Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 1

My story of the Weybank starts at Aldergrove Airport which was at that time the name of Belfast airport in Northern Ireland. It was originally called Nutts Corner Airport. Aldergrove rapidly became a by-word for the Press in the mid-1960's when the "troubles" in N.I. really escalated because it also served as a hub for military traffic in and out of the country.

On a rainy cold February morning in 1968 at the age of 21, I boarded a BEA (British European Airway's) Vickers Viscount aircraft. It sounds like something from the Great War so to avoid any confusion, I have included a photo of it below which was taken at Nutts Corner.

As you can see, it is a propellor driven aircraft and the noise the four engines made was unbelievable. Airline passengers today could sue an airline to death if they had to put up with such a decibel level on a flight. We took-off for London but unfortunately only got half-way there.

I myself would gladly have suffered the prop noise a bit longer but London was covered in fog so the pilot had to divert to Manchester. We were then all dumped into buses (which the airline personnel called "coaches" because it sounds posher and they probably thought it would make us feel thankful to them for not shoving us on buses) and started our long trundle down the motorway.

The weather was getting worse and after a few hours I was beginning to despair of reaching London in time for my signing-on. I was employed at that time by The Marconi International Marine Communication Co.Ltd. abbreviated MIMCO but which I will just call Marconi. (If you think that is a mouthful - I was much later employed by a German company called the Deutsche Betriebsgesselschaft für Drahtlose Telegrafie G.m.b.H but the Germans are also not stupid and hence copyrighted their abbreviation DEBEG).

MIMCO spoken in English "rings a bell " with Charlie Chaplin or "Les Cirques du Soleil"; DEBEG when spoken in German sounds in English like "Daybeg", however , in German it carries a tone of authority, finalization, something not to be messed about with, especially since 99.9% of Germans don't know what it is or means.

Marconi had an office in East Ham in London. Being a Scot myself the only places I was familiar with in London were mainly railway stations. I could help an extraterrestrial out with a map of the moon but not a tourist with a map of London.

Marconi couldn't give a monkey's about our map reading abilities - Marconi office personnel were supposedly all ex-R/O's but like most officials "knowledge = power" and some of them acted accordingly, trying to make us feel like we were at the headmaster's office at school awaiting some unknown punishment.

By the time I reached London and finally found my way to East Ham, it was already dark. When I announced my arrival I was shown into a waiting room where there were a few R/O's already waiting ahead of me.

It was then that I heard a loudspeaker up on the wall blaring away in Morse Code the name of the next R/O to come forward into the main office.

Instead of simply opening the door and introducing himself with a "hello" and a handshake....

When it was my turn I was informed that the ship was the "Weybank" of Andrew Weir & Co.; that she was in Rotterdam and that there was a boat train leaving in a few hours to Harwich from where I would board an overnight ferry for the Hook Of Holland. Great! - I already knew that the Bank Line was a "never come back line" and that he was lying through his teeth when he said that the voyage would only be for three months.

They always lied about this because if a vessel stayed within "Home Articles", the so-called continental area which was basically Europe, a crew member could leave the vessel after three months whereas if the vessel went "deep sea" then by law you would be obliged to stay with the ship for as long as two years before you could legally leave. The company would then have to pay your fare back home. If you wanted to leave within the two year limit, you had to yourself first arrange for a replacement, pay his fare out to wherever the ship was at the time and also pay your own fare back to the UK.

This was financially out of the question - the cost of international air travel at that time was astronomical as for that matter was a passenger ticket aboard a passenger vessel.

I officialy was "Engaged" to the Weybank that same evening - that's the wording of the column "Date and place of Engagement" in my "Seaman's Record Book and Certificates of Discharge" under which was entered

"8.2.68 London" so from that moment on I was by law a member of her crew.

I don't remember how but I eventually arrived at Liverpool Street Station carrying my suitcase (holding mainly my uniforms) and a holdall. It must have been around 19:30 hours (that's navy-speak for 7.30 p.m.) by the time I got there. Sometime later I boarded the "boat train" and off we chugged to

Harwich Parkeston Quay.

The oil sketch above is of Liverpool Street Station ten years later - No wonder we all wanted to escape!

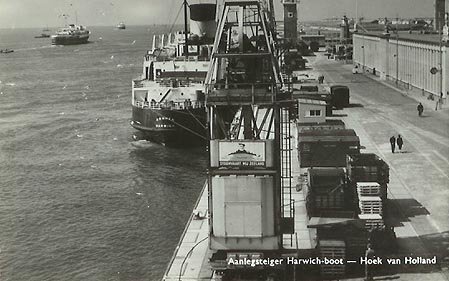

It must have been about 23:30 before I boarded the ferry in Harwich. She was the "Arnham", shown in the two photographs below which served on the the Harwich - Hook of Holland route at that time.

Marconi out of the goodness of their hearts payed the rail transport and also the ferry fare which included a cabin reservation! It turned out to be about the size of a dog kennel but it came in handy for stowing my gear safely away. I never saw the cabin again until the next morning when I picked up my gear again.

As you have probably guessed by now I spent the rest of the night in the ship's bar which for some forgotten reason stayed open most of the night.

In the bar I met all the other crew members who were also on their way to

joining the Weybank. There were not too many of us on the ferry - The Master (Captain) and his wife; the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Mates; the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Engineers; the 1st and 2nd Electricians and two apprentices.

The Master, his wife, the 2nd and 3rd Mates, the 4th Engineer, the 1st Electrician and both apprentices were Scots like myself - after all the Weybank was registered in Glasgow! The rest were English including the 2nd Engineer who was Anglo-English. Only the Chief Engineer, the 6th Engineer and the Chief Steward were missing at this point (and about 55 other crew members who were mainly Indian, had joined the ship months ago and were aboard her in Rotterdam waiting for us so that they could finally sail back to the Weybank's unofficial home port of Calcutta).

When we arrived at the Hook it was still lousy weather. The Dutch name "Hoek van Holland" translates as the "Corner Of Holland".

We disembarked the ferry and then boarded a bus which transported us & our gear to Rotterdam. It was foggy and drizzling a fine cold rain when we arrived at some unknown quayside whereupon we had to board a small tug-like boat to take us across to the Weybank which was moored somewhere in the middle of the "Nieuwe Maas" meaning the "New Maas"" of the River Maas. Having no cargo at the time, the Weybank was "high out of the water" - in other words towering above us as we pulled up alongside. We all had not eaten since the day before (no nice leasurely breakfast upon arrival at the Hook - ever!) and I was thinking to myself "If this is just the beginning.....".

The painting above is a Dutch artist's impression of the "Nieuwe Maas" in the 60's. Instead of the "Cap Vilano" ship as the eye-catcher it could have been the Weybank instead, except for the weather!

As the crew members which we were to relieve were still not ready to disembark, we spent another few hours sitting around in the Officers Mess (this is a room found aboard most ships which you could compare with a teacher's congregation room at school - it is not the actual mess which the departing officers left behind themselves). Your opposite "number", in my case the R/O who was departing, is supposed when handing-over to give you a run through the radio room, its equipment, paperwork, radar etc. etc. and give you any useful information - like what he had himself experienced aboard. In my case this didn't happen because he had made himself invisible. I first met him when he was on the way to the gangway (which is the long "staircase" lowered down the side of a ship - not to be confused with the Pilot Ladder which is real ladder made of wood and rope).

I finally found my cabin, checked out the radio room and then had a walk around the vessel when I was pointed towards a large wooden crate lying on the main deck which was waiting for me. It contained a Marconi Argonaut VHF Transceiver, something wonderous that I had never seen before. Luckily the "Old Man" (the Captain/Master) said that it would be installed by a German company at our next port of call, Hamburg. He also told me that we would drydock there for about three weeks whereafter we would load cargo for our next port of call. Happy days!! Off to Hamburg!

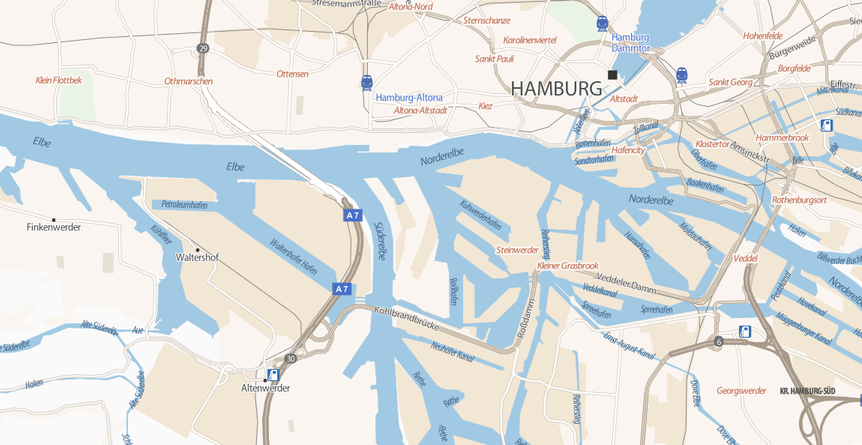

On the map above you can see both Rotterdam and Hamburg. Hamburg lies on the River Elbe.

The satellite photo shows the Elbe with Hamburg visible where the Elbe suddenly thins.

The Schiffsbegrüßungsanlage Willkomm-Höft (literally, Ship Welcoming Station Welcome Point, Höft being Low German for headland or point) is a facility at the Schulauer Fährhaus (Schulau Ferry Building, a restaurant) in Schulau, the southern district of Wedel on the Lower Elbe. It was founded by Otto Friedrich Behnke on June 12, 1952.

Ships heading upriver for or downriver from the port of Hamburg are welcomed or bid farewell by dipping the Hamburg flag and by hoisting the international flag signal for "bon voyage" (letters U and W). For vessels over 1,000 GT leaving German waters, the national anthem of their country of registry is additionally played between 8:00 AM and sunset or 8:00 PM. Occasionally, the ship will return the greetings by dipping her flag or sounding her whistle.

For the welcomes and farewells, there are recordings of 152 different national anthems of maritime nations, or rather of those that keep a register of shipping, and welcoming and farewell messages in the local language. These are available on compact cassette (red lettering for welcome, black lettering for farewell) and computer. Both systems can be used interchangeably.

The ship welcoming station is notified on arriving and departing vessels by the Hamburg nautical registration office once an inbound ship has passed Stadersand or an outbound ship, Hamburg Finkenwerder. Visitors are briefed on each ship by loudspeaker. Information includes name, nationality, date of construction, builder, operator, length, beam, and draught. Plus, if applicable and known, container capacity and trivia. These data are stored in a constantly updated, handwritten card index on about 17,000 ships.

The ceremony of ship welcoming and farewell is performed in turn by six so-called "welcoming captains". Aboard the Weybank we were fortunate to pass the Willkomm-Höft about midday and were greeted with the flag-dipping and national anthem etc. which I find is a nice touch from a seafaring city such as Hamburg is.

The map above is of the heart of Hamburg. The "Kiez" written in red on the map is the famous "red light" area where the Reeperbahn and the Herbertstrasse are located, for those of you "in the know". The "Blohm & Voss" shipyard is located directly below the Kiez on the lower bank of the Elbe. When our drydock overhaul was completed, we moved to a berth in the Waltershofer Hafen to load cargo for Karachi, Pakistan (as we had by this time ourselves been informed of - still time to "jump ship"!).

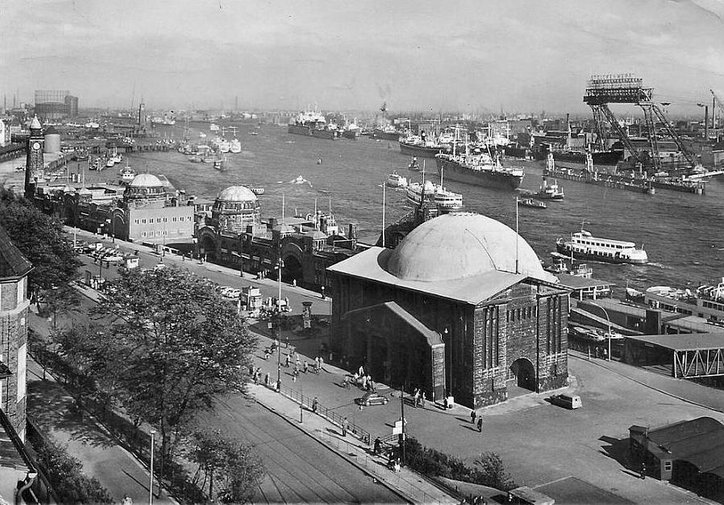

We often crossed in the evenings from the shipyard with a ferry to the Landungsbrücke

(Landing Bridge - which is actually a number of floating pontoons moored together and connected to shore via bridges). It is one of the most famous locations in Germany. It is also only a stonethrow to the Kiez.

This is how the Landungsbrücke looked about eight years before I was with the Weybank. You can imagine the bomb damage caused during the war. The two small green domes to the right of the clock tower mark the location of the Landungsbrücke.

The Landungsbrücke mid-sixties when I was there. You can see the Blohm & Voss shipyard directly across on the other side of the Elbe.

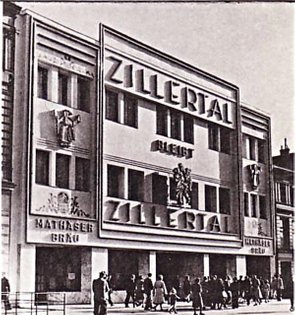

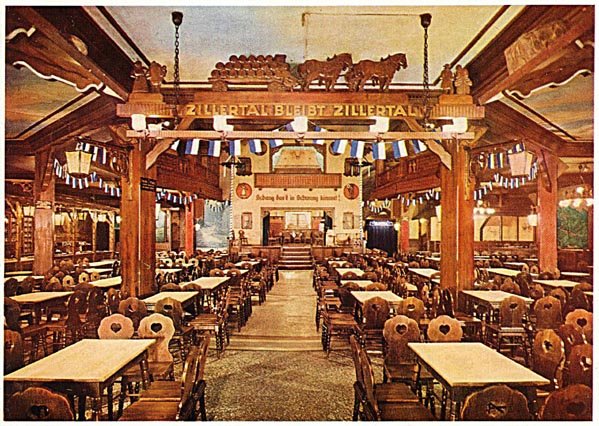

Being seamen we didn't see much else of Hamburg at that time and ended up in places like the "Zillertal" which is a Bavarian-type beer hall which always had a Bavarian band on the go. If you bought all the band members a drink you were allowed to conduct them. If too many tourists did this, the music suffered progressively! At intervals everyone had to get up off their benches with their beer "Steiners" in their hands and climb up onto the long tables and sing "Ein Prosit, ein Prosit der Gemütlichkeit...." or "Hoch soll Er leben...." or similar beer drinking hits. All good clean fun until one night Donald M. our 4th Engineer wouldn't get down of the table after the music stopped and instead kicked the beer mugs of several Italian seamen (who were sitting at the same table) into their faces. There is a balcony running around the top of the beer hall and out of the corner of my eye I saw the bouncers already on their way .... I will never forget that the Zillertal entrance/exit was a big wooden & glass heavy revolving door! Outside on the street I was busy learning Italian the hard way - I can especially recommend the word "Vafancula" for anyone who wants an Italian to kill him.

Another "main attraction" was the Herbertstrasse which is a side street blocked off from public view by a tall wooden barrier to stop mainly women from being able to look down the street. It is a street both sides of which are lined with shops just like the Co-op or "Boots" except that the wares behind the glass windows are "Bordsteinschwalben" (Kerb Swallows) wearing not much and in many cases sitting knitting out of boredom waiting for their "watch" to end. Through mimicry a prospective customer would be directed to a side door and thankfully for them (although not all) to a room at the back.

A woman could not enter the Herbertsrasse without being accompanied by a man. Even then she did so at her own risk - many a woman has had a bucket full of p... thrown down on them by the swallows.

So much for some of the main attractions - there were and still are many more and some of them would make the Herbertstrasse sound like a Kindergarten.

The Kiez however is not how Hamburg should be remembered as it is a beautiful city with a long heritage and its own culture. Ten days before we were due to sail I met Inge. We were married in Hamburg when I returned there with the Weybank fifteen months later.

The weather was very cold at the time and Hamburg was covered with snow and ice. Icebreakers had to break up the ice on the Elbe. While in drydock I spent my days continuously checking the radio & radar and other Marconi equipment - replacing weak components etc. and making up new wire antennae which were made from copper wire.

I had been informed that a German company called DEBEG for short (similar to Marconi) would install the new VHF transceiver but after a few days nothing had happened. I telephoned the DEBEG and was told not to worry, it had not been forgotten. The weeks went by and still the same assurances were made during my subsequent calls. Finally a week before we were due to sail, a happy young German arrived with his carpenters box and drill etc. and asked me where I would like to have it - he meant where should he install the VHF. I marked out a position in the Chart Room for the transceiver unit and its rotary converter and another one in the Wheelhouse for the operator's control unit. He also asked me to show him where the "mains" cable could be connected to and finally where the antenna was to be sited. He then merrily spent the rest of the day and half of the next drilling, hammering, running cables etc. until he proudly announced "Alles fertig" (all ready/done) and invited me to switch-on - just like launching a ship. I went to the control unit in the Wheelhouse and switched the on/off switch to the on position and - nothing happened - or so I thought until I turned around and saw that all the Loading Lights were illuminated. These are big lights which shine on the holds to enable cargo to be loaded/unloaded at night. I switched the control unit off and the loading lights extinguished. We now had an expensive LL remote control station.

Once the wiring was sorted out the VHF (Very High Frequency) transceiver appeared to be functioning perfectly ( I found out soon enough that it was not!) and indeed this type of radio revolutionized coastal and port radio communication. It is a radio telephone with which the speaker could communicate with tugs, radar stations, pilot vessels, port authorities, other ships and at that time amazingly hold a normal telephone conversation with just about anyone in the world via a coast station link. Its only drawback is that it has a range of only on average roughly 20 nautical miles (depending on the weather atmospherics, the strength of the transmitter and the height of the antenna - the higher the antenna is mounted, the further the distance that can be covered which is why this kind of VHF transmission is called "line of sight" - the higher you stand, the further you can see). At the time that it was installed on the Weybank there was another drawback in that as it was so new, ships and coast stations were just starting to be fitted with one, if at all because they were not compulsory. Because they cost money, there were at first plenty of shipping companies that ignored or were unaware of the benefits that it could bring.

The Weybank loading cargo at the Waltershofer Hafen in Hamburg before departure to Karachi.

Finally the sad day arrived - on a freezing snowing dark February evening we slipped our moorings and as the tugs slowly pulled us out from the pier I waived to Inge until I could see her no more.

Ice breakers had broken up the ice on the Elbe and so the tugs were free to tow us out of the Waltershofen Hafen and into the Elbe where, after letting them go we slowly moved down river with a German pilot aboard towards the mouth of the Elbe, where it flows into the North Sea.

Blankenese is a suburb of Hamburg which is sited on higher ground on the north bank of the Elbe where many a rich banker or shipping company owner has a villa. After passing Blankenese there is nothing much else to see in the dark.

An oil sketch of Blankenese on the Elbe in summer

Zillertals's front entrance and its beerhall inside

After Blankenese, I hung around for a couple of hours and then went to my cabin and "hit the sack". The next thing I knew the 1st Mate was in my cabin - "Sparks - get up! The radars f.....!". In my subconscience I had been dreading this moment. In Hamburg I had the radar running everyday to try and detect any "gremlins" but they hid from me real good. Now they were in my face.

I stumbled up to the bridge and through the chart room entered the wheelhouse.

The wheelhouse at night is an enforced "dark zone" where "Dark Vader" awaits any idiot stupid enough to enter while shining a light. A light switched on at night in the wheelhouse blinds the bridge personel from being able to see outside into the dark.

Just as serious is the effect when the light is switched back off again. The eye cannot rapidly readjust to the darkness again, it takes at least 5 minutes before night-vision is regained.

In my present predicament I was in a kind of "Vice Versa" situation - I came out of Osman's light zone (most of our light bulbs aboard at that time were from the Osman Co.) and entered Dark Vader's. Guess what! - Right! - I could see f... all.

When I entered the wheelhouse I became immediately "blind as a bat" but my ears were still functioning. I even asked questions in the dark like "where are we?" This question hit the jackpot - we had left the Elbe 1 Lightship (stationed at the mouth of the Elbe) behind us and were following the German coastline with the aid of the radar, until the radar decided to self-destruct. It was snowing and visibility was next to "Zilch". As the Yanks say: "Houston, we've got a problem".

Oil sketch of the Elbe 1 lightship

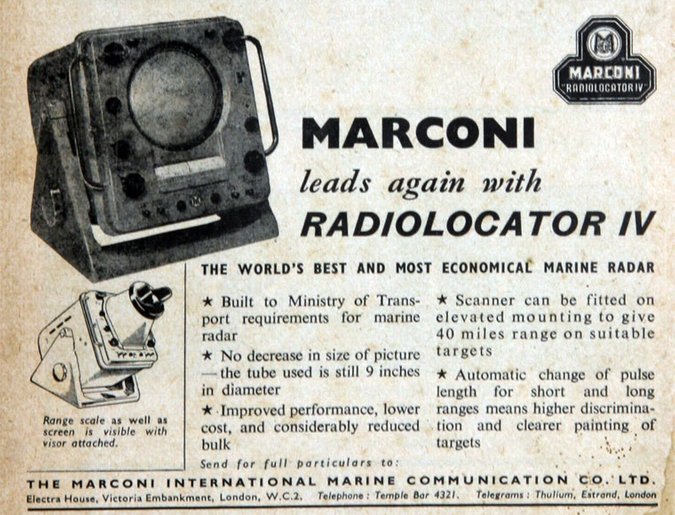

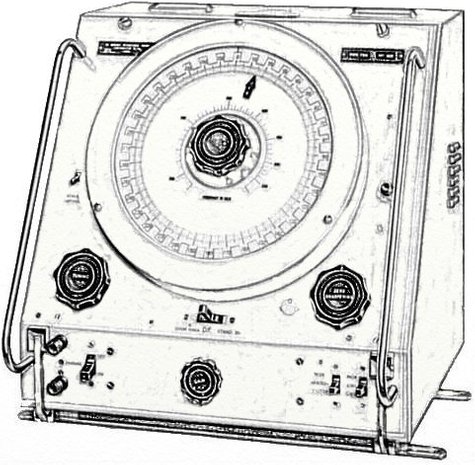

The Radar Console in the Weybank's wheelhouse appears from a distance like the President of the United States's press podest from which Bill Clinton told us "I never had sex with that girl". Instead of Bill Clinton, think back to my age - Richard Nixon - "Tricky Dicky"! The difference between what Bill or Richard were trying to sell us and what our meagre console (when functioning) truthfully indicated is "day and night". Our podest contained a CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) which gave us a PPI (Planned Position Indicator) display. All hot stuff at the time! Just to stop your imagination running wild, here's a photo of it:

Above is an advert from about 1951 when the Radiolocator IV was introduced to the world!

It is unfortunately also the only photo that I can find of it. This is the operator console. The main unit of this radar is the transceiver which had the dimensions of a large fridge but did the opposite - it produced heat as a by-product. It had the approximate dimensions of an old red GPO telephone box apart from the height which was about level with the top of my head when I was standing (no, I'm not a dwarf). The transceiver unit was installed in the radio room recessed into the bulkhead (navy-speak for wall). It was only a couple of feet behind where I sat tapping away on my morse-key. The transceiver made a high pitched sound like something you would expect from a flying saucer but probably because the radio equipment made a much louder racket when transmitting, the radar noise never bothered me.

Returning to the advert above, I love the bit under the small insert where it says "Range scale as well as screen is visible with visor attached".

The CRT screens of British radars had an Amber (orange toned) display whereas US and Russian radars used green toned displays. This is because of "nightsight" in a dark room - amber and green do not blind as much as white light does but they still blind nevertheless.

Viewing a radar screen in daylight was also a problem, light reflecting off the glass of the CRT screen for example. Try watching your TV with the sun shining on it through your window and you get the idea.

The "boffins" at Marconi came up with a marvellous solution - a hood which they named a "Visor" just like Sir Lancelot wore - well, not quite. Marconi's visor was a metallic conus

which at first was capped with a rubber eye-protective viewing top-piece, later to be replaced with a plastic version. At sea the rubber would rapidly deteriorate and the deck officers all started looking like the Lone Ranger - press the eye zone of your visage against the rubber and pick up an imprint, to the delight of the engineers aboard: "Me Tonto, Kembo Sabi?".

Back to "Range scale as well as screen is visible with visor attached" - now for the fun bit -

what is the sense in attaching a visor if the screen would then become invisible - or even worse: "With visor unattached, screen is invisible".

Meanwhile, back at the Ranch, somewhere in the North Sea, I had to get the radar running.

After tripping my way in the dark to the radar console I saw that instead of a rotating strobe there was only a bright flimmering dot at the centre of the screen. I immediately thanked God for helping me out - I had seen this effect before, and not just once!

I told the 2nd Mate who was almost at the end of his watch that I was going to have to switch the radar off and then after a time on again and then off again and then...

The fault was caused by two large "bottles" which sat proudly next to each other in the radar transeciver. These were vacuum filled glass valves whose job was to drive the dot at the centre of the screen to the screen's periphery thus producing a strobe, This strobe is synchronized with the revolutions of the radar antenna. The rotating strobe "paints" the CRT screen like the seconds hand of a clock and thus displays targets such as buoys, ships and German islands! The manufacturer of our spare-part valves that we received were mainly "Mullard" but recently we started to get "Brimar" valves which although advertised as a British company distributed valves made behind the "Iron Curtain", for example in Poland. The valves employed for the strobe had to be high standard which was not the case of Brimar's. Both of the valves involved had to balance their workload. Like human beings, if one became weak, the other would pick up his load. The more exhausted the one became the other was glowing first orange and then red hot until he eventually died - Adieu strobe!

Now my work really began because after replacing the valves I had to carefully monitor if one of them started to work harder than the other and if this was the case I would have a "Deja Vue" experience - back to square one - new valves, try again.

Stabilization is the name of the game - everyone happy again. I went into the radio room and after heated up the main transmitter and main receiver (not with a blow torch! The radio equipment is valve driven and the valve filaments need about 3 minutes to heat before they can be operated) I sent a Traffic Report (TR) to Norddeich Radio, the main German coast station. When leaving a port and in this case after having passed through the 3-mile limit of German territorial waters, a TR with the name of the ship, position, port of destination and ETA (Estimated Time of Arrival) must be transmitted, in this case to DAN (the callsign of Norddeich Radio). In the event of us disappearing off the face of the Earth a TR would at least give those left behind us a clue as to where to start a search.

I then went back to my cabin to try and get some sleep before I had to go on watch.

Again the 1st Mate is in my cabin but this time he really has the watch (the 2nd Mate's prayers have been answered and although he is still on the bridge he hasn't got the responsibility any more) - it must be after 0400 GMT!

"Sparks, we're lost - you've got to take a bearing!" This must be a dream but no, it's the real thing. I went into the chartroom to find out where they thought we were or at least where our last known position was and then went into the radio room to do some magic with a lodestone like Mickey Mouse, the Sorcerer's apprentice.

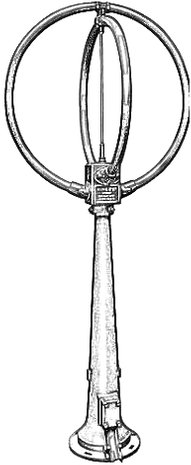

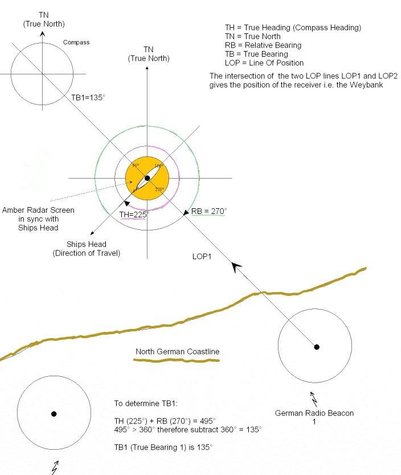

The lodestone that I have to play with is a Direction Finder equipment which Marconi named the LODESTONE. The Lodestone's main unit is a special kind of receiver which has a Goniometer (nothing do do with Gynaecology) inside apart from the usual valves and wiring etc. It has a unique antenna called a "Bellini-Tosi" (no relation to Benito Mussolini) which is shown below together with the receiver and also has a Sense antenna.

I will try and explain as short as possible in layman terms roughly how I could determine our ship's position. It starts with books! In the radio room there is a bookshelf which holds all (better said those that fitted) the mandatory radio-related publications to be carried aboard. Since we were lost, I had to fish out a volume titled "List of Radiodetermination and Special Service Stations" and then thumb through it hoping that the Federal Republic of Germany was inside (with my luck up to now I'd probably only find the DDR - East Germany, not much use unless your ship is in the Baltic Sea).

I'm in luck, I can hardly believe it. There in front of me in black & white is listed a chain of FRG Radiobeacon stations. A radiobeacon chain can contain up to six separate beacon transmitters each of which has its own callsign and transmission particulars. They share the same transmission frequency but each transmits at an alloted time within the chain's cycle schedule. The List gives their exact positions in Latitude and Longtitude.

In the interim I had not forgotten to switch the Lodestone on to let it heat up! Now I went back to the chartroom to determine the location of each of the beacons on the sea chart.

Back to the radio room - put the horrible headphones on and plug them into the Lodestone.

The Loadstone did not have a loudspeaker - the headphones are heavy, unwieldy contraptions where at least one of the earpieces had the habit of unscrewing itself , dropping down and swinging like a monkey on the wire it was still attached to - unbalancing the contraption overall usually ending with the other earpiece trying to strangle your left eye.

With the aid of a big black knob on the Lodestone which Marconi thoughtfully had labelled "TUNING", I turned it until I could hear the chain's transmissions. I waited for the start of the chain's next station transmission and then turned the big black knob right at the centre of the dial until I acousticaly got the bearing and then noted down on paper the number of degrees it was showing on the dial. To determine whether the target beacon was in front of or behind me, I pressed the Sense switch (if for example the bearing on the dial indicated 90° it could be lying to me and instead be the reciprocal which is 270°- by pressing the Sense switch it would acousticaly tell me which one was true).

Sound's a bit complicated? If you were at some time a Boy Scout you will be in your element here. After having taken the first bearing from that chain's particular beacon, I still did not know where we were. I now had to do some mathematics - not my forte!

A ship's orientation with the rest of the world starts with "Ship's Head" or even worse "Ship's Head Up" and I am sorry to tell you that it has nothing to do with sex.

The Radiolocator IV's radar screen is calibrated as a 360° circle (360° = 0°). The Ship's Head on the radar screen is 0°. The Ship's Head is relative to an imaginery line of axis drawn down exactly through the middle of the vessel from bow to stern and indicates where the bow (instead of the stern) is pointing. Therefore, if a ship is sailing West the Ship's Head is 0°, if it sails East, no change, still 0°.

The Bellini-Tosi D/F antenna had been installed just like the radar antenna - calibrated to "Ship's Head Up". I had already recorded (wrote down on a piece of paper) my first D/F bearing, taken from the Weybank in her lost meandering but relative to our Ship's Head and the location of the radiobeacon sited on terra firma. Navigational Charts carried aboard however are orientated to the True and Magnetic North.

I then had to transpose my "relative" bearing by "addition and/or substraction" to a "true" bearing which would "fit" on the navigation chart.

But, not so fast; before I could run into the chartroom shouting something like "Give me 5" (this expression did not exist at the time and neither did "Hasta La Vista, Baby") I had to consolidate my biblical knowledge by taking "cross bearings". I need to take at least one other bearing, preferably two and each from a different radiobeacon station within the cycle until we can by triangulation "pinpoint" our position ("marblepoint" would be more like it) on the navigation chart.

Back to the chartroom where they are awaiting me like priests in the Spanish Inquisition - my calculated position scribblings are hastily taken to the chart table and then after a flurry of protractors/slide rules/parallel rules/pencils etc. are marked on the chart. The inevitable question is awaiting and it arrives: "Are you sure this position is correct?".

"Of course it's correct" I indignantly answered (lying through my teeth) - the only way anyone of us could truthfully answer the question would be if we could see something outside that we could identify on the navigation chart. The weather and thus the visibility was still bad and the radar still had not targeted anything that would help us. We were still ploughing ahead (time is money) and I repeatedly took new bearings to track our supposed position.

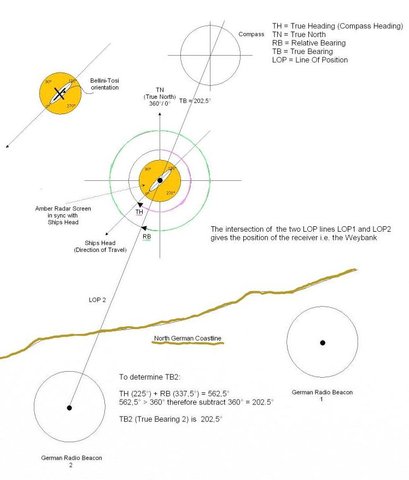

A navigation chart has a Compass Rose - the outer circle shows true bearings; inner circle magnetic. A special kind of ruler as shown below is placed over the CR on the first bearing and then by a parallel zig-zag action placed on the edge of the radio beacon whose position is already known and then a line drawn. This is repeated with the second bearing from the 2nd beacon; where the two lines intersect, that is the ship's position.

If you read the Radiolocator IV advert, it states "Scanner (antenna) can be fitted on elevated mounting to give 40 miles range on suitable targets". It is probably true providing the elevated mounting is on the top of the Empire State Building and a suitable target being something like an aircraft carrier. Although the radar's highest switchable range is 40 miles, its normal true highest target range, (similar to the VHF range) is around 20 nm, half that advertised.

Not long after, the radar picked up a buoy which could be identified on the sea chart and this confirmed that the D/F bearings were correct. We now had become unlost!

From this moment on the 1st Mate became a believer. He turned into a "D/F Geek" as will be seen later. There was not much sense in my trying to get any more sleep so I went into the radio room to get organized for my first sea watch.

Apart from the R/O the crew has a 4-hour on, 8-hour-off watch cycle to follow and the clocks used are in GMT Greenwich Mean Time. For instance:

The R/O has a different schedule which is not a fixed schedule but depends on in which of six time zones labelled from A to F the vessel is currently positioned. The Weybank will sail through three of these time zones A, B and C which cover half of our planet.

The North Sea and the Eastern Atlantic Ocean is covered by Zone A and so until we reach Durban in the Western Indian Ocean my hours of watch are as follows:

From (GMT) | To (GMT) |

0800 | 1000 |

1200 | 1400 |

1600 | 1800 |

2000 | 2200 |

GMT | OOW |

0000 - 0400 | 2nd Mate |

0400 - 0800 | 1st Mate |

0800 - 1200 | 3rd Mate |

1200 - 1600 | 2nd Mate |

1600 - 2000 | 1st Mate |

2000 - 2400 | 3rd Mate |

When I go off watch a kind of robot, which was probably designed by "No. 5" or "Wall-E", takes over from me and keeps watch until I return. This robot is an Auto-Alarm whose name is "Seaguard" and it listens out for a radio telegraph alarm signal. If it receives one it triggers off three big bells , one in the wheelhouse, one in the radio room and the other above the R/O's bunk in his cabin - "would you like a wake-up call Sir?".

When I was being trained and on other ship's that I had sailed on previously, the Auto Alarm types were filled with banks of electro-magnetic relais and not so many valves but the "Seaguard" was a clockmaker's paradise. To get it running, you had to logically switch it on first to power-up the electronic parts but then came the real fun bit - trying to switch on its engine inside its "engine room". The front panel of the A/A had a glass window behind which you could see a contraption that looked like something you might see in a SF movie. Its main component was a beautiful looking shiny brass coloured centrifuge which you had to get running with the aid of a metal spring-loaded spindle which protruded through the front panel above the window. You had to grip the spindle between thumb and forefinger and pressing it inwards give it a flick to get the centrifuge started with enough power to overcome its inertia and hopefully start spinning. It had a mind of its own, machine versus man and it could drive one to despair sometimes whereas at other times a single flick of the wrist would get it going. I found out later by experience a way to help it start!

Since leaving Elbe 1 behind we have been passing the German islands Wangerooge, Spiekeroog, Langeoog, Baltrum, Norderney, Juist and Borkum on our port (left) side. On the Dutch coast this island chain continues with Shiermonnikoog, Ameland, Terschelling, Vlieland and Texel. This last island almost touches the mainland at Den Helder.

When I go on watch the first thing I must do is take a traffic list from Portishead Radio which is the main British coast station, like Norddeich Radio is for Germany. It is compulsory for R/O's to record the list being transmitted into the radio logbook which is officially titled the "Diary of the Radiotelegraph Service". It had five columns with headings from left to right:

Date and Time (GMT) / Station From / Station To / Full Details of Calls, Signals and Distress Working / Frequency.

I hated the logbook mainly because it was in Foolscap size which when spoken sounds just like it is written (designed by a fool to wear on his head). Foolscap was a British Imperial Measurement and its name originated from before the 18th century when this type of paper had the watermark of a fool's head on it (no joke!). It was 8" x 13" or 203 x 330 mm. It didn't have pages like a normal book but instead was like a "Rollodex" without the "dex". When a page was full you had to pick the logbook off the desk, fold the page you just finished up, back and then under the book. It's length was too long for the table. Anything we wrote on it had to be done with an indelible pencil whose "lead" was a blue colour and which had to be continually resharpened. You had to press hard with the pencil because a carbon copy had to be made through a blue "carbon", a sheet of which came with each new logbook.

Nearing the final blank pages of the logbook - the carbon sheet, like an old typewriter ribbon, was dying of exhaustion. Similar to the paramedics of today we tried to prolong its life by pressing harder with our special blue pencil but this only served in the long run in killing off our pencil sharpeners and blue pencils. Blue carbon paper? No problem - there was a fresh sheet with the next virgin logbook.

The logbook was the British government's "Black Box" for R/O's. Like the song from Perry Como went (or was it Al Martino? Al Capone? Dean Martin ?) "Catch a falling star and put it in your pocket" read instead "Catch a stupid Sparks and cruxify him". The logbook had to be countersigned by the captain once a week but for him it was like signing a blank check. The gibberish that he was supposed to read and understand before signing would have defied even the British Museum's cryptologists.

Back to the traffic list: GAAA GAAA GAAB GAAB GAAC GAAC GAAZ GAAZ GABA GABA GABB GABB - get the idea? Yes, each one is the radio callsign of a British ship transmitted twice in morse code and in alphabetical order. Only the callsigns of vessels for which Portishead has traffic for are transmitted (for an explanation of traffic - remember the GPO BSA Bantam motorcyclist knocking on your door and proudly announcing "I have a telegramme for you!").

The British ship callsigns which were Gxxx to Mxxx were transmitted from "Alpha to Omega" At least we only had to write each callsign down once but after they ran out of British ships, it started all over again with the callsigns of foreign ships. In a way this was o.k. by me because by the time they were finished the rest of my watch had been reduced by about a 1/4th!

The Weybank's callsign is GMHZ - in morse code this is transmitted as:

--. -- .... --..

The Morse Code is comprised of dots and dashes and there are rules on the length of a dot, a dash and a space. I won't bother you

with further technicalities except to say that we R/Os call a dot a "Dit" and a dash a "Dah"- like speaking in Hindi.

Spoken, GMHZ would then translate as "Dah Dah Dit Dah Dah Dit Dit Dit Dit Dah Dah Dit Dit " = two curries please and go slow on the chapaties.

When listening to morse on the main receiver I could change the tone of the dit/dahs with a control called the "Beat Frequency Oscillator", BFO for short which helped a lot in keeping our sanity.

Try and imagine how it would be like listening out for up to half an hour for your own personal Dit/Dah callsign combination in a traffic list without either being hypnotized or drugged into a deep sleep. No wonder most of us were chain smokers - we had to distract ourselves to keep awake.

To make matters worse my Foolscap logbook pages, as long as they were, were usually too short to accomodate a single watch's entries with all the traffic lists etc. and thus would rapidly start filling and become unmanageable - too much crap folded underneath and not enough "clean" page weight above. If you were right-handed, your left hand was hovering over or gently grasping the tuning knob of the receiver from which you were receiving from. It had to be because a ship is always in movement and even a slight judder could knock your receiver's electro-mechanical tuning "off tune".

As soon as the traffic list was over I chucked the logbook aside and anything I else I had to write down during the rest of my watch I wrote on a Marconigram message pad instead which was a nice handy kind of DIN A5 sized pad. I could then also use a Biro to write with instead of "Miss Marple's Favourite Colouring Pencil for Politicians".

At the end of a watch (or even a week later) I first scrutinized and then transcribed my "selected" message pad scriblings into the logbook in nice legible Miss Marple script - try and catch me Big Brother!

At the termination of our voyage after 15 months a "Superintendant of the Mercantile Marine Office" came aboard to officialy receive the radio logbook. In a ceremony reminiscent of signing the "Magna Carta", the captain's, my own and the inspector's signatures were signed on what could have been potentially my "Doomsday Book".

The deck and engineer departments also had their respective logbooks to fill and they

maintained them in the same way - as the German's say "Doppelt hält besser" - double holds better - the Captain would scrutinize the Deck Officers "scrap" logbook before it's contents were transcribed to the official logbook.

There were 22 explicit rules as to what had to be recorded in the radio logbook and I will get to some of them later.

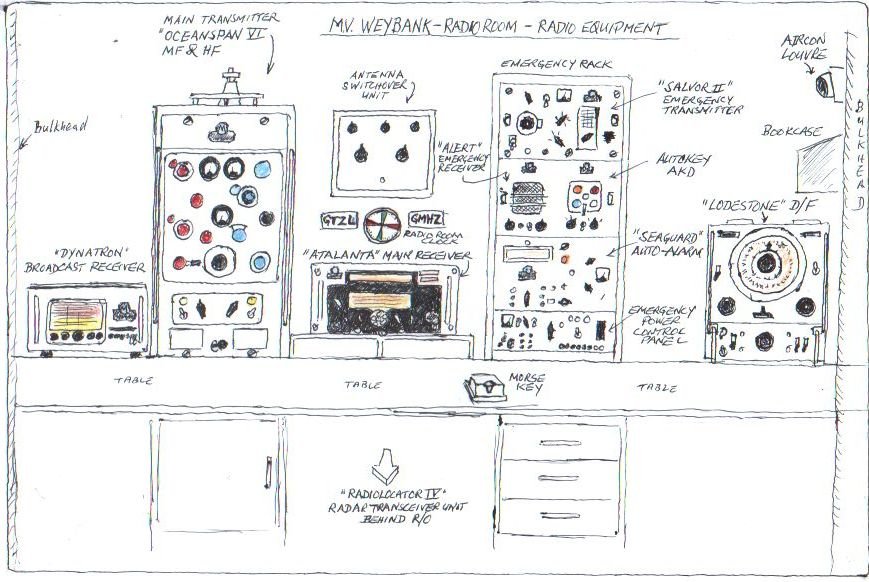

I had two rooms aboard that I could call my own. One was the Radio Room and the other was my cabin. At sea I spent on average eleven or twelve hours a day in the radio room.

Me "posing" in the radio room of the Weybank but the 2nd Mate steals the show, as usual. This photo must have been taken after we had already been aboard for well over a year because I can see a map open on the table with Korea and southern Japan showing on it. We headed for Japan after leaving Taiwan.

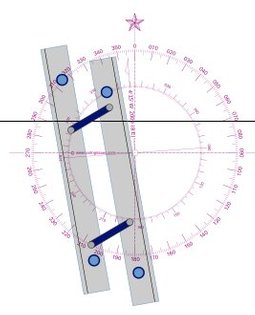

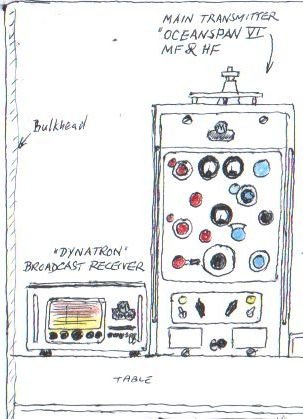

I will give you a short guided tour of it with the aid of a sketch I made but first here is a list of the equipment which was my responsibility to maintain:

Oceanspan VI DC Main Transmitter (no Radio Telephony -R/T)

A1 A2 M/F 410, 425, 454, 468, 480, 500, 512 kc/s

Power 0.1kW (100 Watts).

A1 = Continuous Wave - CW

A2 " Modulated Continuous Wave - MCW

A1 H/F - a number of spot frequencies on the 4, 6, 8, 12, 16 and 22 Mc/s bands.

Salvor II Emergency Transmitter

410, 425, 454, 480, 500, 512 kc/s A2 25 watts

Antenna Switchover Unit

This unit is used to connect the Main or Emergency Antenna to either the

main or emergency transmitter or to earth the antennae in case of a severe

electrical storm or to discharge static build-up.

Salvita Lifeboat Transceiver.

500, 8364 kc/s A2 5 watts

Atalanta Main Receiver

Alert Emergency Receiver

Seaguard Auto Alarm

Autokey AKD (Automatic Keying Device)

Emergency Power Control Panel

Two seperate 24V DC banks of heavy-duty large lead-acid accumulators

These comprise the Emergency Supply for the radio equipment and are contained

on two deep metal shelfs inside its own battery locker room behind the radio room.

A unit used in charging these batteries called the Charging Mat was contained in a large metal box above the companionway leading to the bridge.

Lodestone D/F

Dynatron Broadcast Receiver

Seagraph wet paper recording echo-sounder unit

The Seagraph was installed in the chartroom - its underwater acoustic "antenna" called

a Transducer was built into a recess at the bottom of the ship's hull.

Argonaut VHF Transceiver

Radiolocator IV Radar

Starting from the left we have the MIMCO "Dynatron" Broadcast Receiver.

The audio output from this type of receiver (RX - I will call a receiver by this abbr. in future) was fed via cables to loudspeakers in both the officers dayroom and the crews messroom. The "Dynatron" was originally installed in ships messrooms so that the crew could tune-in themselves to whatever turned them on at the time. However, either the music they were listening to or whatever they were drinking and/or smoking seemed to induce a kind of tribal aggresiveness against the poor Dynatron. At the least it was danced upon and at the worst ripped from the table and chucked over the wall (the ship's side, into the drink).

This became expensive for the shipping company (not for MIMCO because they could sell Dynatron's replacement) and so eventually it was decided to install it in the radio room.

Aboard the Weybank we had no telephone system (apart from voice pipes) and so the result of this madness was that crew member "A" wanted to hear the BBC football results immediately whereas crew member "B" couldn't get to sleep before his watch because the loudspeaker was blaring away down the alley way. Up they would come - "Sparks - knock that shit off now, otherwise!" - "Sparks, can you get "Diana Ross and the Supremes? - Joe in the cabin next to me has got it right now with his Panasonic on shortwave but he won't let me in".

To make matters worse, the Dynatron did not have a loudspeaker. I had to plug-in my headphones, stick them over my head and try and position the earpieces over my ears so that I could hear something other than "Wey Ay Man - Party's On! - Git us "Eric Burdon and the The Animals"".

I could have spent the rest of my life like a mad disk jockey in front of Dynatron but I killed him instead. Yes, I pulled his plug.

"Sparks - the Dynatrons not working, we've got no music"

"Yes, I already know, he died last night with a flash and a bang and before you ask, there is no chance of me getting replacement parts before we reach Timbuktu "

"Are we going to Timbuktu?"

For some, all was not lost - quite the opposite - the Weybank's generators generated 220V DC - not much use for 220V AC electric shaver or portable Grundig/Panasonic type "boom boxes". This is where Dynatron's support system came into its element. It was a "Static Inverter" in the form of an elongated box which magically, without noise, transformed 220V DC to 220V AC. Poor Dynatron had been hooked off its life support system but this system transfused its energy via wires crawling from it like jungle lianas all over the vessel to the Captain's, 1st Mate's, 2nd Mates, xxxs' cabins to

give life to their electric shavers (a fairly new fangled invention of the time).

To the right of the Dynatron is the "Oceanspan VI" Main Transmitter:

This was the main transmitter and covered the Medium and High Frequency bands. The MF frequencies centered around the International Distress Frequency of 500 kc/s. Typical spot frequencies were 512 454 480 468 425 Kcs for traffic and 410 Kcs for D/F. For HF long distance communication, frequencies were centered on the internationally allocated marine bands on 4 6 8 12 16 and 22 Mhz.

The dials and selection switches used for tuning etc. on HF frequencies were all red coloured; the controls in blue colour were for working with MF frequencies. Black switches and dials were "neutral" and used for both MF & HF. The two meters at the top indicated power output to the antenna whereas the one in the middle was used to monitor the functions of various valves inside.

Apart from its woeful lack of power, the only really annoying thing about it was the noise racket it produced when transmitting. This was caused by the rotary converter which converted 220V DC into 700V DC for the power amplifier (PA) valves. When the morse key was "up" the TX was in a "comatose" state but as soon as the key was pressed down the PA started "loading" the converter (like a beast of burden) and it started to complain audibly with a loud kind of "whey"/"whee" noise. As soon as the morse key was lifted, transmission ceased and the converter purred away almost in silence.

To make matters worse, Marconi radio station installations did not have what was called a sidetone generator. When a morse telegraphist presses the key down to transmit a dash for instance, he doesn't hear the dash being transmitted. Instead he hears a click when the key is pressed down at the start of the dash and another click at the end of the dash when he has lifted the key up. When transmitting to a coast station, I would transmit on an allocated ship frequency and listen to the coast station on his allocated frequency with the Atalanta main receiver via its loudspeaker. However, as soon as I pressed the morse key the receiver would cut-off automatically but as soon as I lifted it again reception was restored. What was happening here was that the the Atalanta's receiving antenna was being disconnected to prevent the energy that was being transmitting from my TX antenna

from literally burning out its input circuits.

The cacophony generated was not in sync with the morse code being transmitted. There were many R/O's who had not been trained to transmit "blindly" and could not cope with this and therefore had to use a sidetone generator which produced the morse code being transmitted in audio form which could be heard on a loudspeaker.

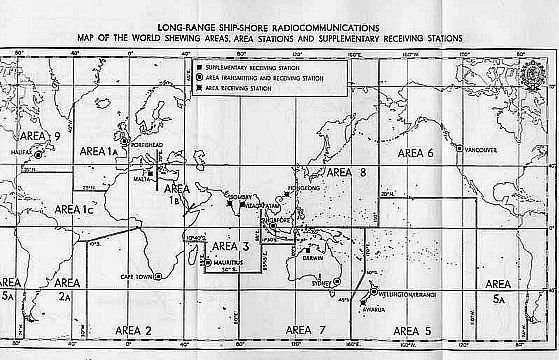

Concerning the low power output - the British had a an Area Scheme which consisted of radio stations sited at geographical locations throughout the world. There were eight main transmission stations, among them Halifax in Canada, Capetown SA, Mauritius, Singapore, Sydney Oz and a total of fourteen altogether. I often used Mauritius, Singapore, Sydney and a few others myself on the Weybank. Traffic I had for the UK but sent to an area station would be either retransmitted by them with more powerful transmitters or routed via cable. Even with only 100 W transmission power I could though usually make direct contact with Portishead but it meant me getting up in the middle of the night to do so when the atmospheric conditions for long distance communication were at a peak.

A few nations such as the Dutch used some cargo vessels as retransmission stations for Dutch ships but otherwise foreign R/O's were mainly expected to make direct contact. This is why the transmitters aboard foreign vessels were much more powerful than their British counterparts.

All transmission on HF with the Oceanspan VI was by Continuous Wave (CW) A1 mode. The Oceanspan was a well built and very reliable transmitter. In all my time aboard the Weybank I cannot remember having had any malfunctions with this transmitter. I did preventive maintenance on it and remember cleaning the collector of the built-in rotary converter and replacing the collector's carbon brushes but I never had to repair this TX (transmitter).

To the right of the Oceanspan VI we have the Antenna Switcover Unit, Radio Room Clock and the Atalanta Main Receiver:

The Antenna Switchover Unit's (ASU) main function is to switch either the Main Antenna or Emergency Antenna to either the Oceanspan VI (Main) or Salvor II (Emergency) transmitter. A Dummy Aerial can also be selected for testing either of the transmitters transmissions .

For further information on this function I highly recommend the New York Times bestseller: "Dummy Antennae for Dummies".

Below the ASU is the Radio Room Clock - synchronized with the aid of a key and my finger to GMT. This clock is my real boss aboard ship. Everyday I must slavishly look into his white, red and green face and obey what he shows me.

I don't really have to bother about his green coloured scar but I must be very wary of his red Cheshire cat's grin. I will tell you in due course bit by bit about how important time is aboard a ship and my part in keeping the ship "on-time".

On each side of the clock there is a plaque. On the left is GTZL, the collective callsign of the Bank Line and on the right, GMHZ - Weybank's, my own callsign.

The "Atalanta" Main Receiver is our gateway to the world beyond. I receive

via this receiver (RX) orders from the shipping company or our shipping agents, weather (WX) reports, navigational and safety warnings (TTT), long distance (HF) correctional information for our navigators to keep their navigation/sea charts up to date, correctional information for my own volumes of the Admiralty List of Signals, the results of football matches Saturdays - especially the football pool, private telegrammes for crew members ("Dear John, I don't know where to start but I know you will understand, you being away most of the time..." or on happier

occasions "Congratulations! You have just become a father! She is a lovely

little...").

Via this receiver we learn what is happening throughout "The World" which

we ourselves would otherwise have lost "normal" contact with.

Any crew member that had bought a "World Receiver" usually had a hard time trying to privately keep track of the world beyond. There were many reasons for this, the first and foremost being that they would not function with the DC supply from the Weybank. They had battery compartments that fed on six or eight "torch batteries" at a time - "supply and demand" - you couldn't just walk down to K-Mart and get another box full and if you could, they were not cheap to buy either.

A receiver needs an antenna otherwise it cannot receive! Some intelligent crew members thought "Mmm - there are plenty of

Sparks's antennas up there, I'll just hook on to one of them with my very thin dark coloured insulated wire that I specially bought for this purpose before sailing - he'll never notice". Well, I always did notice and on more than one occasion I told the culprit " You have half an hour's time to remove it, otherwise!" "Otherwise what?!" "Otherwise I will blow your "Ocean Boy" into the ocean - at the moment he is connected to my emergency transmitting antenna!"

Returning to the "Atalanta" - this was a very good receiver and as with the Oceanspan I never had to repair it - it never failed me.

My two most trusted companions!

At this point, before continuing with the "Emergency Rack", I will tell you a little bit about how much we were isolated from the "British Way of Life" in the UK during almost all of 1968 and half of 1969. The year 1968 remains embedded in my mind with the "TET" offensive in Vietnam, not because of the actual offensive itself but because it blew the lid off our youth's society.

On my previous ship I remember listening on watch (bad boy) to "California Dreaming", "If you're going to San Francisco be sure to wear a flower in your hair", "Everybody's goin' surfin". I can't remember when "Woodstock" was but for me it was all the same thing - "Free Love - anytime, anywhere!". I thought to myself : "What a pack of degenerates - no self discipline - a bunch of hippies trying to control the world who themselves are not even out of school yet" . I despised them not only because they had not apparently experienced any of the kind of hardships that I was accustomed to but had not experienced any kind of hardship at all! (Nowadays

I would be happy if I could have joined them).

I think that the longer a voyage took, the worse this kind of "elitist thinking" became - we were not being held captive by any human entities but by ourselves within our own ever advancing spaceship. Many years later I became a fan of TV re-runs like, "Fawlty Towers" or the music hits of Linda Ronnstadt or ....... During my times at sea I had never heard of any of them. When finally back "home" at some later date, some later time : "You don't know who Basil Fawlty is?! - Unbelievable! You must at least know Manuel - "Sorry, Mr. Fawlty"!"

What we did gather on our spaceship was a profound understanding? of human nature and of the beauty of the seas around us; the earth, flora and fauna that we could literally smell when approaching another destination - the breath of life!

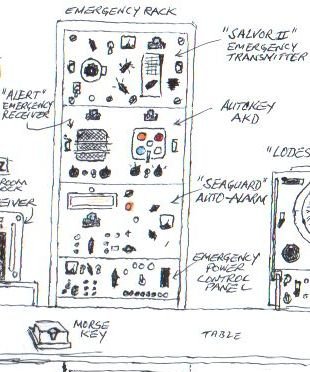

Last but not least: The Emergency Rack

Everything within this rack is supplied by the radio station's

Emergency Battery supply i.e., Lead-Acid accumulators.

If you own a car you know what happens if you don't look after your

battery - it won't start! So, what do you do? Get your wife out of bed

to push it while you expertly manipulate the ignition key; wake the

neighbour up and ask him/her if you can connect your jumper cables;

the list is endless.

Aboard the Weybank if the batteries ever become flat - I can hang myself

to get it all over with quickly. The two banks of batteries which we carry not

only supply the emergency rack equipment but also supply units of the

main equipment. When one bank is being used, the other is being

recharged for use the next day. I mentioned the Radio Logbook

previously but we have other logbooks to maintain and one of them is

the Battery Logbook. I must record specifics of each battery's cells

every day. I must regularly go into the Battery Room/Locker and, like

a doctor, take each battery cell's "temperature" but instead of a thermometer

I use a Hydrometer and instead of temperature I measure "Specific Gravity".

I told you that I was aboard a kind of spaceship!

Now to the top of our rack/list: the "Salvor II", the Emergency Transmitter.

"Salvor I" probably died fighting in battle but "Salvor II" was quick to pick up the sword and protect us further. The name "Salvor" always

brings to my mind the Salvation Army who valiantly fight to save the downtrodden. To give you an idea, this happened to me a few years later: beautiful day, early afternoon, sailing tranquilly south-westwards past the Azores - I'm on watch dozing about as usual when suddenly all the radio equipment "died". Sudden death - no pieps - no "dit dah" - silencium total! I then became aware that the "background noise", meaning the engine reverbrations and resultant ship vibrations had also died. We had really become like a spaceship moving silently through space.

The main generator had failed but even worse the "Lecky" (the Electrician Officer) could not get the emergency generator to start. This is "Dark Vader" all over again - no electricity means a light switch cannot produce a glow, a cooker cannot produce hot food, refridgerated food starts dying (our food), everything aboard run by ship's generator electricity has died a quick death or is in the process of dying fast.

"Time is money!" - we are transporting automobiles to the west coast of the USA. We are on a time charter - if we arrive on schedule, everyone aboard gets a "piece of the pie" - a monetary bonus! Every second or minute counts - "Hours? are you mad!?!"

The time has come for me to send an "XXX" message to the Azores where there is at least one (mainly Dutch) ocean-going salvage

tug waiting like a shark for just such a victim. An XXX is an Urgency message and is in the hierarchy of message priority just one step lower than an SOS. An XXX message is sent if a ship becomes unmaneuverable like we had or had damaged steering gear or to call for urgent medical help from a doctor etc. The captain must make the decision whether to send or wait. If a salvage tug is called and hooks us up it will cost the shipping company a hell of a lot of money, on the other hand we cannot float about like the "Marie Celeste" for ever.

This is also for me the "Moment of Truth" - when did I last charge the batteries? On this ship there is only one bank of batteries so there is no back-up bank to switchover to. How long would the batteries last when I started transmitting?

To end the suspension, I did not have to transmit the XXX because after floating helplessly about for six hours the Lecky managed to

get the main generator running (but not the emergency generator). On the one hand I was saying my prayers but on the other I was a bit disappointed because on my last ship (an oil tanker) we had put into Ponta Delgado in the Azores and I wouldn't have minded paying another visit (that was where we berthed just ahead of a Deep Sea Salvage tug).

I wrote the above to let the reader know how at sea danger could occur at any moment and very often when least expected. If our ship's generators failed, the only way I could get help was by transmitting with the Salvor II and receiving with the Alert Emergency Receiver.

There was one more possibility - if we had to abandon ship we had a Lifeboat Transceiver!

The Salvor II transmitted on mode A2 with a meagre 25 Watts of power. Another word for A2 was Modulated Continuous Wave or MCW.

A2 was a mode whereby a receiver which is only designed to receive telephony (speech) can receive this A2 mode of morse transmission, provided it could also be tuned to 500 kc/s and that the operator could understand the morse code. Ships equipped only with radio telephony kept a continuous watch on the telephony International Distress and Calling Frequency of 2182 kc/s. If I therefore had to transmit an SOS there was not much chance of getting help from a telephony ship unless we were for instance in the English Channel and he had been informed of our distress via a coast station. Nonetheless, for this reason (that maybe a telephony station could pick up our signals) if we had to transmit a distress signal, it had by law to be in mode A2 (which incidentally only has a quarter of the power of an A1 CW signal).

The Salvor II had its own built-in morse key and I could transmit very fast and clear morse with this key even though I had to do it standing up. I found that I could trim it like a "bug" key (a very sensitive morse key type) and many times I heard from other R/O's that they thought I was using one.

The Alert Emergency receiver comes next. This receiver could only receive on 500 kc/s and on mode A2 and that there is not much more to say about it except that it wasn't exactly the "Rolls Royce" of receivers, more like a "Morris Minor Minus". If I was operating with the Atalanta main receiver on HF, I had to keep a second ear listening to the Alert (as soon as I tuned the Atalanta to any other frequency apart from 500 kc/s I was obliged by law to listen also on 500 kc/s).

The Autokey AKD sited to the right of the Alert is a unit which was designed to enable cowardly R/O's to almost immediately vacate

the radio room and if possible the ship in the event of the vessel sinking. Well, a few of them might have been cowards but I never heard of one. R/Os like captains are the last to leave a sinking ship. They both try to prevent the unavoidable and in the case of the R/O he knows he has to morally stay until he either makes contact with a salvor or until the radio equipment fails or the ship starts breaking up and starts to go down. He knows that if he cannot contact help while aboard the vessel, the chances of survival once aboard a lifeboat are for all of them greatly reduced. I will tell you about the capabilities of the lifeboat transceiver in due course!

As a prelude to the the Autokey's function:

If a vessel is sinking, the ideal way for it to do so would be with an even keel, i.e. to sink slowly and in its normal "upright" position. If this were the case then it would mean that sea water had broken into the vessel and found its way through a number of bulkheads, filling up the vessel like filling a glass of water.

I once saw a ship go down like this. It was an old Italian freighter called the S.S.Allegro which was carrying a cargo of iron ore. There are ships called Ore Carriers which are specially built for this purpose but the Allegro wasn't one of them. It was just an old tramp ship with the main accommodation and engine room midships.

Iron ore is a very heavy cargo and because of this a ship's hold can only carry a relatively small amount compared with other bulk cargoes. Another danger was that if this type of cargo shifted in the hold due to for instance bad weather, the ship would take on a list and there was no way she was going to right herself again, the list could only get worse not better.

This was however not the case with the Allegro - she was going down on an even keel in rough weather. On our way from Aden to Bombay in the Arabian Sea our vessel picked up an SOS from the Allegro and we were the only ship close enough to help in time. We had to turn back and steam for eight hours before we reached her in the middle of the night. The crew of the Allegro had been fighting for over 12 hours trying to save her but to no avail and when we arrived they took to a single lifeboat which they managed to lower.

The sea was very rough and the crew had to try and stear and row towards us. A big ship such as ours was is very difficult to manoeuvre in such conditions and the Allegro's lifeboat whizzed passed us twice, failing to grasp the lines thrown out to her. On her third and what would surely have been their last attempt because they were all exhausted they managed to hold the line and more that then followed. We had a cargo net down over the port side where the lifeboat now alongside was rising and falling like a non-stop up/down mad hotel lift.

Each crew member had to judge the moment when the "lift" reached its apex and then spring from the lifeboat to the net and then start climbing as fast as he could to prevent the lifeboat's next "rise" from crushing him between the lifeboat and our vessel. In this way all the crew were saved except for one poor soul who misjudged his jump fell to the sea below where he rapidly disappeared aft out of sight into the night.

We stayed on station circling the Allegro at a distance - it wouldn't have been the first time that a vessel refused to sink but slowly she continued to sink on an even keel. I saw a remarkable sight which was that her midship accommodation lights were still glowing although that section of the accommodation was already underwater. Finally after an hour more she finally surrendered to the sea and

with heavy hearts we changed course and headed once again again to Bombay.

Returning to the Weybank - the boring "technical" radio stuff having been covered - we sailed through the English Channel without mishap. It is always a dangerous area with at any one time many ships sailing in both directions east to west and west to east and with cross-channel ferries traversing from Dutch, Belgian and French ports to English ports and vice versa. Add to that a large number of "weekend sailors" (yachtsmen) and a potential disaster is always looming. I sailed through the English Channel many times and in nearly all instances I can distinctly remember the XXX calls from French, English, Dutch and Belgian coast stations warning "all ships" to keep a lookout for a missing yacht . In some cases the "missing yacht" turned out to be not missing at all but was tied up at some cosy Marina while the crew were chatting up the barmaids at the local pub.

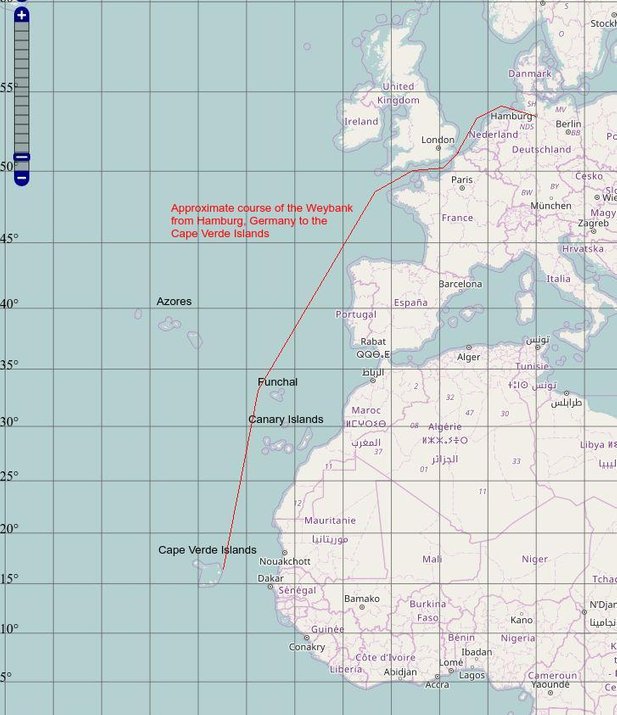

I would listen to the continental and English commercial radio stations and also to the "Pirate" radio stations such as "Caroline". As we left the English Channel behind, these broadcasts became fainter day by day but could still be heard at night. Instead the broadcasts from Portuguese commercial stations became stronger as we passed the Portuguese coastline to port and sailed closer to the Azores. The music transmitted from the Portuguese Azores was usually sad and melancholic - there is a Portuguese name for it called Fado which comes from the Latin word "fatum" meaning fate: the inexorable destiny that nothing can change. I have a link to a video in this website's Video section of Ana Moura, a famous contemporary Portuguese singer singing Fado. I listened to Fado every day until once again we had travelled too far south to pick it up. Further south we passed the island of Funchal which is Portuguese and then the Spanish Canary Islands ( from which I could listen to Spanish music until they also faded away beind us).

The sea chart shown below is a screenshot from the website "map.openseamap.org" in which I have included the approximate course of the Weybank and labelled the Azores, Funchal , the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde Islands (zooming in on any of these islands on the OSM website shows their names and details just like Google Maps).

On the chart above, if you look to the right of the text written in red you will see the infamous Bay Of Biscay. When passing west of the bay our 2nd Mate lost all of his teeth , not by getting them punched out by an irate seaman but by a single "barf".

"Barfing" is slang in the UK for "violently emptying the contents of the stomach" and is a kind of "badge of honour" for a lot of UK teenage pub-crawlers on a Friday &/or Saturday night (stagger out of the pub if you can make it on time and then "barf" all over the street or anyone standing in the way, preferably a cop, male or female).

The 2nd Mate is not to be blamed for any such bad behaviour - he barfed honourably!

One of the greatest fears that a seaman had aboard a ship at that time was that of becoming violently ill or injured. There was no doctor aboard - a cargo ship which had more than 12 passengers aboard had to carry a doctor as a crew member which is the reason why most cargo ships didn't - too expensive for the shipping company.

There were no satellite communications or "hotlines" as today. There was an ANVER system for the North Atlantic to keep track of vessels and a radio station in Rome for obtaining medical advice (by Morse key "Permiso, parliamo Italiano?"). The only other way was for me to transmit an Urgency "XXX" signal over Medium Wave on 500 kc/s which had a daytime range of only approx 300-500 sea miles depending on atmospheric conditions. An XXX is a signal to all ships that are close enough to hear it and is just one step down in priority from an SOS signal. If a doctor is urgently required, I send an XXX in the hope that a passenger liner (by law they must carry a doctor aboard) is in the vicinity. If there is , a rendezvous is set up (Je t'aime mon amour) and both vessels navigate towards each other.

When the two vessels meet ( and hopefully not collide - usually the weather at such instances follows Murphy's Law), either the passenger vessel lowers a lifeboat with the doctor aboard or our ship has to lower one and then fetch him. Whichever the case the doctor is not very happy - his semi-cruise has been disturbed . His normal duties involve consoling and stroking the brows of multi-millionaire widows (in the hope that one will marry him) , pretty nurses (if they let him), drinking gin & tonic watching the sun go down etc. Now he has to collect his gear and be lowered down in the lifeboat (or, horror, the lifeboat is already down and he has to climb down the pilot's/Jacobs ladder to get anywhere near it). He probably, being a doctor, wasn't a fitness freak in the first place and so these exertions are already taking a toll on his own health. Hopefully he is not prone to sea-sickness because if he is he will be of no further help to anyone. If the seas are rough, he has to climb the pilot's ladder of the patient's ship (the use of the lowerable gangway ist too dangerous). Once aboard, providing he can still stand on his own feet, he is led to the patient. He definitely doesn't want to take this patient back with him but if his condition merits it - he has to. How to get a stretcher patient down into the lifeboat and once alongside the passenger ship up into it, I will leave to your imagination.

The 2nd Mate, Gordon (a fine Scots name, if I may say so), was a Scot from I think Dundee. He was married with two children and I guess he was around 30 years old at the time. He had been in the merchant navy since he left school and had been at sea a long time before joining the Weybank but he had one great fear - toothache at sea! There is not much worse than suffering a toothache which not only gives no respite day after day but instead increases in intensity. If you are ashore eventually you go to a dentist. At sea there is none to go to apart from the 2nd Mate. Gordon, being a 2nd Mate, is our ship's "Medic" like in the new movie "Hacksaw Ridge". He has been trained in the rudiments of how to recognize certain illnesses and apply their antidotes, how to splint a broken leg , how to dispense an aspirin against toothache.

On his last leave before joining the Weybank (navyspeak for vacation) he decided to put an end to his fear, went to the dentist and got them all extracted (dentist speak for "pulled out"). He could now fearlessly go back to sea.

I had suffered sea-sickness, "Mal de Mer" only once in my life when I was very young crossing the Irish Sea. I almost had it again about 40 years later when I was aboard a small fishing trawler off the coast near Pula , Jugoslawia (now no longer a nation). It was only then that I fully comprehended what Gordon had suffered.

Most seamen don't suffer from sea-sickness - if they did they couldn't/wouldn't stay for long but many seamen suffer a short spell of it when going to sea again after having been on leave ashore for a month or so and Gordon was one of this ilk.

During the "Middle Watch", 0000 - 0400 GMT - the "Middle of the night" -and passing the Bay of Biscay, Gordon started to feel a bit "under the weather" and this feeling rapidly got worse. Being a true gentleman and therefore not wishing to mess up the ship, he galloped to the starboard bridge wing and "barfed" over the side, forgetting that he had only a loose set of new "prothesen" which promptly accompanied the barf into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean.

Poor Gordon can now only ingest ("eat" is a different experience) semi-liquid fuel for the next six months or so. I had to transmit a telegram to his wife informing her to go to his dentist and arrange for a new set of teeth to be made and when they were ready to forward them by mail to our next port of call. Our ship may be slow (approx. 19 Knots speed) but the mail is much much slower. As our next viable port was Durban SA, I sent a telegram giving our Durban shipping agent's address to Gordon's wife. By the time the teeth arrived in Durban, we had already left Karachi in Pakistan - and so the teeth followed the Weybank like PacMan - munch , munch, munch, (port, port, port).

When after about half a year they finally caught up with Gordon, they didn't fit properly ("pop by our praxis when you have time and we will make a few adjustments, we might however have to send them back to the technicians who made them").

Goodby Europa, until we meet again?

End of Chapter 1