Mandalay

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 15

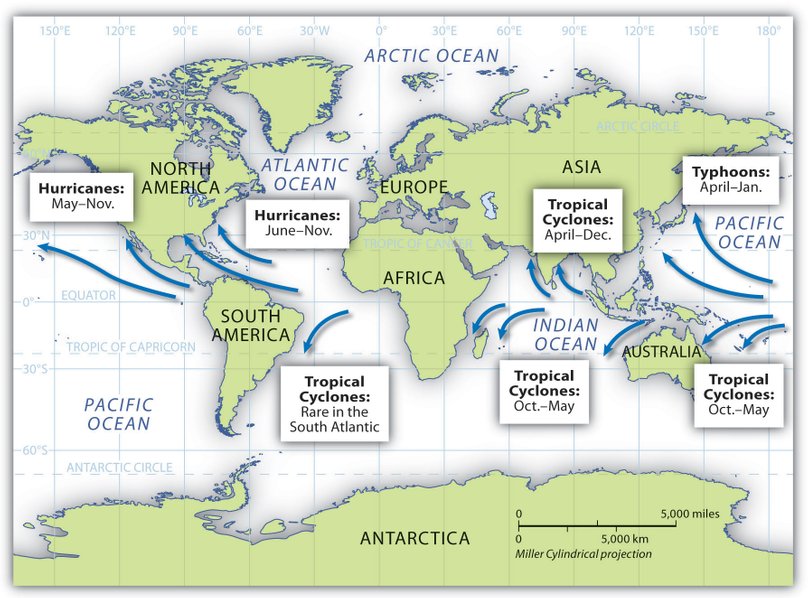

The TC tracking chart is shown once again below.

In the text boxes in the southern hemisphere in the chart above the tropical cyclones are all denoted as Tropical Cyclones no matter whether they are in the southern Pacific Ocean, southern Indian Ocean or South Atlantic.

The text boxes in the northern hemisphere are labelled either as Tropical Cyclones, Hurricanes or Typhoons but Hurricanes and Typhoons are just regional monikers. They are all the same thing – Tropical Cyclones. So, are Tropical Cyclones the same whether in the northern hemisphere or in the southern hemisphere? The answer is no, mainly due the Coriolis effect, the spinning of the Earth around its own axis.

Tropical cyclones derive their energy from the warm tropical oceans and do not form unless the sea-surface temperature is above 26.5°C. They are low pressure systems and have gale force winds (sustained winds of 63 km/h or greater and gusts in excess of 90 km/h) near the centre.

A Tropical Cyclone is born when hot moist air at the surface of the sea starts to rise rapidly – (like being in a lift in a skyscaper) and in doing so also sucks in warm air from around its base. When the warm air is shooting up the elevator, after a number of „floors“ it starts cooling down on its way as

it meets the colder air above it and this produces condensation – clouds start building up around the elevator shaft ( the „eye wall“) and these clouds can soon assume massive proportions. The whole „assembly“ (elevator shaft air and cloud formation) starts to rotate due to the Coriolis effect. In the northern hemisphere it spins anti/counterclockwise; in the southern hemisphere it spins clockwise. Providing the sea surface temperature remains warm enough it feeds the cyclone with energy causing the „beast“ to grow. The cyclone also starts rotating faster and this is what causes the gale force winds.

The gale force winds can extend hundreds of kilometres from the cyclone centre. If the sustained winds around the centre reach 118 km/h (gusts in excess 165 km/h), then the system is called a severe tropical cyclone.

The circular eye or centre of a tropical cyclone is an area characterised by light winds and often by clear skies. Eye diameters are typically 40 km but can range from under 10 km to over 100 km. The eye is surrounded by a dense ring of cloud about 16 km high known as the eye wall which marks the belt of strongest winds and heaviest rainfall.

To find out not only what the Coriolis effect is but just about anything else about cyclones/anticyclones/tropical cyclones/why the world‘s deserts are all located around either 30°N or 30°S/ and many other related topics, click on the link above. The article was written by a professor but unlike so many of his ilk he writes in „easy to understand“ English and has included many very good illustrations.

If you would rather download a PDF copy instead of reading it on-line, click on the link below:

Before returning to our meeting with Helene, two photos below show the difference in spinning direction between a northern hemisphere TC (hurricane Fran spinning anti-clockwise towards Florida) and a southern hemisphere TC (severe tropical cyclone in the southern Indian Ocean spinning clockwise).

At sea even under what could be termed as „moderate“ weather conditions, when walking around it could be a little bit like a clown‘s circus act, trying to walk in a straight line. If the ship was gently rolling, your brain could usually still manage to send you the right signals to keep you on an even keel. I once went across the English Channel on one of those giant passenger/car hydrofoil ferries when the weather was comparitively mild but when the hydrofoil stepped up the tempo it was impossible to walk like a normal human being. It was like walking across an earthquake, as if the deck you were walking on kept moving in all possible directions. It wasn‘t a violent movement, it just made you look silly like Basil in Fawlty Towers or like in a breakdance version of Irish dancing.

As Helene was rapidly closing in on us the Weybank started to roll, pitch and shudder. Anything that wasn‘t well battened down took on a life of it‘s own. The chair at my operating position in the radio room had a spindle hanging from underneath the seat which could be connected to a bolt on the deck. This spindle wasn‘t a tight rigid affair and couldn‘t clamp the chair to the deck. It just prevented you and the chair from sliding away when the ship rolled. By this time the „rocking and rolling“ of the ship had become so bad that the chair would zoom in some direction until the spindle braked the zoom but the chair would then pivot on one of its legs trying to catapult you into outer space. The answer to this was to rope your chair to anything that could stand the strain and you ended up like sitting in a spider‘s web.

By midday I couldn‘t stand it (sit it) anymore and staggered into the wheelhouse to see what was going on. The captain and all the mates were standing there hanging on for dear life. I looked at what they were looking at. Through the bridge windows I could see a wall of grey/green sea ahead that kept rising in height so much that I had to bend down to see if I could see the top of it when it rose above the top edge of the bridge windows. You could also feel the movement of the ship rising when suddenly the whole forward deck of the ship disappeared under a white boiling sea that smashed into the bridge/forward superstructure. We had just gone through the crest of the wave/wall and had started our downhill trip towards the next wall which was approaching fast.

During these mountain-climbing exercises the ship was also rolling and juddering which produced some weird metalic torture sounding acoustics. This crazy roller coasting lasted for hours on end. I do not know why but I had no fear, call it „Siebter Sinn“ (7th Sense) or whatever. I just knew that we would pull through, even when for a time things got even worse. We started to roll heavily and wedged ourselves into whatever could prevent us from being shot across the wheelhouse. When a ship starts rolling more than 20°, forget about walking anywhere.We all had our eyes glued to the inclinometer. This was a very simple but effective device that showed the roll of the vessel in degrees to port or starboard. It was in the form of a brass arrow that hung downwards from a spot exactly midship above the centre bridge window and underneath it was a brass semi-circular scale calibrated in degrees from 0° midship up to 45° port and 45° starboard. The scale wasn‘t calibrated above 45° for the simple reason that if the ship rolled more than 45°, Harland & Wolff, Belfast – the ship‘s builder obviously thought that the services of an inclinometer would no longer be required, the ship would have rolled over. A „Rolls-Royce“ inclinometer version is shown below.

You may not believe this but there came a moment when I watched the arrow moving through 35° starboard and then crept slowly up to 40°, hung there for a moment and slowly moved down again where it rapidly headed to port to do the same thing there. That was the moment when I started to wonder about my 7th Sense but luckily that was the only time that she rolled that far. At the time it happened even I was praying „please don‘t let the cargo shift“.

Every vessel has its own natural syncronous rolling period which is inversely proportional to the square root of the metacentric height and directly proportional to the beam of the ship. If the vessel encounters a series of waves in such a manner that the wave period matches the rolling, the vessel will have no time righting itself before the next wave strikes.

Another thing about rolling is when your own centre of gravity starts going somewhere else. For a brief moment you get the feeling of weightlessness, like the astronauts in training who were jetted up to the stratosphere, the aircraft then abruptly headed downwards again but at the point of transition from up to down they would experience zero gravity for a short time. Years later I was aboard a big container ship doing sea trials in the North Sea when we also started to roll heavily. There were a lot of sub-contractors aboard either there to get their equipment tested or as in my case to fix the radars if they decided to breakdown. I was in the bridge ( which was not just big but wide) when we took a bad roll to starboard and I watched in horror as one of the contractors standing at the port side lost his grip and flew like Superman right across the width of the bridge and smashed into the starboard bulkhead. He only survived because he didn‘t fly head first but he broke a lot of ribs and other bones. We had to interrupt the sea trials and sail back to where we could get him ashore to a hospital – this was in the days just before helicopter evacuations or pilots boarding via chopper became almost commonplace.

Returning to Helene she slowly lost interest in us as by nightfall we were climbing hills instead of mountains and although still rolling like a pig, nowhere near as bad as what we had already gone through. Slowly we escaped but high winds, rough seas and torrential rain dogged us for days after.

For those of you reading this but have not gone to sea, below is an animation to give you an idea of how it was for us in the tropical cyclone.

I was long since well and truly in love with Weybank. It would have been perfect if she had been christened with a name like Sally or Mojiko but being a Bank Line ship I‘m sure she wasn‘t christened at all – just shoved down the slipway unceremoniously in Bank Line Owner fashion – like a whore being pushed out by her pimp – „get on with it and start earning your keep, you bitch!“

No champaigne, not even a bottle of Guiness bid her a „safe and happy …..and all who sail on her“.

Month after month she had carried us safely and uncomplaining through everything that nature could throw at her. Not once did we have to heave to in the middle of nowhere to change a piston, unlike aboard a number of other ships that I sailed on. You trust her with your life in the true sense of the word in the knowledge that she won‘t let you down. You even start talking to her like during the cyclone - „come on girl, you can do this easy“. I‘ve seen a lot of car owners who feel the same with their cars – are we all nuts? (yes).

After roughly 19 days at sea since leaving Davao, we arrived at dusk at a remote bunker terminal in Capetown‘s „boondocks“ and sailed at dawn the next day – a quick overnight „Formula 1“ pitstop – we didn‘t have to change the tyres – just fill her up. Our next waypoint is the Cape Verde Islands – 3369 sm distant, 9-10 days sailing time.

On leaving Capetown we entered into the Benguela Current, a cold water current which is 250-300 km in width and flows slowly, about 1 kt speed in a northerly direction along the south-west coast of South Africa and Namibia.

The so called Skeleton Coast is a 40 km wide and 500 km long coastal stretch in Namibia, a hostile but fascinating area. It is the northern part of the Atlantic coast of Namibia and south of Angola from the Kunene River south to the Swakop River. It is associated with shipwrecks, and stories of sailors walking through the desert in search of food and water. The name is derived from the bones that lined the beaches as a result of whaling operations and seal hunts. A few of the skeletons were human. In the days of „windjammers“, being shipwrecked on its coast would turn into a nightmare for any survivors of the actual wreck, as the photo below will attest to. Note the broad surf and the massive sand dunes rising directly from the water line.

When sailing off the coast of Namibia we experienced the Cassimbo which is the name given to fog in this area caused by the meeting of the cold ocean current and the warm winds from the desert and

is responsible for the many shipwrecks that are littered up and down the Skeleton Coast. It can also extend to the width of the Benguela current.

As to our course towards the Cape Verde waypoint and beyond to the Bay of Biscay I can remember nothing untoward occuring. We all fell into our watch keeping routines and the days passed by uneventfully – no storms or accidents aboard or breakdowns – with each sea mile left behind us, slowly getting closer to home we weren‘t even bored as we might otherwise have been.

In the interim I‘ll describe an incident which occured when we were in Yokohama which I had totally forgotten. Describing Yokohama in a previous chapter I had stated that as we stayed for only a day I couldn‘t write much about it. Well, I could, if only I had remembered…..

According to international law each ship which had a radio station installed, no matter its nationality, had to have a Ship Licence (pertaining to the radio station) issued by the government of

the nation under which flag the ship sailed. In our case the license was issued by Her Majesty‘s Postmaster-General and a copy of it had to be displayed in the radio room. The License stipulated

what frequencies and types of emissions the radio station was authorised to use and the same for the Lifeboat Station and for the Radar Station. It also contained five closely typed pages containing rules to be followed etc., etc.

To make a long story short, each Radio Station had to undergo a yearly radio survey and inspection

to ascertain that the radio equipment was functioning A1OK and that the rules etc. were being adhered to. For this reason if a ship was in British waters when its yearly survey was due, a British Post Office Telecommunications official would board the ship to carry it out. Who would do the inspection if the ship was not in home waters? An authorised government inspector of the country which the ship was visiting when its inspection was due. On inspection by such an official if any equipment defects were found, the inspection would be abruptly terminated. The faulty equipment would have to be repaired and thereafter a new inspection date arranged. The ship would not be allowed to sail until the so-called Radio Safety Certificate was issued by the inspectors i.e. the terms of the inspection had been met.

When we were still in Osaka the captain told me that the yearly inspection would take place in Yokohama. I told him not to worry, all of the radio equipment was in top condition. As soon as we arrived in Yokohama our Japanese ship‘s agent came aboard and told me how the scene would be set. First an employee of a Japanese marine radio company (not a government official) would come aboard to do the survey. If everything was found to be A1OK then he would telephone the government inspector who would then arrive for the official inspection. The agent then told me that after a successful inspection and it came time for the inspector to sign the certificate it was the norm that he expected to be offered a good few drams of premium Scotch i.e. whisky and not offered from a half empty bottle either!

As we were in port the bond locker was sealed so I ran around all the officers accomodation asking if anyone had an unopened bottle of Scotch – alas the answer was no so I went to the captain and asked for some Yen so that I could buy a bottle ashore. Off I shot ashore and at the front door of any promising looking store I mimicked taking a glass to my lips while pointing at the store‘s shelves and shouting „Whisky?“. It didn‘t take long when one kindly gentleman pointed at a shop down the street and said „Whisky!“. „Arrigato!“ and off I ran. When I ran into the shop I asked „Whisky?“ whereupon the proprietar bowed and then gestured for me to follow him, up to a shelf loaded with Japanese Suntory whisky – not a bottle of Scottish Scotch in sight. Time was of the essence so I ended up buying a one litre bottle of the most expensive of the Suntory range. It came inside a very nice looking box as well. Off I galloped back to the ship and as soon as I got aboard I took it to my cabin and placed it under my writing desk on the right hand side. I then locked my cabin door and shot up to the radio room. I just made it before the Japanese surveyor arrived to do the pre-inspection check.

The surveyor was a young, tall Japanese who appeared to be just a couple of years older than I. There was none of the usual bowing or attempts at small talk - he started off more or less ordering me to do this or that in an arrogant way. „Switch on the main transmitter!“ - that kind of thing. I played along for a bit – until he told me to switch on the emergency transmitter – as soon as I did he pressed the morse key down and started twiddling the main tuning knob. Doing something like this would destroy its main transmitting valve so I immediatly knocked his hand off the key and then gave him a piece of my mind. I told him that before he arrived all of the equipment was functioning perfectly and I was going to keep it that way.

Anything he wanted to survey, I would do the operating and he could do the watching. If he didn‘t like it, he knew where the gangway was! This must have got him thinking overtime especially of having to explain to his superiors why he was ordered to leave the ship. It is a paradox because in the Ship License it stipulates that the radio officer will not permit any other person than himself to operate the equipment. To give him some credit his attitude then immediately changed for the better and we concluded the survey. He then buzzed off to telephone the inspector „ready when you are !“

A half hour later not one but two inspectors arrived. Both of them very polite elderly gentlemen in grey suits. They both stood in the background ticking off items on their clipboards as I operated the equipment – with my Japanese survey „friend“ giving a running commentary in Japanese.

All went well and my „friend“ then said that the inspection was successful and could they sit somewhere to fill out the paper work ( a hint about a few Whisky drams). I told them that we could do it in my cabin while having a few whiskys to which their eyes lit up. Down we traipsed to my cabin. I unlocked the door and ushered them in, asking them to take a seat. Up to this point I had not mentioned that it was Japanese and not Scottish whisky which they were about to receive and I was a bit apprehensive as to how they would take it when I spilled the beans. However, I never got to that point because when I threw a glance underneath my writing table – the whisky was gone!

It didn‘t need Sherlock Holmes to deduce who had removed it. It could only have been taken by my

steward who happened also to be the „Captain‘s Boy“ (captain‘s steward). He was the steward for only the two of us. My cabin door had a Yale key type lock, not an easy lock to pick even if you were an expert. My steward however had a pass key. At sea we never locked our cabin doors, only when in port. I said „excuse me“ to my guests and had a quick look around my cabin, checking in my wardrobe, under the day-bed (couch), the drawers underneath my bunk – nothing! I then opened my cabin door and shouted down the alleyway towards the dining salon - „get the captain‘s boy up here immediately!“. After an embarrassing five minute wait in which the Japanese held a muted conversation amongst themselves , in slouched the captain‘s boy.

I had been fortunate during most of our voyage to have had good stewards – of the cheerful and efficient kind with whom one could hold normal conversations with about family life, aspirations etc., etc,. Unfortunately, each time we returned to our proxi „home port“ Calcutta, most if not all of the Indian crew were changed. With the last of our crew changes in Calcutta I ended up with our present „Captain‘s Boy“. This steward was slightly taller than me, carried a lot of overweight and slouched around in sandals while wearing a white kind of Kaftan and white trousers. Talk about slow motion! He was lazy, performing his „duties“ with a minimum of effort – I would sometimes watch him as he for instance gave the washhand basin a perfunctory wipe with an old cleaning rag

instead of running the water and giving it a bit of a scrub – that kind of thing. Sweep the floor and carpet, empty the gash can (litter basket), fill up the water caraffe, make the bed (bunk) and change the bed sheets once a week – that was all that his work entailed as far as I was concerned. He had a sly look about him and projected a kind of latent insolence. He was very light skinned and it appeared to me that he seemed to think that this gave him a kind of superiority over his fellow Indian compatriots aboard. I instinctively took a dislike to him and I am sure the feeling was mutual.

When he arrived at my cabin door I asked him what he had done with the whisky. „I threw it away, it was standing next to the gash can“. I replied that it was nowhere near the gash can, the gash can was behind the other side of the writing table. I also told him that no one in his right mind would throw such a thing away without having a good look inside it at first – in its nice illustrated box – the weight of it alone would induce a good peek inside. I told him to go and retrieve it from the rubbish (when in port the ship‘s rubbish (meal leftovers, empty bottles etc.) couldn‘t be just tipped over the side polluting the harbour. In ports, rubbish was tipped into empty oil drums which were lashed to the stern railings of the ship. Once the ship had left port and was out in the open sea, the contents of the oil drums would be tipped into the ocean). The captain‘s boy replied that he couldn‘t retrieve it as he had thrown it over the ship‘s side into the harbour instead. I accused him of being a blatant liar and to get out of my sight. My Japanese guests who had no doubt got the gist of this new kind of Kabbuki show offered their commiserations „Vely solly...“. To my relief they signed the „Safety Certificate“ without further ado and I then accompanied them to the gangway where we exchanged polite farewell greetings. I had just returned to my cabin when through the open door I saw a chain of stewards, led by the Chief Steward, passing by and then up the staircase to the captain‘s cabin. In the alleyway I heard snippets of „Marconi Sahib say...“, „bad words..“.

Shortly thereafter I saw them passing by my cabin door doing the „Congo“ in the opposite direction, minus the Chief Steward. Not long after that the captain appeared at my cabin and asked me what had happened. I told him what had happened to which he replied that he commiserated with me but that „we now have a problem, the stewards have all gone on strike and will remain on strike until you apologize in front of all the other stewards to the steward in question“. The Chief Steward had told the captain that the Captain‘s Boy had stirred up all the other stewards into supporting his demand for retribution. This was indeed a problem and it would start with our lunch which we would not receive. In the days of yore a „strike“ would have been another word for mutiny, punishable by being tied to the main mast and getting a dose of the cat, being hung from the yard arm or keel-hauled. Alas, those days were long gone. The captain had always been a good skipper and it wasn‘t right that he should end up with the problem. I myself could see no other solution (apart from beating the crap out of the CB) and so, swallowing my pride, I told the captain that I would apologize but on one condition – that the CB would cease being my steward for the rest of our trip, even if it meant me cleaning my own cabin etc. I added that the CB, due to the „bad blood“ now between us making any further daily contact „impracticable“ to say the least, would agree to this (I didn‘t mention that he would also be happy to have even less work to do, having now only to serve the captain).

The moment came when The Chief Steward, CB, all the other stewards, the Captain, First Mate and the Bosun all gathered in the dining salon to hear my mia culpa confession: „I apologize profusely for offending steward xxxxxxx on the xx/xx/1969, wrongly accusing him of dishonesty in regards to an item missing from my cabin. I sincerely regret the accusation made and hereby ask the accused for his forgiveness in the matter“. A short pow-wow followed between the chief steward and the CB whereupon the chief steward then stated: „The Captain‘s Boy accepts your apology but only on the condition that he will no longer serve as your cabin boy“. „Agreed“ - end of the Mutiny on the Weybank. The CB still had a pass key so from that moment on I took all my personal papers (letters and photos from Inge etc.) up to the radio room and locked them up there – CB didn‘t have a pass key to get in there and had no business being there in the first place if caught. Even when he was my cabin steward, he was not the one who brought my morning and afternoon coffee up to the radio room – neither was he the one who swept the radio room every day.

Suntory retrospective; a US Marine wrote the following about the bloody battle on Tarawa atoll during WWII:

Just behind the coconut-log wall where the men of D Company had died there is a pit containing a 77-mm. gun, whose ammunition supply had been half exhausted. A few yards further along the wall there is a 13-mm. machine gun. Inside the gun pit is a half-pint bottle of the only brand of whisky I have ever seen in Japanese possession. The label, like the labels of many Japanese commercial products, is in English:

Rare Old Island Whisky

SUNTORY

First Born in Nippon

Choicest Products

Kotobukiya Ltd.

Bottled at our own Yamazaki Distiller

As I have written before, being at sea over long periods has something in common with being a prisoner in Alcatraz – both surrounded by water. This may sound a bit over the top but the similarities between a convict serving time and a seaman at sea are striking. The life of a convict is regimented by a combination of the prison warders and the clock. The convict will probably spend most of his time in his cell but otherwise his cell door is opened in the morning – he gets to do his ablution followed by breakfast then either work (if permitted to) at some sweatshop making car number plates or sewing mail sacks, has a lunch break and then back to the sweatshop. He might get an hour‘s recreation time mingling with other prisoners in the prison yard and by then it‘s time for the evening meal. Nowadays they might even be permitted to watch TV for a couple of hours in a common room but then comes „lock up“ - back to their cells until the next morning when the cycle is repeated. As we all know, prisons are violent places and who really runs them, the warders or the convicts is sometimes questionable. Apart from this, even the most placid of prisoners can at times go stir-crazy, errupting violently. A prisoner might be able to peep over the wall or through the fence at that which he cannot attain. He can‘t walk out through the gates to go to a movie, a dance, for a Big Mac, hook up with a girlfriend, visit his parents or siblings, go on a vacation, join a sports club, wander through shopping malls – the list of what he can‘t do is just about endless.

When at sea, we can‘t do any of these things either. Instead of a cell I had my cabin. We also led a regimented life, the only difference being that we had to control ourselves with self-discipline. Admittedly a deckhand for instance had to follow the orders of a Mate or Bosun but these were work related. Instead of going to a sweatshop, we had to keep our watches. Breakfast, lunch and dinner broke the monotony. We didn‘t have TV or movies to watch, no internet to Skype or phones to contact loved ones. Our main recreation time was spent reading. A lot of possible hobbies had to be given the miss because we had no room to carry them out in or if we did we could not get our hands on re-supply of items required to maintain them. We had alcohol aboard but at sea most of us would be very careful not to get inebriated. I might at the most just drink one can of beer at the end of my last watch of the day. And so, like an old-age pensioner, each day seemed to merge with the last - „what day is it?“, only the weather around us changed. However, redemption for us was always the next port of call – instead of „Spring Break“ we had „Prison Break“ (not to be confused with prison breakout Hi Hi).

When the academic Erol Kahveci surveyed British prison literature while researching conditions at sea, he found that “the provision of leisure, recreation, religious service and communication facilities are better in U.K. prisons than… on many ships our respondents worked aboard.”

Instead of this general situation improving for seafarers over time in the future, it got a lot worse, especially for those serving aboard container ships:

In 1965 the Bank Line fleet had 57 ships, all of them around 12000 dwt. By 1978 the Bank Line fleet had drasticly shrunk to only 18 ships! What had caused this rapid demise?

The Bank Line fleet was comprised of what is termed „multipurpose“ ships, a better word for „general cargo“.

General cargo meant just that – you name it, if Bank Line could get it to fit aboard, in it went. All kinds of cargo would be lowered into the holds and stowed next to or on top of each other (with the exception of certain hazardous cargoes that had to be seperated). General cargo (also called Breakbulk) are goods that must be loaded individually and not in containers nor in bulk as with oil or grain. Breakbulk cargo is transported in bags, boxes, crates, drums, or barrels. Bales of jute, boxes of tea, timber, electronic goods, automobiles or automobile parts, crates filled with shoes or cutlery or heaven knows what. At other times all of the holds were just filled with copra (a Bank Line favourite cargo), wheat or some other bulk cargo. Bank Line (BL) ships would go anywhere to pick up cargo and for this reason they limited the size and hence the draft of their vessels so that they could navigate up rivers like the Hooghly to get to it. Often a BL ship would moor to a river bank in the middle of nowhere while loading/discharging cargo with her derricks from/to the likes of Oxcarts.

Discharging and then loading general cargo at ports like Calcutta could take weeks before the ship was ready to sail again. These long stays in port were caused by the time consuming process of lowering cargo nets into the holds, filling them up and then hauling them out. In the holds and tween-decks cargo had to be rearranged and stowed securely to prevent them shifting in bad weather at sea. Cargo plans had to be redrawn so that the individual cargoes could not only be later located but also to maintain the stability of the ship.

When ships carried general cargo, a cornucopia of everything, in bales and barrels and piles – and dockers unloaded all by hand, there was more time ashore. There was rest and recuperation. On a voyage in 1954 a typical cargo ship, the SS Warrior, carried 74,903 cases, 71,726 cartons, 24,036 bags, 10,671 boxes, 2,880 bundles, 2,877 packages, 2,634 pieces, 1,538 drums, 888 cans, 815 barrels, 53 wheeled vehicles, 21 crates, 10 transporters, 5 reels and 1,525 undetermined items. A total of 194,582 pieces, all of which had to be loaded and unloaded by hand. The total weight came to just under five thousand tons of cargo and would have taken weeks to move.

In 1955 a US American trucker named McLean who ran his own trucking business came up with the bright idea of a container which he promptly designed and produced – a container with standard dimensions.

McLean built his company, McLean Trucking into one of United States' biggest freighter fleets. In 1955, he purchased the small Pan Atlantic Steamship Company from Waterman Steamship and adapted its ships to carry cargo in large uniform metal containers. On April 26, 1956, the first of these rebuilt container vessels, Ideal X, left the port of Newark in New Jersey and a new revolution in modern shipping resulted. This trucker revolutionized not only the trucking business, he unknowingly at the time sounded the death knell to not only the Bank Line but also to the British and US Merchant Navies.

After the Second World War, the great powers in shipping were Britain and the United States. They had ships and supplied men to sail them. In 1961 the United Kingdom had 142,462 working seafarers. The United States owned 1,268 ships. Now British seafarers number around 24,000. There are fewer than one hundred ocean going U.S.-flagged ships. Only 1 percent of trade at U.S. ports travels on an American-flagged ship, and the U.S. fleet has declined by 82 percent since 1951.

By 1965 Japanese and Korean shipping companies had had a good think about the use of containers and had invested in building ships centered around the dimensions of standard containers, a la McLean.

Instead of loading general cargo with cargo nets, all they had to do was load the holds up with containers which all had the same size and which would fit neatly into the dimensions of the ship‘s holds – which were designed for just this purpose. This concept rapidly found acceptance by freight companies worldwide and who adapted their own resources to meet those of these new container ship companies. By the early 1970‘s many of these container ships had already become the largest ships in the world but with an inherent increase in draft. To accomodate such large vessels, many ports worldwide built new deep-water facilities which were often by necessity remote from the location of the original port. Thus, new rail and road links were also built to be able to transport the containers to and from the vessels. These new container ports also built massive crane gantries to enable rapid loading/unloading of the containers. Due to this, most container ships adapted by ridding their main decks of their own cranes/derricks but keeping usually a single mobile gantry of their own, „just in case“. This in turn opened up more space for stacking up containers on the main deck.

In the 1960s the Bank Line had derisively refused to believe that the container ship concept held any future and instead steadfastly stuck by their multipurpose general-cargo guns. The Bank Line was not alone by any means in this belief – many other British and foreign shipping companies would soon pay the ultimate price. By 1975, just 10 years on, they were having difficulty in obtaining cargo to transport. This was a time when you could see many a general cargo ship which had undergone some quick shipyard doctoring in an attempt to make it into what it just couldn‘t become – a container ship. To gain the finance to be able to get their foot into the container ship market door, the BL started rapidly trying to sell off their general cargo ships. To avoid any new-ship building delay they started instead to buy second-hand container ships but it was all too little, too late.

Now, in 2020 some of the world’s biggest container ships are over 1,300 feet long with a width of 180 feet. Their engines weigh around 2,300 tons, their propellers 130 tons, and there are twenty-one storeys between their bridge and their engine room. They can be operated by crews as low as just thirteen men (and women) with the aid of sophisticated computer systems and carry an astonishing 11,000 20-foot containers. If that number of containers were loaded onto a train it would need to be 44 miles or 71 kilometers long!

The silhouette image above shows the size of the Weybank in comparison to a container ship behemoth. The container ship is three times the length of the Weybank!

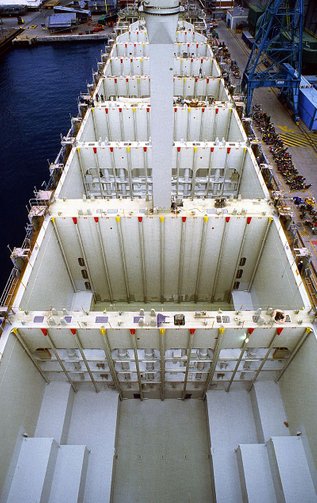

Below, a view of a container ship‘s holds :

Returning to the point about the conditions aboard the Weybank, you might assume that since technology had advanced in leaps and bounds enabling such container ships to be built and operated in the first place, the conditions for the manpower crewing them would also have improved in step.

Unfortunately this is not the case. The shipping business is a cut-throat one. The ship owners are constantly in a tight-rope balancing act. On the one hand the international freight rates – how much a shipping company can charge for transporting containers from A to B, i.e., profit. On the other hand the running costs (losses) of keeping the ship in operation, mainly in the tons of fuel the vessel guzzles up everyday at sea to keep her moving but also in maintenance costs to keep her ship-shape, port charges, Panama Canal transit charges, pilot charges and, and, and…. Last but not least – crew wages!

Into the sixties most merchant navy ships sailed under the flag of their owners nationality. Ships of the Bank Line for instance sailed under the „Red Duster“ , the British Merchant Navy ensign. British registered ships had to comply to the national rules governing the running of said vessels - crew wage scales, union agreements, safety regulations etc.,etc., In other words the shipping owners' hands were tied by these rules. The same situation applied to other merchant navies, those of the US, Dutch, German or Norwegian for instance. Keeping to the rules cost ship owners money that they were loath to spend but it didn‘t take long for them to concoct a way out: „Flags of Convenience“ - very convenient for the ship owners. This entailed the simple act of an owner getting his ships struck from his own national registry and instead re-registering them under the flag of a foreign nation, preferably a poor nation and even better, one that didn‘t even know what a ship looked like (Mongolia – a land-locked country for instance, no joke!). Suddenly ships were popping up everywhere with either Monrovia, Panama City or Liberia painted on their sterns as their home registration. What benefit did a ship owner gain from „flagging out“? Liberia for instance is a small West African country that had a history of strife and poverty. All the shipping company had to do was to pay a registration fee and „Bob‘s your uncle“. For the Liberians it must have seemed like taking candy from a baby – money for almost nothing. The crux of the matter was that a ship under the Liberian flag was now also under the juristriction of Liberia. The only thing Liberia was interested in was in the registration fees – did they even have any national rules pertaining to ships sailing under their flag? „Tank you for da money, now go away“ (it didn‘t take long for them to demand a little tax as well once they learnt some of the ropes).

The ship owner still kept his head office in place, had never been to Liberia and probably couldn‘t even point it out on an atlas but now he could do what he liked with his ship. The benefits of flagging out vary according to registry, but there will always be lower taxes, more lenient labor laws, no requirement to pay expensive American or British crews who are protected by unions and legislation. The flag of convenience, under which ships can fly the flag of a state that has nothing to do with its owner, cargo, crew, or route. Another thing was money spent on the upkeep of the vessels – the less the better which was why one started seeing more and more of these vessels covered in rust instead of paint. Safety regulations went overboard – lifeboat davits seized with rust, fire extinguishers were not replenished, neither were navigation charts nor were they updated, on and on the list could go..

As to the present day container ships, nearly all of them sail under a „Flag of Convenience“ but their owners cannot afford to ignore their upkeep. The intricate technology comprising the vessel punishes any neglect and more than ever „time is money“- a breakdown at sea (or even in port) is a nightmare for a ship owner. We don‘t even know who owns the majority of the container ship companies, they are shrouded in (convenient) secrecy.

Aboard the Weybank we had a crew of almost 60 seafarers, for the relatively small size of our ship an unbelievable number. For the course of this narritive I will split the numbers. From the total manpower aboard, 16 were officers and the rest were Indian crew members. The officers were all British – three of them had dual British/Indian nationality. When I now refer to the crew, I mean only the Indian deck and engineroom hands. How could the Bank Line afford to employ such a large number of crew? Simply because the Bank Line had made contracts with the Indian government for the recruitment of cheap labour. These crew members came under completely different terms of agreement than those of British crews, the major difference being in the wages which they were paid which were at the most about a third paid to a British. Exactly how much less I was unable to discover. Companies like the Bank Line that similarly employed such Indian or Chinese crew were always quick in pointing out that they were doing these crew members a favour – that they were earning a lot more than they could ever make from a job ashore, providing they could even find one in the first place. What such companies omited to mention was that they were very happy being able to crew their ships with non-British crew. Apart from the higher wages they would have to pay them, British crew members were usually union card holders. They also generally had a culture-based disrespect of authority – in other words they could be and often were difficult to handle by the officers.

Later, aboard my first German ships, the crews were mainly Spanish (maybe because we ran a liner service to South America) but not much later Philippinos slowly came to the fore as crew members.

These ships sailed under the German flag i.e. had not flagged-out so why were they employing foreign crews? Simply because they could not get enough Germans to man their ships. About the only ones they could get at that time were those that by signing on avoided national service with the Bundeswehr, the German armed forces. It was either that or moving to Berlin to work – another loophole. Things became so bad for the German shipowners that they opened up training schools in the Pacific around New Guinea – where the derogatory term „Kanaka“ was coined (the name given to such aspirants) in the hope that the graduates would be able to fill the gap.

I wrote in a previous chapter about Philippino women working abroad to be able to support their families. Now, in 2020 most of the world‘s merchant fleets are to a great extent manned by Philippino crew members.

The rush to seafaring began in the Philippines in 1974, with encouragement from, at that time President of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos. By now there are ninety maritime academies pushing out forty thousand seafarers a year. They send home more than US$ 5 Billion a year in remittances. Flagged-out shipping companies get these crews from Philippino pools – manning agencies of dubious character. Some manning angencies require job seekers to work for months unpaid before deigning to give them a one-of contract. If they manage to get such a contract, unlike the senior officers they don‘t belong to the ship but to the contract.

Many a contract holder tries to stay with the ship as long as he can to push back the day when he will eventually have to start all over again – trying to get another contract. Some manage to stay for as long as a year aboard but shipping companies know that after around 6 months at sea a crew member can become a risk – in the „stir-crazy“ sense and will get rid of him, according to the motto „plenty more where he came from“.

What is an average wage? It depends on whichever Manilan exploiter they had contracted under and it is in the interest of such contractors to keep such information under wraps. The sum of around US $ 1,000 per month is not just a guess on my part. Apart from having no social or health security benefits only roughly 10% of them had any access at all to the internet to Skype or send emails. In some cases to send an email they had to hand it in to the captain who would then send it on from his Inmarsat terminal. There were usually a few computer PCs aboard available for them to play PC games on but without internet access. Most of these container shipping companies also have a no-alcohol policy. There was usually a room aboard fitted with a stationary bike trainer or the like but which were seldom used. The officers mess room tables were covered with table cloths and the associated porcelan and silver. The crew mess room just had mica table tops. Container ships have fast turn-around times in port, often in and out again in less than 24 hours. The container terminals are usually in remote areas far from adjoining cities. To be able to visit a shopping mall would entail expensive taxi fares which they could ill afford. There are now more than 10 million Philippinos who work abroad in this kind of diaspora. Many of the wives of Philippino seamen also work abroad while their children stay with grandmothers. Such husband/wife teams try to stick at it for up to 10 years or even more in the hope that they will be able one day to afford a decent house of their own or open up a small business later to keep them and their (often extended) family alive.

Many also stick at it to pay for the education of their children in the hope that they will one day have a better life than they themselves have.

The Philippino seaman at sea quickly learns to keep his mouth shut and any grieviences he has to himself. Any persistant complaints he has could get him into deep water: being fired from his job and having to return to the Philippines at his own expense, only once there having to pay the contractor for breach of contract and possibly being then blacklisted from ever again getting another contract.

In practice, the ocean is the world’s wildest place, because of both its fearsome natural danger and how easy it is out there to slip from the boundaries of law and civilization that seem so firm ashore. If something goes wrong in international waters, there is no police force or union official to assist. Imagine you have a problem while on a ship. Who do you complain to, when you are employed by a Manila manning agency on a ship owned by an American, flagged by Panama, managed by a Cypriot, in international waters?

In 2010, a female deck cadet—an apprentice navigator—was aboard a good ship, the Safmarine Kariba, run by a good company. Six months later, a shipmate of hers reported to the captain that she had been raped by the Ukrainian first officer. He summoned the cadet and the first officer to his cabin the next day, as if an alleged rape is a regular human resources matter. The cadet didn‘t turn up because she was by then already floating dead in the sea off the coast of Croatia. Instead of an investigation by the country under which the ship was registered it was unanimously decided by all that the cadet had (conveniently, again this word) commited suicide by just „jumping over the wall“. This is sadly not the only such incident – there have been cases where crew members have been overpowered and thrown overboard.

The shipping industry is a prime example of what an unfettered free market does to a workforce, of globalisation at its reddest in tooth and claw. Flying flags of convenience, British shipping has been allowed to register in low-pay, low-regulation countries. That exodus really took off in the wicked 1980s when the number of British merchant navy officers was cut by two-thirds, replaced by cheaper foreign staff. Now only a third of British-owned shipping is registered under a British flag.

Can Britain rule its own waves again after Brexit, restoring its ships to the UK flag with decent pay and safety conditions? No chance, since Britain has been the strongest lobby in Europe against reform. Of EU nations, Britain protects its own sailors least from unfair, undercutting competition, and issuing most “certificates of equivalent competency” to foreign mariners so they can work on its ships.

Once Britain is outside the EU, don’t expect welfare, wages and working conditions to be high among their priorities as they attempt to strike new trade deals. Indeed, the risk is that after Brexit shipping companies based in the UK will try to drop existing EU regulations. Others may leave because they need an EU base: Stena Line warned immediately after the referendum that it might re-flag its UK vessels.

A manning directive to ensure that ships sailing between EU states are paid and regulated under EU law has failed to gain approval in Brussels for years, defeated by ship owners wanting to hire cheaper non-EU crews.

Compare this with how the US protects its industry: all ships working between US ports must be US-built and crewed. Many countries do likewise. But in Britain and the EU it’s a global free-for-all, where the cheapest contract wins. The result is a collapse in the British-registered shipping industry, now only 0.8% of the total worldwide. Why would owners pay British wages when they can hire crews elsewhere for much less?

If one company does it and undercuts the rest, then all must follow suit in bidding for contracts. Only government intervention can prevent a race to the bottom.

Meanwhile the government turns a blind eye.

To be continued…..