Zanzibar came from an area that extended from the south of Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi), west of Lake Tanganyika and north of Lake Victoria. Not all slaves in Zanzibar came from Africa, women were brought in from other continents for the sultan’s harems. Caucasian and Mesopotamian slaves were among the most prized. Up to 30,000 people a year were shipped over in dhows and imprisoned under appallingly cruel conditions before being sold at an open slave market.

Slaves came to predominate the population making about two thirds of the Island’s population.

The Slave trade as abolished in 1873 but slavery as an institution persisted in Zanzibar until 1909. Master slave relations and clandestine kidnappings continued at least 2 decades longer.

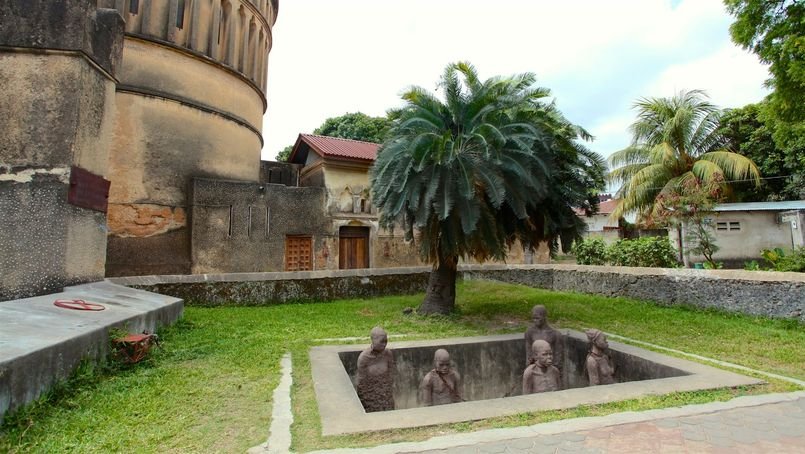

Anglican Cathedral-Church of Christ

The grim reality of the slave market hits home on a guided tour of the Anglican Cathedral, built by British missionaries over the site where slaves were tied and whipped before being sold. A peek inside the dingy, windowless cellars beneath the ground, where up to 75 slaves were kept at a time with no food, fresh air or toilets, is sobering to say the least.

The Christ Church was built in seven years, the foundation stone being laid on Christmas Day 1873 until the opening on Christmas 1879. The construction of the cathedral was in fact intended to celebrate the end of slavery. As most buildings in Stone Town, it is made mostly of coral stone. When I visited it in 1968 it was in deep decay - a sorry sight to behold.

However, international monetary aid was granted in approx. 2010 for restoration and now in 2018 it is almost completed.

Outside the cathedral in the cathedral gardens, a monument to the slaves was built in 1998 by the Scandinavian artist Clara Sörnäs. It shows five slave figures, slightly larger than life, chained together (with original chains) in a pit. They are men and women, young and old, with features that show the variety of tribal and ethnic backgrounds.

The House of Wonders

Beit al-Ajaib is called the House of Wonders because it was the first building on the island to have electricity and running water and one of the first in east Africa to have an electric lift . The commanding, elaborate building on the waterfront was built in 1883 by Sultan Barghash as a ceremonial palace. From 1911 it was used as offices by the British colonial government and after the 1964 Revolution it was used by the ASP, the ruling political party of Zanzibar though today in 2018 it is home to the Zanzibar National Museum of History and Culture.

The Arab Fort

The Arab Fort is next to the House of Wonders. It is a large building, with high, dark-brown walls topped by castellated battlements. It was built between 1698 and 1701 by Omani Arabs, who had gained control of Zanzibar in 1698, following almost two centuries of Portuguese occupation.

In the 19th century the fort was used as a prison, and criminals were executed or punished here, at a place just outside the east wall.

In 1949 the fort was rebuilt and the main courtyard used as a ladies' tennis club, but after the 1964 Revolution it fell into disuse.

Today, the fort has been renovated, and is open to visitors.

The Palace Museum (Sultan's Palace)

This is a large white building with castellated battlements situated on Mizingani Road, where the latter runs very close to the sea. Originally called the Sultan's Palace, it was built in the late 1890s for members of the sultan's family. From 1911, it was used as the Sultan of Zanzibar's official residence, but was renamed the People's Palace after the 1964 Revolution, when Sultan Jamshid was overthrown. It continued to be used as government offices until 1994 when the palace was turned into a museum

The Old Dispensary

Opposite the new port buildings, on Mizingani Road, this is a grand four-storey building with a set of particularly decorative balconies.

It was originally built in the 1890s as a private house for a prominent Ismaili Indian merchant called Tharia Topan, who was a customs advisor to the sultans, and one of the wealthiest individuals on Zanzibar at the time. In 1899 he gave the house up to be used as a dispensary, also funding the medicine and other services. Topan also provided money (with the Aga Khan and Sultan Ali) for a non-denominational school which opened in Zanzibar in 1891.

The dispensary fell into disrepair during the 1970s and 1980s, but was renovated in 1995 with funding from the Aga Khan Charitable Trust. A few years later it opened as the Stone Town Cultural Centre.

The Big Tree

Just west of the Old Dispensary, about 100m along Mizingani Road, is a large tree originally planted by Sultan Khalifa in 1911. Known simply as the Big Tree (or in Swahili as Mtini – the place of the tree), it has been a major landmark for many years and is still clearly visible on the seafront from ships approaching the port. Today, traditional dhow builders use the tree as a shady 'roof' for their open-air workshop.

(David Livingstone is the best-known of all the European explorers who travelled in 19th-century Africa, and many of his journeys began and ended in Zanzibar).

The Russian Fishing Fleet

If I hear anyone today mention Zanzibar my memory immediately recalls a Russian fishing fleet - not Zanzibar itself. The reason being no doubt that as we were approaching the anchorage at Zanzibar, all we could see were Russian ships at anchor, at the very least there were sixty of them. The majority of them were trawlers, but there were also a few refrigerated transport ships and refrigerated factory fish processing ships among them (I had seen such a massive fleet before in 1964 anchored at Singapore for the same purpose of replenishing with fresh meat, fruit, vegetables and water).

When in action at sea, which they were just about 90% of the time, a trawler would trawl until its holds were full and then draw up alongside one of the big fish factory ships (which would have anchored beforehand) and discharge his catch into the holds of the factory ship. A factory ship would then later in turn discharge its frozen processed fish into refridgerated transport ships which once full would head off to a destination port.

Because they spent so much time at sea their hulls and superstructures were covered with rust or red or orange streaks where the outer paint coating had succumbed to the salt and had exposed the protective anti-rust primary paint coating, which in places had also succumbed and the hull itself started to rust - giving the false impression that they were all imminent candidates for ship-scrapping yards.

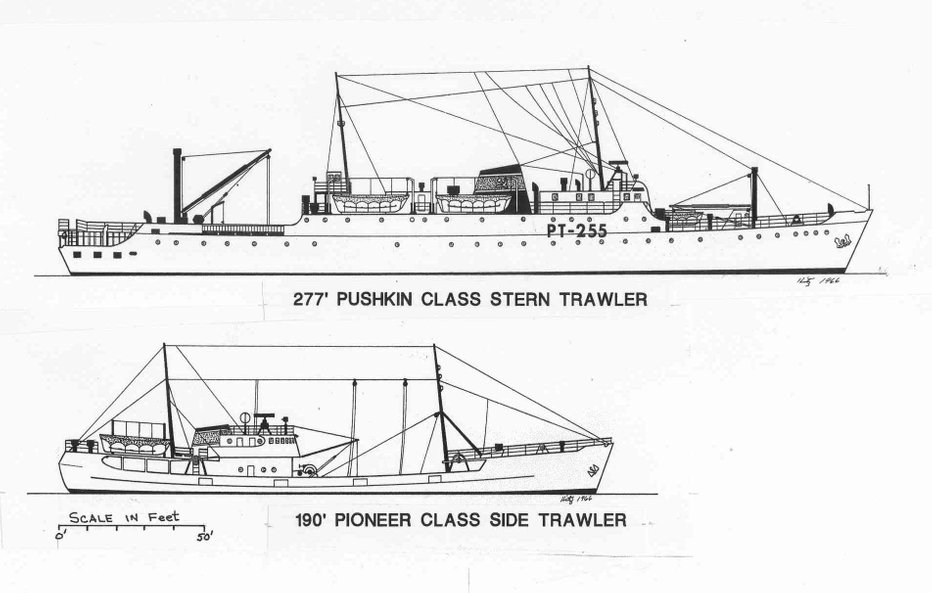

To the left is a series of Soviet Russian postage stamps issued in 1967 in recognition of the service Russian fishing vessels gave to the "Rodina" - the Motherland. From the top:

Pushkin class stern trawler.

Refridgerated transport vessel.

Fish processing/conservation factory vessel.

Pioneer class side trawler.

Chernomorski class seiner.

Below a photo of a factory vessel and a drawing of Pushkin and Pioneer class trawlers

The following text was written by Carmel Finley who in 1966 was aboard an American trawler off the Pacific coast of Washington State in the USA and it leaves nothing to the imagination in explaining the fish scavenging efficiency of such fleets:

"I got out of my bunk, dressed and went up the steps to the pilot house, sensing the coming daylight as I came onto the bridge where Pete, the skipper, said “We have company” and as I looked out the pilothouse windows I saw a sight that stunned me.

There was no wind; the sea had a slow glassy swell. To the east was the coast of Washington State with the Olympic Mountains in the background, with the sun starting to show above the horizon and reflecting off the ocean. Everywhere else there were ships, a huge fleet of Russian ships and as the sun rose the red hammer and sickle on the stacks seemed to glow from the reflection. It was a Russian city as close as three miles off the coast of Washington, unbelievable during the cold war when we saw only a vessel or two when we worked there or transited though the area.

A 125’ Russian side trawler, a rarity on the Pacific coast, crossed our bow, looking us over. It was fascinating seeing such a vessel in our waters after reading about them in the fisheries literature. It was low in the water, the house aft with a flush deck, with trawl doors hanging from fore and aft stanchions on the starboard side. The vessel ran smoothly through the water, lifting on a swell and rolling to starboard toward the Cobb. The trawl winches just forward of the house could be seen with hatches and checkers forward of them. She was long and low like a canoe, pointed at each end. There were more vessels of this class, cloned from the same mold, a ship referred to as an SRT. They were catchers, not processors, so their catch had to be off-loaded that day to a processing ship anchored nearby.

Looking around I saw other classes of side trawlers as well as a few of the new 280 foot stern trawlers, a new concept to the distance water fleets of the world. They were large, high and long with a stern ramp where the trawl net would be hauled, dragging the catch up behind similar to whaling factory ships that pulled up the carcasses to be butchered. Once the fish were on the upper deck they would be dumped through a hatch to the factory below decks to be processed, frozen and stored in the freezer holds as food fish. The waste would go to the fish meal plant, dried, bagged and stored in a dry hold. Livers from the gutted fish would be converted to oil, using all of the waste product. Again the ships seemed to be cloned, numbers of the same class of stern trawler seen, mainly the Mayakovskiy class.

In the distance were processors, the freezer ships and support vessels making up this enormous distant water trawl fleet working off the Washington coast. It was unbelievable that they were there. They had found the hake concentration we were there to scout and this fleet of at least 50 ships was taking them. What chance could four west coast combination fishing vessels have and what about our other fisheries? What effect would this have on them?".

East London

When sailing along the South African coast from Capetown to Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban or vice versa it was usually in conditions of beautiful weather. The sea a dark blue with white capped waves under an azure sky and day after day we could clearly see the white surf and beaches of the coast (SA has about 1,800 miles of beaches!). The coastal terrain would also change from for instance the rugged mountainous cape region to the rolling hills of the verdant green sugar plantations as we approached Durban from the west.

In 1968 the only tourism in SA was purely domestic and "white" apart from white Rhodesians "getting away from it all" in land-locked war torn Rhodesia. Over ten years later this situation had not changed. Enver Mally who later in life became chairman of the board for Cape Town Tourism said "In the 80s, as a non-white person, I had no clue that an industry like tourism existed, for us, it was very difficult to travel to places.” (Today in 2018 about 10 million tourists visit SA annualy).

In 1968 the total population of SA was only around 21 million of which about 4 million were whites (today in 2018 the total population is well over 50 million but at best the white population is still less than 5 million).

SA - on the one hand beautiful magnificent scenery and on the other Apartheit.

The white population which was only a fifth of the total population dominated the country by force.

The whites owned 87% of the land; the ratio of average earnings was 14:1; for the black population the ratio of doctor/population was 1/44,000, for the white 1/400; the ratio of annual expenditure on education per pupil was 15:1. The government dictated the types of employment open to black employees (mainly manual such as working in the diamond mines or "gofor" jobs) and those which were not.The black population had to carry identification papers which enabled the government to control and restrict their movements.

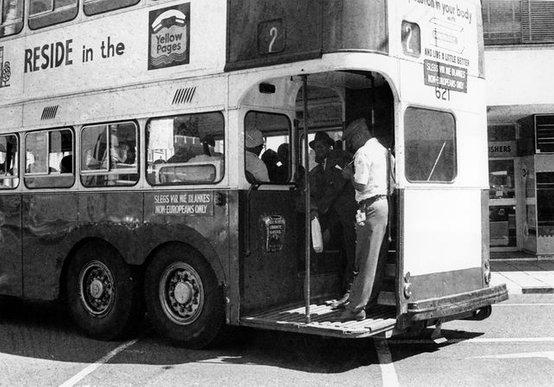

The segregation was appalling - no matter where you turned you would see "whites only" or "blacks only"

signs written in Afrikaans and English. At toilets, bus stations, taxi ranks, restaurants, cinemas, public buildings, offices, railway station ticket offices, beaches, drinking fountains, parks and park benches. Separate schools, separate this, separate that, ad infinitum. In southern US states like Georgia or Alabama busses were segregated - whites at the front, blacks at the back. In SA they went a step further - busses for whites and busses for blacks.

The indignity suffered daily by the black population must have been awful - I would guess that at that time most white households employed maids, cooks or nannies - sometimes all three. Very often, especially if the household included children, the maid, cook or nanny would come to be almost regarded as one of the family but at the end of the day she would have to find her own way back to her "township" shanty town (hoping she wouldn't get mugged on the way). Her "home" would be more or less a glorified shack hammered together with bits of scrap wood or with breeze block walls if lucky and a corrugated iron roof. Working all day in a household that "has it all" and returning in the evening to your own "has next to nothing".

When I went ashore in SA it was always with a sense of misgiving. The white population would think that you were one of them and the black population would likewise think that you were a white South African. To top it off, we didn't know the rules of the game. The meaning of the "whites/blacks only" signs were obvious but what about other rules which were not? Where were the townships located in the respective town or city? Could you wander into one of them without noticing? Were whites allowed to enter townships and if they were would they come out alive? Could you help an old black lady cross the street?

None of us aboard made any acquaintances with white South Africans which wasn't surprising. In any port of call it's not as if you can announce yourself with a "Hey, it's me, I've arrived" but in SA if we went into a "whites" bar any conversation that we had with the locals would sooner rather than later turn to the topic of Rhodesia. Why we Brits were stabbing our own kith and kin in the back? etc., etc. Apartheit was a taboo subject, unless you were a fascist. (In the US in 1967 I experienced similar "conversations" in bars but the subject was Vietnam - why were we Brits not fighting alongside them against the "commies"? "In WWII we saved your asses and for what?, bunch of cowards!").

The only port I really appreciated in SA was East London. In 1968 it was just a small town/harbour in a picturesque area at the mouth of the Buffalo River. From the harbour a 2km esplanade road led to a beautiful secluded beach which I visited whenever I got the chance and would also go for walks on the bluffs above.

The first photo below from the 1960's shows a Japanese freighter departing East London harbour. You can clearly see the wide esplanade road which followed the coast line up to the beach and bluffs at the top of the photo which I mentioned above.

The next photos shows the beach just NE of EL. In the first one you can see the EL suburbs.

Before moving on to Chapter 6 - for all amongst you who wished they had gone to sea but never did, just look at what you missed!