Mandalay

Kai Tak served Hong Kong for over fifty years before finally being closed down and as far as I know there were only three serious incidents throughout all those years. One involved a US Marines Hercules on take-off, another a China Airlines flight which skidded off the end of the wet runway into the bay after a typhoon (as its tailfin was sticking up preventing flights from take off, it was detonated off with an explosive charge before the aircraft itself was later lifted and removed from the bay). I can‘t remember what the third incident was.

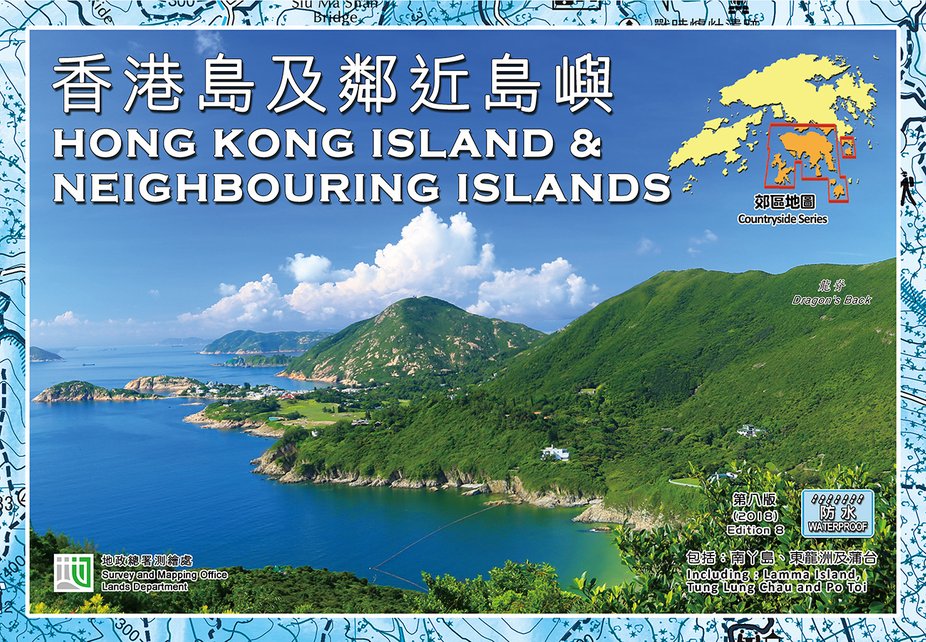

My final day was spent taking the tram as far as it went eastwards and then taking a taxi to get as close to „Dragon‘s Back“ as I could. As I said before, around 70% of Hong Kong Island is uninhabited and the views around the mountains are stunning. Well trodden trails lead you over the ridge backs. Also in the New Territories there are areas with stunning scenery. Below a HK trail map cover from the HK Survey and Mapping Office of the „Dragon‘s Back“ area.

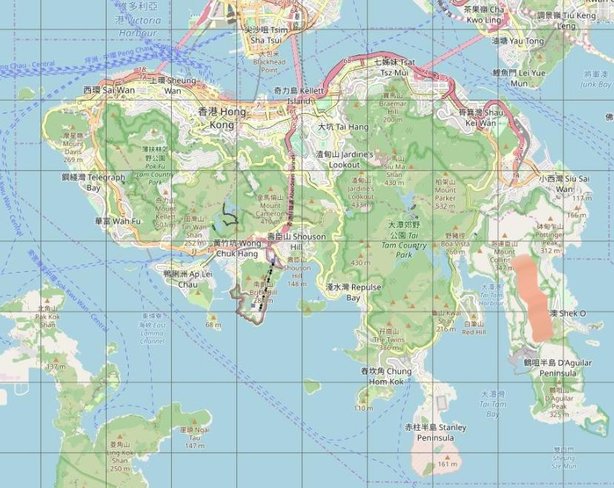

The „Dragon‘s Back“ area is marked on the map above.

This is the Hong Kong that I experienced. A lot written about little to do with the ship I arrived on but ports like Hong Kong were the compensation for many a boring day which we spent at sea literally being a captive of our ship until we reached port.

In Hong Kong‘s Victoria harbour you would always see at least one or two (or even more) Blue Funnel or Ben Line ships moored. These were cargo liners that ran a regular route from the UK, through the Medi and Suez Canal across to Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong and Japan.

Because they were regular visitors, it didn‘t take long for the crews of these vessels to choose their favourite bars as their „home away from home“ including no doubt many a „wife away from home“ into the bargain. They had the time to „suss out“ the island. We aboard our „tramp“ had no such opportunity – we were „here today, gone tomorrow“, most likely never to return after leaving, at least not with the same ship. We would be sometimes a bit envious of these BF and BL crews but on the other hand if we had „been on the same boat“ I would probably have not got further ashore than the first of the „home“ bars and into the arms of some „Suzy Wong“ (still however not such a bad prospect).

Before leaving, a farewell song from a beautiful Chinese singer from Hong Kong with glittering eyes who became almost famous overnight after briefly appearing in the movie „Year Of The Dragon“ (starring Mickey Rourke in 1985) as a background sub and sang „Tian Mi Mi“ during the credits at the end of the movie. I wrote „almost famous“ because nobody knew who she was, her name did not appear in the credits. I only found out her name much later – Myra Chen – and then only because when in Taiwan twenty years later, I met her „twin“ who to this day has a deep place in my heart. Life is full of unexplainable „coincidences“. Our next port of call after HK was Kaohsiung in Taiwan – where the „twin“ was born but at the time I arrived aboard the Weybank she was only 11 years old – her surname was also „Chen“.

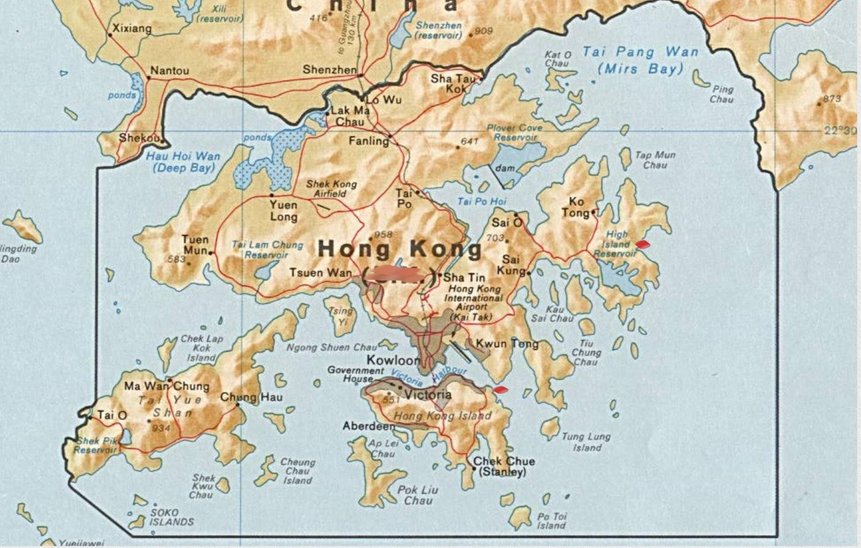

We departed HK next day through the Lye-Mun channel (marked on the map below) bound for Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

I never bothered with the usual tourist attractions in HK, the funicular rail up to Victoria Peak or the floating restaurants at Aberdeen Harbour but I didn‘t miss them one bit as the „farewell“ photo below of the beaches of Tai-Wan and Ham-Tin-Wan, viewed from Sharp‘s Peak in the New Territories will attest to (this area is also marked in the map below next to „High Island Reservoir“). Adieu HK and all her citizens and may the Dragon protect you from the PRC!

M.V. Weybank - Chapter 10

Hong Kong (continued)

We were already surrounded by cargo junks and had started discharging cargo into them with our derricks (the photo below shows a cargo ship moored in Victoria Harbour surrounded by cargo junks and a couple of walla-wallas).

After getting my „mugshot“, I went up to the chart room to find out where we really were, our mooring position being marked on the chart and from the chart I gained a lot of useful landmark information about Kowloon and HK Island. I could see the Star ferries criss-crossing the harbour and spent a lot of time watching aircraft land and take-off from Kai Tak. Since I as far as work was concerned basically „redundant“ while in harbour but the mates and engineers still had to carry out their duties, if I didn‘t want to go „stir-crazy“ I would have to find out how to get ashore and how to get back again. The answer lay in „Walla-Wallas“.

A Walla-Walla, so named because of the noisy sound generated by its engine, was made of timber and had no deck. With a low driving power of around 10 to 20 horsepower, walla-wallas were mainly used to carry people across Victoria Harbour and convey seafarers of ocean-going vessels to the downtown piers. The length of each boat was capped at 20 feet (6 metres), and its maximum carrying capacity was 20 people. Being small in size, the walla-wallas could manoeuvre in the inner waters of Victoria Harbour easily. At their height, there were around 200 walla-wallas in Hong Kong waters in the 1960s. Walla-wallas also played an important role at night after ferry services had stopped. From around midnight to 6:30 a.m., people had to rely on the walla-wallas for crossing the harbour between Victoria and Tsim Sha Tsui or for seamen to get back aboard their ships after a „night out in town“, to put it mildly!

I took a Walla-Walla to the Star ferry Central terminal in Victoria.

The photo below taken in 1968 shows the new (at that time) Victoria Central dual-level Star ferry terminal which was built on landfill (sand coloured). This new terminal would in later years sucumb to yet more landfill but yet again a new Star terminal replacement would be built. The original landing terminal „Blake Pier“ can be seen jutting out above the landfill (note the old building just above the pier).

Below, a Star ferry approaching Blake Pier in the early 60‘s. Note the „old building“ mentioned previously.

Instead of leaving the terminal to „sight-see“ Victoria, I boarded a Star ferry bound for Tsim Sha Tsui in Kowloon. If I remember correctly it only took about 12 minutes to cross the harbour. Was it the opening scene of the movie „Suzie Wong“ that caused my fascination with the ferries or was it the Chinese passengers (especially the girls) aboard or the harbour views when crossing? As soon as we arrived at Kowloon I took the next ferry back across the harbour but this time to Wan Chai. I got off the ferry at Wan Chai and walked around the streets mesmerised. That was when I saw my first Hong Kong tram which, being myself from Glasgow, made me feel at home. I made a note to find out more about these trams and then finally returned to Wan Chai Star terminal and took the next ferry back to Kowloon. From Tsim Sha Tsui I took the ferry back to Victoria Central and, as the sun was going down, got a „Walla Walla“ to take me back „home“.

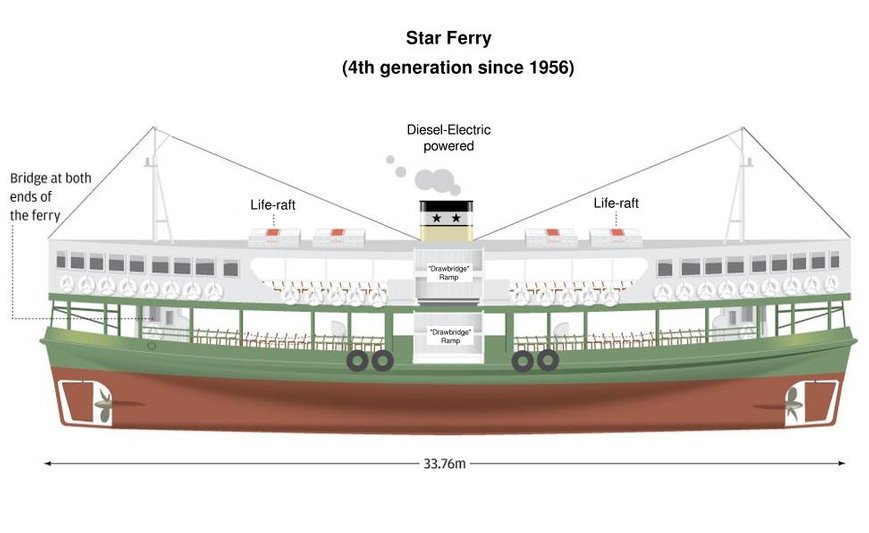

The diagram above shows the version of the majority of the Star ferries plying the harbour today, as in 1969. The vessel has two „passenger“ decks, the lower one for light cargo and passengers and the upper, more expensive, for passengers only. The upper level was later split into air-conditioned (shown with grey windows) and non-aircon zones.

Passengers boarded the vessel via two „drawbridge“ ramps which were lowered to the two tiers of the respective ferry terminal. The term „quick turn-around“ didn‘t apply to these vessels. In the 1960‘s before the harbour tunnel was built around 50 million passengers crossed the harbour aboard Star ferries each year. To avoid any „turn-around“ lost time (time is money) a vessel‘s engine was geared to one of two propellors and steered by one of two rudders. This is a bit of a seafarer‘s dilemna – where is „fore“ and where is „aft“?

For instance in the diagram above, assume that the vessel is going to leave the terminal from right to left. There are two command bridges aboard so in this case the coxswain will enter the bridge on the left and couple the main engine to the propellor on the right. The rudder just forward of him must be aligned and kept to the ship‘s head while he takes control of the rudder to the right.

To make matters even a bit more complicated, what about the „Port=Red“ and „Starboard=Green“ navigation lights – depending on direction these would also have to be „swapped“.

I have seen a number of Star ferries that have had radar installed however with only one radar antenna on one of their two masts. A radar system aboard a ship with only one antenna, one transceiver but with two operator radar consoles was nothing new but there was not a simple „switch-over“ procedure involved. To „switch-over“ from one console to another, the radar had to be totally „run-down“ and switched off. The radar would then be manually switched-over at an „interswitch“ unit to the other console and then re-started. I never was able to find out if the Star ferries could operate the radar from both bridges or, if in thick fog, would have to disengage the engine and ruder, run to the command bridge that had the radar console installed in, reengage the engine and rudder and then turn the ship around.

The next day I took a walla-walla across to Kowloon and „sightseed“ the peninsula. Nathan Road was a favourite amongst visiting seamen as this was where the bars with the hookers were to be found. After Thailand I was more interested in all the other fascinating things to be seen just about everywhere you looked. I made a note to visit Kai Tak airport in Kowloon Bay the next day but for today I wanted to get on a tram and to do so had to take the Star ferry across to Victoria Central.

There is hardly any other iconic transport form for which Hong Kong people feel so strongly about, except for the Star Ferries.

It is said that trams caused a sensation when they were first introduced over 100 years ago and people would flock to the tram lanes just to get a look at them. Trams were also obstructed by hawkers who would drag their heavy carts on the tram tracks, following which the authorities in 1911 passed a law, banning carts with the same wheel gauge as the trams. That law still applies today.

The trams are numbered up to 170, with certain numbers missing owing to local superstitions or accidents and they cover six routes (totalling 30km) along the north side of Hong Kong Island, providing service between Shau Kei Wan, Happy Valley and Kennedy Town from early morning to midnight.

Above, a view of Hong Kong trams in the 1960‘s

Trams and tramways were informally called the "Ding Ding" by the Chinese passengers in reference to the double-bell ring used by the trams to warn pedestrians of their approach.

In 1969 the average tram speed was around 30 kilometres per hour (19 mph) and there was no better way to view the sights of the northern Hong Kong waterfront. In 1969 when travelling with the tram you could view a lot of the harbour between the buildings but later when more and more landfill was used, the new buildings erected on the landfill blocked out the views.

I spent hours blissfuly cruising up and down the line mesmerized by all I saw around me. On the one side the mountains rising directly behind the buildings and on the other the harbour peeking through. I wasn‘t the only one who enjoyed the experience – as one Hong Kong woman explained: "Trams give some semblance of calm to the otherwise hectic Hong Kong life. Whenever I feel stressed, I board a tram, sit on the upper deck and relax, and watch the city pass by. They are the best way to explore Hong Kong, you can hear, see and smell what's happening around on the streets " (the trams are not air-conditioned and hence in summer time the windows are slid down).

Kai Tak Airport

Having watched aircraft landing and taking off from Kai Tak airport while we were moored in the harbour I just had to get up close to the action.

This was no ordinary airport as the landing strip was built on landfill in the Kowloon Bay. Aircraft could not make a direct approach to the runway from the land side because of the mountains which rose directly behind it. Landing from the bay side was a no-go because if an aircraft overshot the runway it would smash into the residential buildings at the end of it. Pilots landing at Kai Tak had to use all their skill to get the aircraft down safely. They did this generally in all kinds of weather too – Kai Tak was the international airport for Hong Kong - the only one for commercial flights.

Watching these aircraft maneuvering on their final approach and landing became almost addictive – is he going to make it?

At the northern end of the runway, buildings rose up to six storeys just across a major arterial road. The other three sides of the runway were surrounded by Victoria Harbour. The low-altitude turning manoeuvre before the shortened final approach was so spectacular that passengers could spot television sets in the apartments: "...as the plane banked sharply to the right for landing ... the people watching television in the nearby apartments seemed an unsettling arms length away."

Little did I know then that much later in the future I myself would experience the exact same thing when landing at Kai Tak (and taking off again after a transfer).

On my way to Kai Tak through the streets of Kowloon, aircraft were passing overhead one after the other almost scraping the rooftops on their final approach – the noise of their jet engines deafening.

As soon as one aircraft was rolling out near the end of the runway after landing, the next was already making its final approach.

Kowloon residents suffered this day-in, day-out. To give you an idea of just how close these aircraft flew above the buildings below, have a good look at this American Airlines jet:

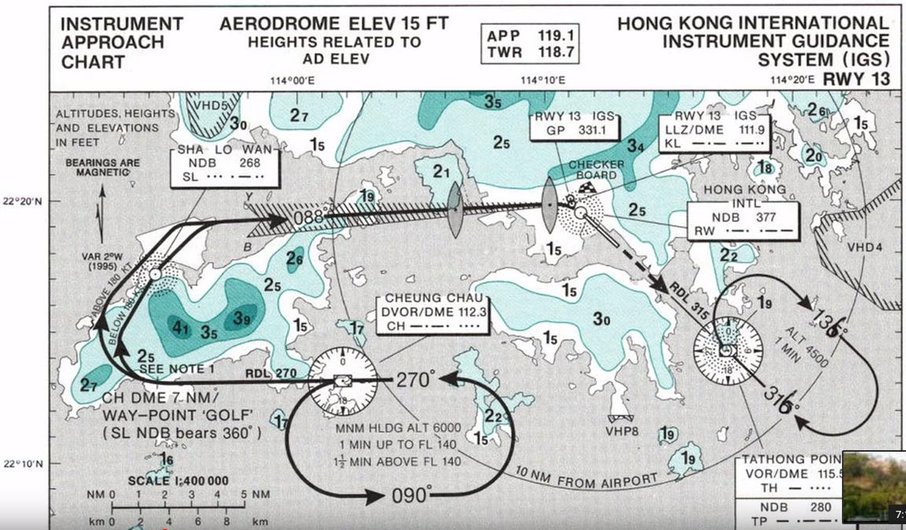

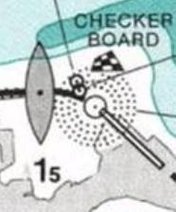

An Instrument Landing System (ILS) was installed in 1974 to aid landing. Part of this system was a red and white checkerboard painted on the side of a hill just north of the runway and on top of it was mounted the glideslope antenna and transmitter house.

The chart above shows the flight path an aircraft would take with the aid of Non Directional (Radio) Beacons (NDBs) and the IGS (ILS) beacons. The aircraft first flew westwards and then circled around Tai Yue Shan (Lantau Island) before heading down the ILS glideslope beam which guided it towards the Checkerboard.

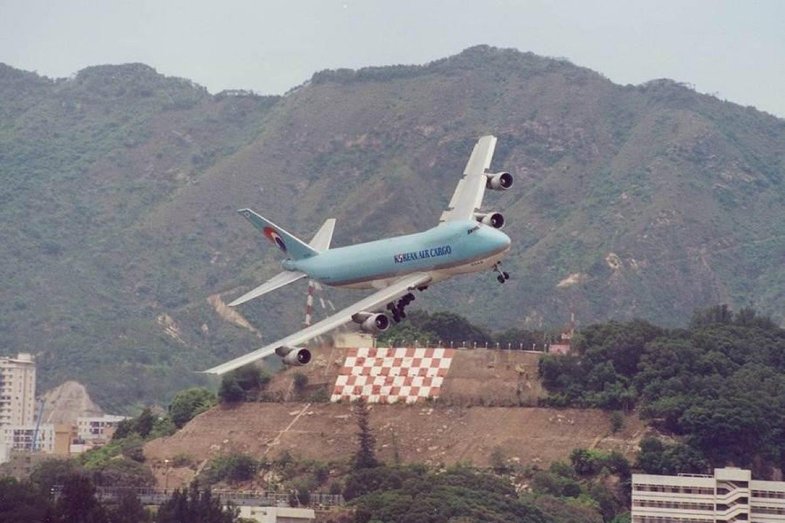

Upon reaching the small hill marked with the red and white checkerboard, used as a visual reference point on the final approach (in addition to the middle marker on the Instrument Guidance System), the pilot needed to make a 47° visual right turn to line up with the runway and complete the final leg. The aircraft would be just two nautical miles (3.7 km) from touchdown, at a height of less than 1,000 feet (300 m) when the turn was made. Typically the plane would enter the final right turn at a height of about 650 feet (200 m) and exit it at a height of 140 feet (43 m) to line up with the runway. This manoeuvre was called the “Hong Kong Turn” or “Checkerboard Turn”. Pilots had to undergo simulator training on landing/take-off from Kai Tak and make a landing or landings as co-pilot with an experienced „Kai-Tak“ pilot before he was certified to land himself.

Above, a KAL Jumbo making the „Checkerboard Turn“ - note the mountain in the background and below a Jumbo, still in its turn on descent.