Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 14

The Philippines (continued from Chapter 13)

Because Copra for certain insects is like a yummi-yummi Big Mac, they already delve into the jute sacks stored in the warehouses. When the jute sacks are hauled aboard by our derricks they contain not just Copra but also a load of insects excited about their upcoming cruise. The sacks contain cockroaches, spiders and whatnot but the nationality of the main passenger group by far is that of the Copra Bug.

As far as I know there are two (or maybe three?) species - black ones and brownish coloured ones but one thing I know for sure - our unwanted guests were black ones. I don't know if about a million of them arrived aboard in the sacks but like most species on this planet apart from eating they liked having sex - so much so that they must have been "gang-banging" most of the time. The biggest of them was maybe only about a centimeter long - about the length of your pinky-finger and they looked kind of cute as far as beatles go but they invaded every nook and cranny aboard. I would occasionaly get a nip from them as they mistook me for copra. They landed everywhere and seemed to enjoy your meals as much as you yourself did. My daily curry rice was speckled with them as was the curry sauce. A few of the more squeamish of our officers at first tried to pick them out bug for bug but like the movie, it was Mission Impossible. As for myself, everyone knows that most insects are nutritious - at least that's what the Thai bar girls demonstrated when munching away from paper bags full of what I thought at first were chocolate chips.

The day came when we were fully loaded ready to depart - our derricks resting in their stowed positions and the hatch covers laid, covered with tarpaulin and battened down. On that morning I had stepped out of the accomodation aft onto the maindeck. I was distracted by something and turned to face forward in the direction of the accomodation which I had just left. I thought at first " who the hell has painted the white bulkhead black?" until on closer inspection I realised that it was not paint but instead maybe up to a million of our little black friends.

Our salvation, which still took a long time coming lay in the fact that at temperatures below 22°C they start dying. They also need a relative humidity of 50% or above to survive however, on our arrival in Hamburg much later there were still the "die hards" that would pop up just to remind us of what we were missing.

We finaly slipped our moorings and eased away from the pier. This time it was different and I felt a sadness realising that we were now in the process of leaving such countries as the Philippines, Japan, China, Thailand et al behind us for good but, at long, long last we were finaly homeward bound.

An afterword:

Many years later I would end up working in Iraq (during the Iran/Iraq war) and later still in the Persian Gulf states. In all of these countries it was (and still is) mainly Philippino women who filled the positions of hotel maids and receptionists, restaurant waitresses etc. etc. They were well sought after due not only to their good looks but especially due to their good education and that they spoke fluent English. These women generally had something like three year contracts and the lucky ones amongst them would get back home for a month‘s vacation during Ramadan when a lot of the restaurants closed down and alcohol was forbidden in the bars. For the rest of the year they worked their socks off and at night when they finished up at the restaurants they had to be transported back to the guarded camps/dormitories that they lived in by private secure transport to prevent them from being … well you can guess what. They saved every cent they made to send back home to their families. There were so many of them that worked abroad that the Philippino economy would have collapsed without them, that was how much money they were sending home.

I met a lot of these gracious and friendly women and admired them for their courage in their constant battle to keep their heads and those of their families above the poverty line. The Philippines have been since their independance controlled by a group of powerful land-owning families who manipulate elections and place their selected „our men in Havana“ in power positions. The birth rate and the resultant poverty is rising in leaps and bounds and those with no future turn to drugs. To top it all there is an all out war occuring around the south of Mindanao and in the Sulu Islands between the Philippino government and Islamic fundamentalists.

This year in 2019 the Jolo Catholic Cathedral was bombed by Abu Sayyaf fundamentalists which resulted in President Duterte ordering an "All-Out-War" directive against them. This led to heavy ground operations, massive airstrikes, artillery bombardment in surrounding areas, the evacuation of civilians in other areas and the creation of yet another infantry division - the 11th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army to bolster operations.

On the one hand you may think „Duterte again“ doing his Macho thing but in this case one has to take a close look at „Abu Sayyaf“. They have been for years kidnapping people all over the place and then demanding ransoms for their release – no ransom forthcoming? OK! Behead him! Even kidnapped youngsters as young as eight years old have been beheaded when the ransom was not paid. I have seen a list of persons held for ransom by AS over the past few years and it is LONG and the ransoms paid almost unbelievable. One candidate „for the chop“ was ransomed for over 5 million US dollars and he wasn‘t any famous movie star, industrialist or what not. Citizens in his country of origin managed to collect enough money from donations to save him.

However, in this world it is as the Good Book says - „The innocent shall suffer for the guilty“ - those on each side of a religious (or other) divide that just want nothing more than to live their lives in peace.

A recent and disturbing „farewell“ photo of Philippino troops mopping up „down south“:

____________________________________________________________________________________

Homeward Bound

The song "Sail Over Seven Seas" below (eat your heart out Stewart) could even have been sung by Donald (if we did something to him first) on our way homewards - it expresses how we all felt emotionaly at the time.

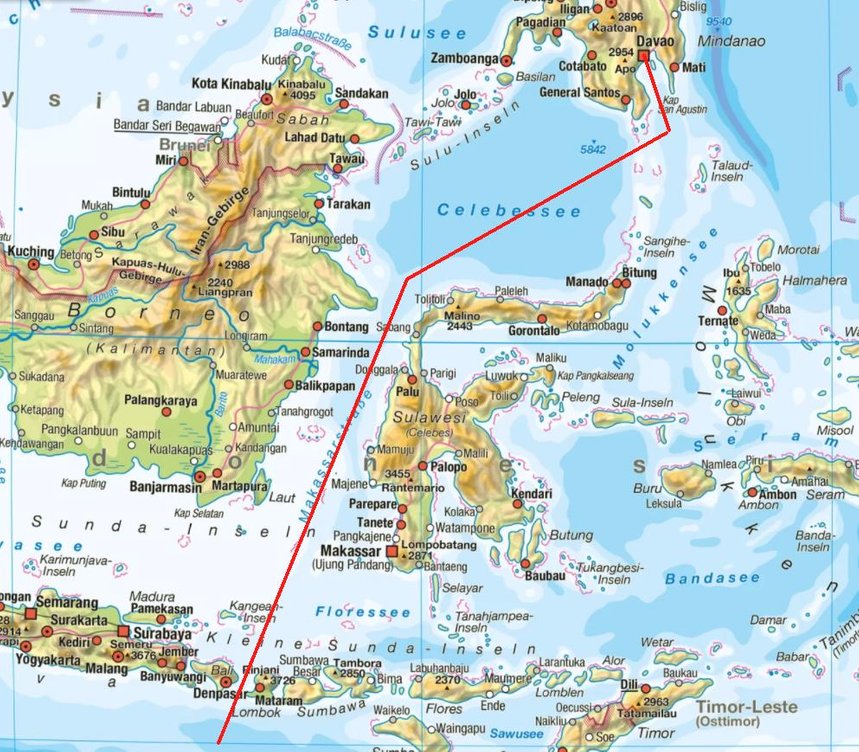

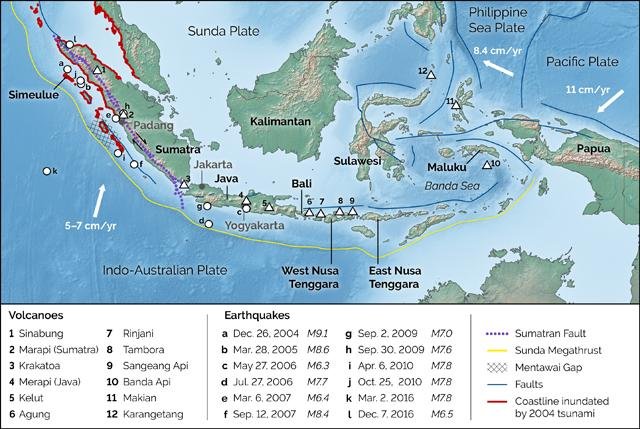

The red line in the map above shows our approximate course from Davao City to a point at 10°S 115°E just south of the island of Bali, Indonesia. The distance is 2359 km = 1274 sm and it takes us just over three and a half days sailing time. The gap between the islands of Bali and Lombok is called the Lombok Strait and we have to pass through it to break out into the Indian Ocean.

The island of Bali became famous from the song "Bali Ha'i" in the 1949 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific. This song conjured up all kinds of exotic „Bounty“ type fantasies although not many at the time had a clue where Bali was or if it even existed. A few lines of the song‘s text below:

Bali Ha'i may call you

Any night, any day

In your heart you'll hear it call you

Come away, come away

Bali Ha'i will whisper on the wind of the sea

Here am I, your special island

Come to me, come to me

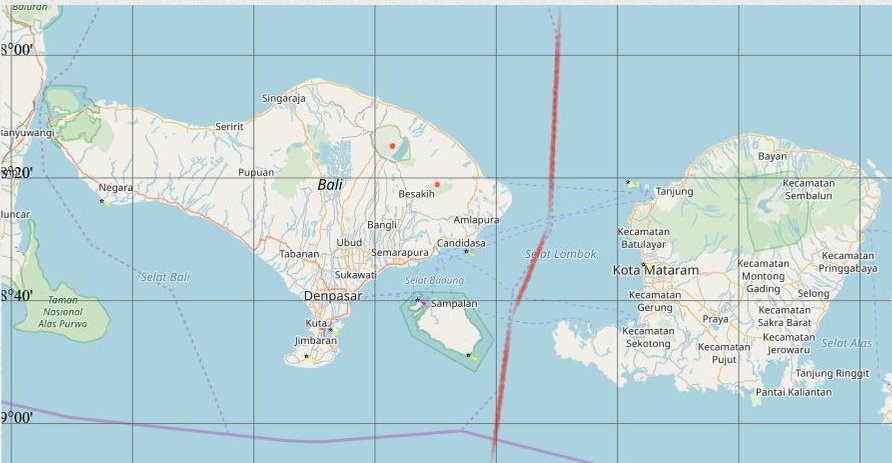

We entered the Lombok Strait on a beautiful sunny morning with a magnificent view of Bali to starboard. The Lombok Strait at our point of entry was only 20 sm in width and we were therefore only around ten miles from the coast.

If you have watched the „Sail Over Seven Seas“ video above you will recognize the photo below – it is one of the stills shown on the video.

This is the view of Bali that we had when entering the Lombok Strait. What you can clearly see are two volcanoes, both still active today. The one on the left is Gunung (mount) Agung (3031m) and the one to the right Mount Batur (1717m). The clouds above these volcanoes are caused by the heat rising from them causing condensation.

Just six years previously in 1963, Gunung Agung had decided it was time to "let off some steam“:

Mount Agung had been dormant for 120 years prior to its eruption in 1963 - it was Indonesia’s largest and most devastating eruption in the twentieth century and is estimated to have killed between 1,100 and 1,900 people in lava flows, mudslides, lahars and a deadly gas cloud in this and following eruptions which lasted almost a year.

The first eruption began on February 18 1963 and was followed by an explosive eruption on March 17 that produced a huge eruption column estimated to have reached heights of 19km to 26km (12 to 16 miles). This eruption lasted seven hours and generated deadly pyroclastic density currents, a fast moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter - and lahars (pyroclastic material debris) which devastated a huge area of Bali. People had just minutes to flee but many were incinerated when the gas cloud - which can travel hundreds of kilometres an hour - engulfed the area and further villagers were buried under mud or burned by lava. Cold and hot lahars rapidly formed in the torrential rainfall that followed the eruption and destroyed villages and constructions on the southern slope of Agung reaching all the way to the coast. This deadly eruptive phase was followed by small explosions, ash showers and pyroclastic flows which continued until a second more intense explosion occured on May 16. The four hour explosion produced a 20km ash column above the volcano summit.

Following this second explosive phase, the eruptions continued until January 27 1964 - almost one year after seismic activity first began - generally decreasing in intensity after the end of May 1963. Even so, this period was punctuated with larger explosive events and produced ash columns of 3km to 4km and an eruption column was reported to have reached as high as 9km on May 31.

After this dragon had finished it‘s year long roar of fire it appeared to go back to sleep again, maybe for the next 120 years. Unfortunately for the Balinese, in November 2017 the dragon woke up for a repeat performance but this time the Balinese were forewarned by its growling and evacuated around 100,000 residents from the area. Agung is still to this day erupting in fits and starts – according to geologist Diana Roman of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, it is impossible to predict what Agung will do next.

Above, Mount Agung erupting in November 2017.

As if this was not enough for the Balinese, we all know what happened in 2002. The Bali Bombings - an Islamic fundamentalist terrorist attack involving the detonation of three bombs that killed 202 people. While the majority of the victims were Australian (88), Indonesian (38), and British (28), people from at least 21 different countries were killed in the attack.

Returning to the Lombok Strait, thank you Agung for permitting us safe passage through your own „Pillars of Hercules“ (or Gates of Hell?).

Above, our course through the Lombok Strait (we somehow avoided bumping into Sampalan Island, maybe it was 3rd Mate Ken‘s eagle eyes that spotted it just in time, thank you Ken). The volcanoes positions on Bali are depicted by the two red dots.

A quick look around as we sail past:

Remember the lyrics to the South Pacific song?

Bali Ha'i may call you

Any night, any day

In your heart you'll hear it call you

Come away, come away

Bali Ha'i will whisper on the wind of the sea

Here am I, your special island

Come to me, come to me

I wrote a couple of additional lines (for which I expect any day now to get the Nobel Peace Prize for Literature, I mean if Bob Dillon can do it, it can‘t be that hard):

Bali Ha‘i is calling

Though we‘re tone deaf

Go away, go away

Whisper as you may

But we wont stay

We‘re on our way

Through night and day

Come what may

If you‘re so special

Put on your kettle

Let out some steam

To greet our team

Some lahars as well

To send us to hell

Or have some sense

And go f... yourself!

A propos the coincidence of the photo-still of Bali appearing in the „Seven Seas“ video – I wondered about that myself until I found out that both parents of the singer Tina T. (Tielman) were Indonesian – she herself was born in the Netherlands.

Time for one more song but this time it reflects on what I was thinking deeply about. The meanderings of the Weybank seemed to me at times to have only one purpose – slowly but surely to sever the thin thread holding Inge and I together. Through all the time we were at sea she had written to me and I to her but sometimes it took months for her letters to catch up with the ship and no doubt vice versa. When we finaly met up with each other again would it be as strangers?

What came to my mind as being almost divine intervention was that our destination port of call was Hamburg! What were the odds against that?!! Guess I‘m on my way:

Breakout!

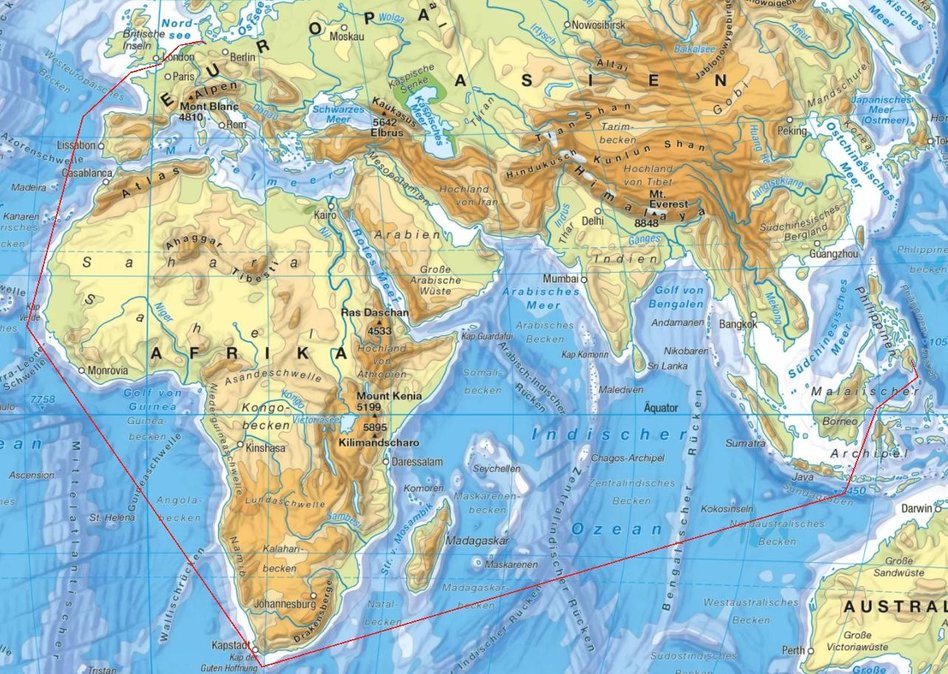

In the map above our approximate course between Davao and Hamburg is drawn in red.

The total distance covered by this course is 25129 km or 13584 sm, more than half the circumference of Earth at the equator. If we could maintain our 15 kt speed throughout it would take 38 days sailing time – over 5 weeks. However, bad weather and an overnight bunkering (refuelling) stop at Capetown would add to the 38 day estimate.

After passing through the Lombok Strait our next stretch to Capetown covers 10336 km or 5581 sm with an estimated sailing time of fifteen and a half days, just over two weeks.

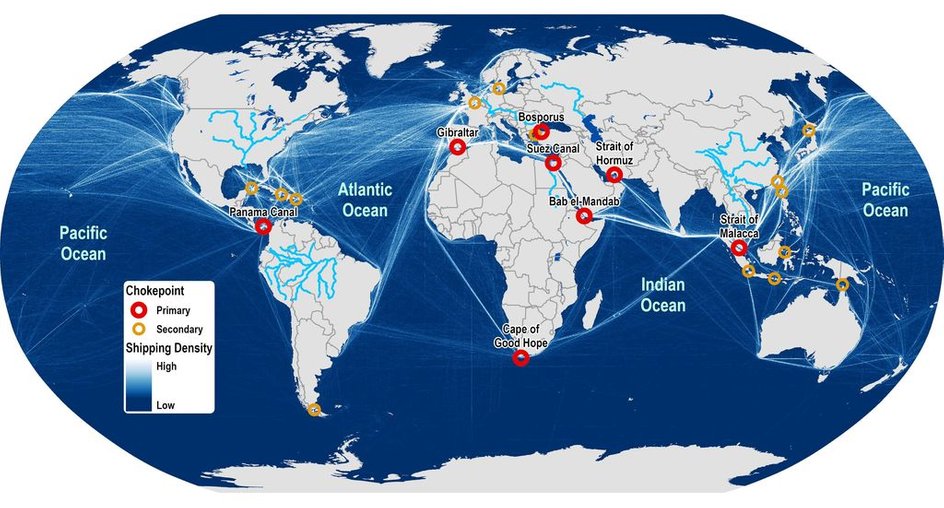

The global projection (2019) above shows the major maritime shipping routes and choke points. As can be seen the most densely travelled route, apart from the one through the English Channel, is that which passes through the Suez Canal to the Malacca Strait. Note the choke points - by the time we reach the Indian Ocean from Davao we have passed through two of them (both beige in colour). The first was between Borneo and Sulawesi (Celebes) at the Equator and the second was the Lombok Strait. If you drew a line from the Lombok Strait to the Cape of Good Hope you would see that it would cover neither a major nor a minor shipping route.

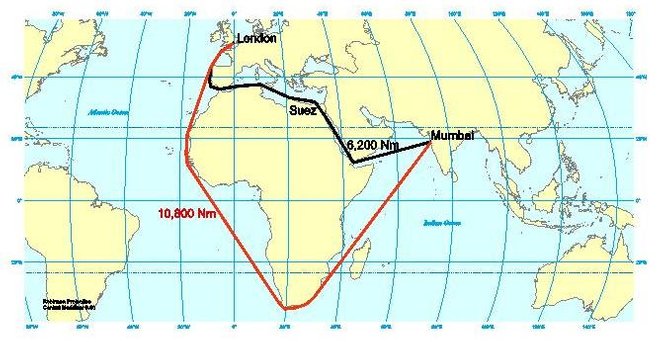

On 5 June 1967, at the beginning of the Six Day War, Egypt closed the Suez Canal. The closure was sudden and unexpected – fifteen cargo ships known as "The Yellow Fleet"' were trapped inside during the closure. At the end of the war, the Egyptian and Israeli armies were stationed on either side of the canal and the prospects for reopening were very uncertain. The canal remained closed until the end of a second conflict – the Yom Kippur War – and subsequent peace negotiations, eight years later in 1975. This was the reason why at the very start of our journey after leaving Hamburg we had to sail around the Cape to reach Karachi and also why we had to sail around the Cape again on our homeward bound trip. The map above shows the respective distances involved for a ship sailing between London and Mumbai (Bombay).

A few days out of the Lombok Strait we were well away from the normal shipping routes. If we got into serious trouble there would be in all likelyhood no other ships around that could have come to our aid. Normally at sea when I was on watch and guarding the 500 kHz distress and calling frequency, I could always hear the „chatter“ of ships calling coast stations (or vice versa) or ships calling other ships or coast stations announcing traffic, safety or weather reports. This „chatter“ ended abruptly, the only noise from my receivers being the crackle of static. This was when I started during the middle of every watch period to transmit an „all stations“ call on 500 kHz with the morse code for " CQ de GMHZ HW", just to find if there was any other ship around - no answer! (CQ = All Stations; de = from; GMHZ = Callsign of the Weybank; HW = How do you receive me?).

Before you could understand what happened next I will have to explain a bit about „static“ with respect to medium wave reception (500 kHz is a frequency within the MW bandwidth).

In days of yore you may have been listening to „The Goon Show“ for instance when all of a sudden there is a crackling noise on the radio. You immediately pop out of your seat and looking out the window say „Oh, it‘s Fred again escaping from his wife“. He had just started his car by causing sparks to flash over its spark-plug gaps. These sparks emit radio waves albeit unintelligable ones.

Static discharge can have many forms – one of the most impressive being lightning storms.

Generally, the closer one sailed towards the equator the more the static which could be heard on the radio receiver.

The total watch time that I had to do at sea was 8 hours a day however an R/Os watch period was 2 hours (not four as with the mates and engineers). The time between my watches was also two hours so the total time span between the start of my first watch and the end of my last was 14 hours. Another difference between my watches and those of the rest of the crew was that I had to keep watches scheduled to GMT and not to ship‘s time. Very often I wouldn‘t bother going off watch for the two hour rest period, I could just as easily read a book in the radio room instead of my cabin and listen to the radio as well.

However, if I did go off watch at the end of a 2-hour watch, I had to switch on a kind of robot receiver. This was called the Auto Alarm and it kept watch on 500 kHz – the MF Distress and calling frequency. The morse code is made up from a series of dots and dashes, a dash being three times the length of a dot. If a ship was in dire distress („going down fast“) its R/O would send out an SOS signal – a series of 3 dots (S), 3 dashes (O) and again 3 dots (S) but without a break between the letters followed by his call sign and position – he would then switch on the AKD, the Auto-Alarm‘s counterpart – the Automatic Keying Device. If his ship was „going down slower“ he would first switch on the AKD. The AKD connected to the Emergency Transmitter would key the transmitter such that it would transmit twelve consecutive dashes followed by SOS and then a long dash for direction finding purposes. Each of the 12 dashes was 4 seconds long with a 1 second interval between each dash.

The idea behind this was that any ships around that could come to the aid of the stricken ship would be keeping the same GMT watch periods and if the ship in distress decided to „go down“ within the

off watch period – no one would receive his SOS signal, unless she first „woke them up“ by using the AKD.

The Auto Alarm receiver was connected to three BIG bells – one in the radio room, one in the bridge and one in the R/Os cabin above his bunk. The Auto Alarm did not need to receive all 12 dashes to trigger the alarm bells, it only needed to receive 4 consecutive dashes of the twelve.

If the alarm was triggered and I was in my cabin at the time I would have to gallop up two decks to get to the radio room to cancel the bells and then listen out on 500 kHz for the expected distress signal/message.

The chances of radio signals from static triggering the Auto-Alarm must be pretty small you might think, after all I‘ve never heard „donner“ from lighting strikes with four consecutive 4 second bangs with 1 second intervals.

In the tropics the static level heard on a receiver is something else. As an example I was once aboard a ship approaching the Panama Canal. The night before our arrival the horizon was lit up for hours on end as a spectacular display of lighting, reminiscent of the nighttime artillery barrage that announced the start of Monty‘s (not Python) El Alamein attack. I had never heard so much static on 500 kHz – it was so severe that it completely drowned out the normal ambient radio signal „chatter“.

At the end of my last watch for the night after I had switched on the Auto-Alarm I went down to my cabin. I had barely got in when the alarm bells were triggered. Up I ran to cancel the bells and then listen for the distress signal – nothing apart from the incredible static. I reactivated the auto alarm and went back down again to my cabin. Not ten minutes later – same procedure! My cabin was in the officers accomodation deck and the alarm bell woke up watchkeepers like the 2nd Mate trying to get some sleep before their midnight watch started. After four alarms within an hour I did the only sensible thing – I switched off the Auto-Alarm.

Returning to our course from the Lombok Strait when after the few days described above we were now sailing „alone“, I experienced a weird thing that was probably caused by the earth's magnetic field and/or sunspots (which both affect radio wave propagation) but who knows for sure?

We were by this time only around 12° or 13° south of the Equator and so there was plenty of normal static which could be heard all the time on 500 kHz. When I went on watch the next morning and switched on the main receiver, I thought at first that it had given up the ghost. The scale lamps were lit as usual but on MW 500 kHz there was not the slightest crackle of static, or anything else. I then switched on the Emergency RX (short for receiver) and then the Broadcast RX - same thing. When I tuned up the Main RX through the lower HF bands - same thing, no signal, no static. This situation remained the same all day long, as if I had disconnected the receivers antennae.

I had never experienced anything like this before and it unsettled me giving me an uneasy feeling. During the day I kept walking out onto the bridge wing scanning the sea and sky looking for anything that might help me understand what was happening. I was beginning to look for UFOs as I had heard accounts of UFOs which had appeared over cars on highways causing their car radios and car ignitions to go dead, only to come alive again after the UFO had buzzed off. Maybe it was one of these „shape shifter“ UFOs that could make themselves invisible while hovering directly above us.

By this time the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Mates had all been asking me during their watch periods if I was „allright“ meaning that I looked by now like some nut who was about to jump overboard in a kind of trance. How do you explain to a „non-Sparks“ that you‘re worried because your receivers appear to be dead although they are still basically alive? That same night slowly but surely the static crackling returned but for a few days after I kept a lookout for the UFO, it might be playing mind games with me and whizz right back again!

For another few days after the „UFO“ incident we sailed along south-west bound in nice sunny calm weather. This situation unfortunately didn‘t last long as our barometer reading started to drop. It wasn‘t long before the weather around us also visibly started to deteriorate. The sky became overcast and the wind picked up which started our climb up the Beaufort Scale. The captain was visibly worried and asked me if I could get a weather report. He knew that no matter where we were at sea he always got daily weather reports but this time I had to tell him that I couldn‘t receive any for the area we were sailing in for the simple fact that there were no weather transmitting stations anywhere that covered this area. We were „off the beaten track“. We were soon rolling and pitching – Tropical Cyclone Helene was coming for us (excuse the pun) - she was very excited when we met.

For those of you who have been to sea you will know what havoc a tropical cyclone can cause. A ship‘s navigator was no doubt schooled in what causes such a weather system but a ship‘s engineer not. I when still an R/O trainee was also not given any weather related training apart from „stick your head out the porthole and see for yourself“. How to avoid seasickness? - „Don‘t go to sea!“

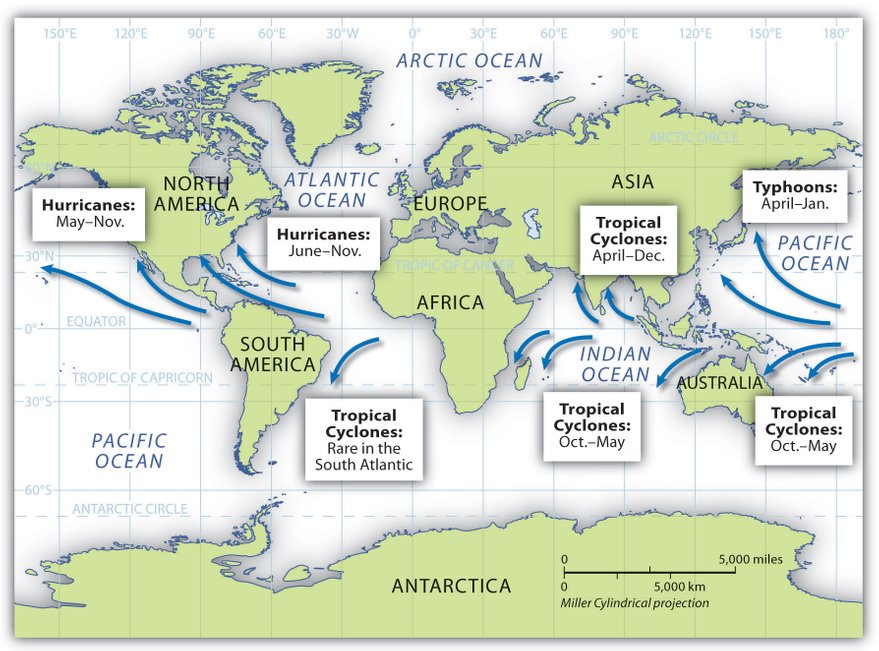

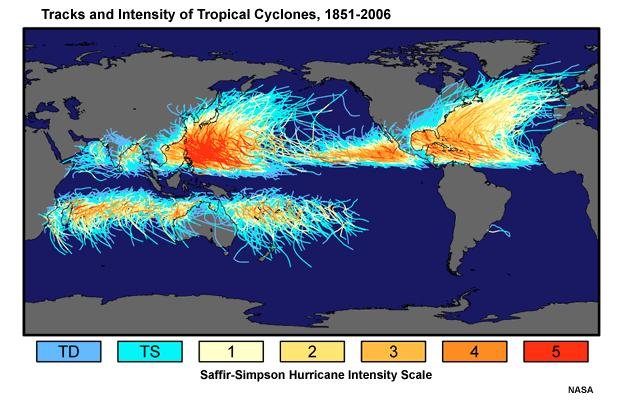

The chart above is a kind of „find the hidden treasure and win a prize“ picture like a „Spot the Ball“ competition in the newspapers of the time.

It shows a number of blue arrowed tracks that start tracking either just north or just south of the equator but NOT from the equator. Tropical Cyclones can only generate if they are at least around 500 kilometers north or south of the equator. However, most TCs are generated close to the far sides of this 1000 kilometer equator band.

Another point is that they are all generated from over the sea, not over land.

Yet another thing that can be seen from the chart is that TC s generated in the northern hemisphere above the equator start tracking north-westwards in a parabolic curve, attracted to the cooler air of the north pole while those in the southern hemisphere start tracking in a south-west curve seeking the cool air of the south pole.The direction of tracking is also due to what is called the Coriolis effect. They also never track across the equator.

And that is not all that the chart shows – the blue arrows drawn do not seem to extend much above either 30° N or 30° S. Is this just coincidence? No, there is reason behind it.

End of Chapter 14. Continued in Chapter 15.